Usher Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

2018 ICD-10 Code: H35.53: Other dystrophies primarily involving the sensory retina.

Disease

Usher syndrome, also known as Hallgren syndrome, is a rare genetic condition characterized by progressive vision and hearing loss. The syndrome was first described by von Graefe in 1858 and later named after British ophthalmologist Charles Usher, who further distinguished it as a separate entity from retinitis pigmentosa.

Usher syndrome has been classified into three major subtypes: I, II, and III.

While all three types involve progressive vision loss due to retinitis pigmentosa (RP), they are categorized according to the severity of their phenotypes as well as their associated genetic mutations.

Usher Syndrome Type I is the most severe subtype. It is characterized by profound congenital sensorineural hearing loss, early onset retinopathy, and absent vestibular function.

Usher Syndrome Type II is less severe. Patients with this subtype have moderate-to-severe congenital, non-progressive hearing loss, adult onset retinopathy, and normal vestibular function.

Usher Syndrome Type III involves progressive hearing loss and retinopathy, and varying degrees of vestibular dysfunction. The onset for type III is typically within the second to fourth decades of life. These patients also tend to have better vision than the other subtypes.[1]

Genetics

Usher syndrome follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. To date, 13 genes and 16 loci have been identified as contributors to the disorder.[2]

Usher Syndrome I Genes: CDH23, MYO7A, PCDH15, USH1C, CIB2 and USH1G

Usher Syndrome II Genes: USH2A, GPR8, and DFNB31.

Usher Syndrome III Genes: CLRN1 and PDZD7

Usher Syndrome I Loci: USH1B, USH1C, USH1D, USH1E, USH1F, USH1G, USH1H, USH1J, USH1K

Usher Syndrome II Loci: USH2A, USH2C, USH2D

Usher Syndrome III Loci: USH3A

In general, genes associated with Usher syndrome provide instructions for the synthesis of proteins involved in normal hearing, balance, and vision.[3]

Epidemiology

Usher syndrome is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 3 cases per 100,000 individuals.[4] However, it is more common among genetically deaf individuals, accounting for 5-10% of cases.[5] In the United States, the estimated incidence is approximately 1 in 23,000 people.[6]

Type I is more prevalent among individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish or French Acadian descent.[7][8] Type II is the most common, making up two-thirds of all cases. Type III is the rarest, accounting for only 2% of cases and is more frequent in Finnish populations.[9]

Pathophysiology

The progressive vision loss in Usher syndrome is attributed to retinitis pigmentosa (RP), which leads to the degeneration of photoreceptor cells in the retina. At the junction of the inner and outer segments are connecting cilium and the periciliary ridge region, which form the periciliary membrane complex (PMC). This complex serves an essential role as a diffusion barrier controlling transport to the outer segment.

Mutations in Usher syndrome type I genes—including MYO7A, harmonin, cadherin-23, protocadherin-15, and sans—disrupt the organization and function of the PMC, leading to progressive retinal degeneration.[10] Similarly, mutations in Usher syndrome type II genes—such as usherin, ADGRV1 (GPR98), and whirlin—interfere with the structural integrity and stability of the PMC, further contributing to retinal dysfunction. Additionally, mutations in the MYO7A gene, which encodes for myosin VIIA, result in defects in the transport of melanosomes and visual pigments within the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This disruption impairs visual pigment regeneration, ultimately accelerating photoreceptor cell death. Mutations in USH1C, which encodes for the harmonin protein, cause abnormal splicing, leading to improper protein function and contributing to retinal degeneration over time.[2]

Hearing loss in Usher syndrome is due to defects in the inner ear hair cells, which are responsible for transmitting sound vibrations and auditory signals to the brain. The stereocilia of these hair cells rely on a network of Usher proteins to maintain their structural integrity and function. Mutations in USH genes disrupt the formation and stability of these stereocilia bundles, leading to hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction. Additionally, these genetic mutations impair neural transmission from the hair cells to the auditory nerve, further contributing to progressive hearing decline. In individuals with Usher syndrome type I, these defects result in profound congenital deafness, whereas in Usher syndrome type II and III, the hearing loss is milder or progresses over time.[2]

Diagnosis

At present, Usher syndrome is incurable. However early diagnosis allows for interventions such as cochlear implantation, which can profoundly improve development of language and other communication milestones.

Genetic Testing: Definitive diagnosis of Usher Syndrome type 1 involves identifying a homozygous proband mutation in the setting of positive symptoms and family history. The first gene to identify using single-gene sequencing is MYO7A. Only if a MYO7A mutation is absent or present in one gene should gene targeted deletion/duplication for MYO7A be done. Multigene panel is also an option for identifying mutations in the other genes mentioned in the genetics section. If single-gene or multigene testing fails to show mutations, a comprehensive genomic testing may be used to identify a mutation.[11]

Acadian patients should be tested for p.Val72Glu in USH1C and Ashkenazi Jewish patients should be tested for p.Arg245Ter in PCDH15 if suspicious for Usher syndrome.[11]

Audiology: to assess for abnormal hearing loss and severity.[11]

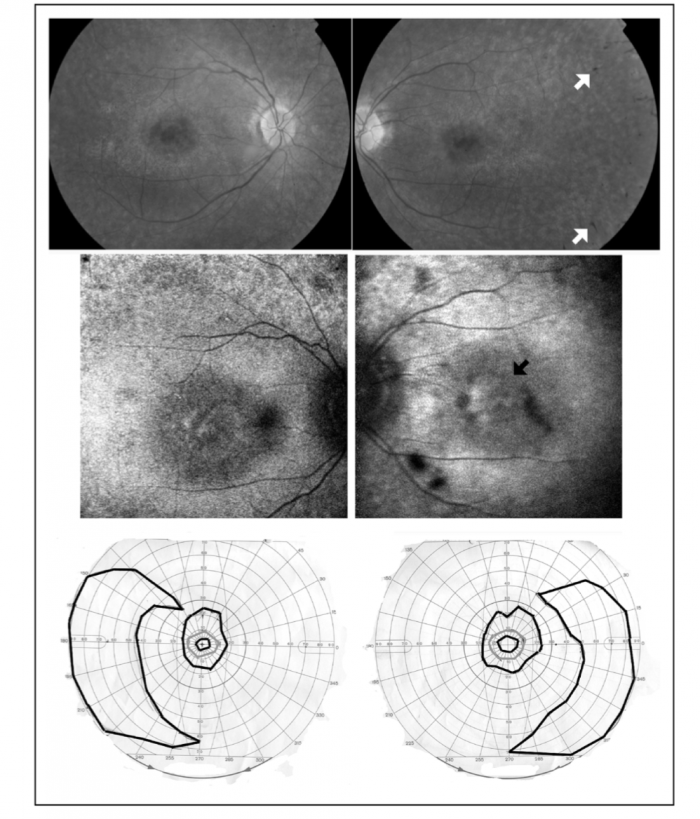

Electroretinography Erg: to assess retinal function.[11]

Ophthalmoscopic examination: to identify signs of retinitis pigmentosa.[11]

Visual Field Testing: to identify abnormal visual field defects.[11]

Clinical Presentation

Usher Syndrome Type I: Patients are born profoundly deaf, resulting in severe speech impediment and language delay, and lose visual acuity within the first decade of life. By the age of 15 years, many will report nyctalopia, and symptoms can gradually progress to severe visual field loss and blindness.[13] Due to absent vestibular dysfunction, patients exhibit balance difficulty with delays in motor development, often failing to walk before the age of 18 months.[14]

Usher Syndrome II: In contrast to Type I, patient with Usher Syndrome II do not have congenital deafness. Rather, they have moderate-to-severe hearing loss that does not degrade over time. Furthermore, these patients do not exhibit any difficulty with balance. Onset of visual loss in these patients is in the second decade of life. These patients may also have preserved visual acuity into the third and fourth decades of life.[2]

Usher Syndrome III: Similar to Type II, patients with Usher Syndrome III do not have congenital deafness. Instead they experience progressive hearing loss. Vision loss is also variable in progression with onset that tends to begin in the second decade of life. Additionally, they exhibit varying degrees of balance issues due to mild to moderate vestibular dysfunction.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

- Nonsyndromic Hearing Loss

- Deafness-Dystonia-Optic Neuronopathy Syndrome

- Alport Syndrome

- Bardet--Biedl Syndrome

- Alstrom syndrome

- Cockayne Syndrome

- Friedreich Ataxia

- Hurler Syndrome

- Kearns-Sayre Syndrome

- Rubella retinopathy

- Syphilis retinopathy

- Refsum disease (Zellweger spectrum)

- Alström disease

- Flynn-Aird syndrome

- Jeune syndrome

- Joubert syndrome

- Senior-Loken syndrome

Management

Even though much progress has been made in elucidating the genetics and pathophysiology of Usher syndrome, there is still no cure. Treatment focuses on managing the auditory, balance, and visual manifestations, and improving quality of life.

Initial Diagnosis: The following evaluation modalities may be useful to establish the extent of the disease[11]:

- Audiology: Otoscopy, Pure tone audiometry, assessment of speech perception

- Vestibular Function: Rotary chair, calorics, electronystagmography, and computerized posturography

- Ophthalmology: Fundoscopy, visual acuity, visual field (Goldmann perimetry), and electroretinography

- Clinical Genetics: Clinical geneticist consultation

Treatment of Auditory Manifestations: Hearing aids provide limited benefit in patients with Usher I due to the severity of hearing loss, but can be helpful in patients with Usher II and III. Cochlear implants should be seriously considered in patients of all types.[15] Consider specialized training from educators of the hearing impaired.

Treatment of Vestibular Manifestations: Combination of RP which manifests as tunnel vision and night blindness with vestibular dysfunction predisposes patients to accidental injury. It is recommended that patients participate in well-supervised sports activities to compensate for balance problems by becoming more adept at somatosensation.[11]

Treatment of Visual Manifestations: Visual problems result from RP, which is currently incurable. Treatment is focused on correcting refractive error, treating cataract, and monitoring for associated retinal complications such as macular edema. The incidence of cystoid macular edema in Usher patients varies from 8-60% in reported studies.[16][17][18] Prompt referral to low vision and access to low vision aides. Various supplements such as Vitamin A, DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), and Lutein may be helpful in delaying disease progression, but the literature is equivocal on efficacy.[19] Vitamin A supplementation is a controversial treatment that has since lost favor due to the lack of clinical perceivable improvement by patients and risk of adverse events especially in large doses.[20] More promisingly, a group led by Johns Hopkins is also evaluating the role of N-acetylcysteine (NAC), an oral antioxidant currently used in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose and pulmonary conditions.[21]

Gene Therapy: Recent advances in gene therapy have led to the development of numerous trials targeting genes of interest.[22][23] AAVantgarde Bio is currently conducting a phase 1/2 trial for treatment of USH1B caused by the gene MYO7A with sites in Italy and the UK, and plans to expand to the US during phase 3. The gene therapy, called AAVB-081, delivers healthy copies of the MYO7A gene subretinally via an adeno-associated virus vector.[24] Théa is developing RNA therapies via an intravitreal injection of an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) to induce skipping of exon 13 in USH2A. This requires patients to have a pathogenic exon 13 mutation in the USH2A gene to participate. [25] Additionally, an oral drug, called BF844, is being studied in Australia for treatment of USH3.[26]

Surveillance: It is recommended that patients have routine ophthalmologic evaluation to detect possible complications of the disease process such as cataracts. The Foundation Fighting Blindness is also funding two studies that studies the natural history of people with mutations in USH2A, and PCDH15.[23]

Genetic Counseling: Genetic evaluation is recommended for family members to determine genetic risk, carrier status, and to determine eligibility in clinical trials.

Prognosis

Usher I and II have congenital onset of hearing loss and early identification with Cochlear implantation can often aid language development. Because of the gradual progression of hearing loss in Usher Syndrome Type III hearing aids are often used successfully. Usher types I, II, and III have progressive loss of visual acuity by midlife. In one study, the percentage of patients maintaining visual acuity of 20/40 or better by age 29 was 68% for Usher Syndrome type 1, and 94% type 2.[27]

Conclusion

Usher syndrome is a rare genetic condition that leads to various degrees of hearing and vision loss over time. It is classified into three subtypes (I, II, and III) according to onset and severity of symptoms. Type II is the most common and does not have vestibular dysfunction. While currently incurable, advancements in gene therapy and assistive technologies offer hope for future treatments.[28]

Additional Resources

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Usher syndrome. The Genetic and Rare Diseases (GARD) Information Center. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7843/usher-syndrome/ Accessed 09 December 2019.

- Porter D, Vemulakonda GA. Usher Syndrome. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/usher-syndrome-list. Accessed December 09, 2019.

References

- ↑ Friedman TB, Schultz JM, Ahmed ZM, Tsilou ET, Brewer CC. Usher syndrome: hearing loss with vision loss. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;70:56-65.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Mathur P, Yang J. Usher syndrome: Hearing loss, retinal degeneration and associated abnormalities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(3):406-20.

- ↑ Millán JM, Aller E, Jaijo T, Blanco-kelly F, Gimenez-pardo A, Ayuso C. An update on the genetics of usher syndrome. J Ophthalmol. 2011;2011:417217.

- ↑ Kimberling WJ, Hildebrand MS, Shearer AE, et al. Frequency of Usher syndrome in two pediatric populations: Implications for genetic screening of deaf and hard of hearing children. Genet Med. 2010;12(8):512-6.

- ↑ Vernon M. Usher's syndrome--deafness and progressive blindness. Clinical cases, prevention, theory and literature survey. J Chronic Dis. 1969;22(3):133-51.

- ↑ Boughman JA, Vernon M, Shaver KA. Usher syndrome: definition and estimate of prevalence from two high-risk populations. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36(8):595-603.

- ↑ Ben-yosef T, Ness SL, Madeo AC, et al. A mutation of PCDH15 among Ashkenazi Jews with the type 1 Usher syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1664-70.

- ↑ Ebermann I, Koenekoop RK, Lopez I, Bou-khzam L, Pigeon R, Bolz HJ. An USH2A founder mutation is the major cause of Usher syndrome type 2 in Canadians of French origin and confirms common roots of Quebecois and Acadians. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(1):80-4.

- ↑ NIH. Usher Syndrome. Genetics Home Reference. July 9, 2019.

- ↑ Delmaghani S, El-Amraoui A. The genetic and phenotypic landscapes of Usher syndrome: from disease mechanisms to a new classification. Hum Genet. 2022 Apr;141(3-4):709-735. doi: 10.1007/s00439-022-02448-7. Epub 2022 Mar 30. PMID: 35353227; PMCID: PMC9034986.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Lentz J, Keats B, Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, Bird TD, Ledbetter N, Mefford HC, Smith RJH, Stephens K. Usher Syndrome Type I, Usher Syndrome Type II. GeneReviews®. 1999 Dec 10 [updated 2016 Jul 21].

- ↑ Saihan Z, Webster AR, Luxon L, Bitner-glindzicz M. Update on Usher syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(1):19-27.

- ↑ Fishman GA, Kumar A, Joseph ME, et al. Usher’s syndrome: ophthalmic and neuro-otologic fndings suggesting genetic heterogeneity. Arch Ophthalmol 1983;101(9):1367–74.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Mets MB, Young NM, Pass A, Lasky JB. Early diagnosis of Usher syndrome in children. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:237-42.

- ↑ Damon, G., Pennings, R., Snik, A., & Mylanus, E. (2006). Quality of life and cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome type I. Laryngoscope, 116, 723–728

- ↑ Walia S, Fishman GA, Hajali M. Prevalence of cystic macular lesions in patients with Usher II syndrome. Eye (Lond) 2009;23(5): 1206–9.

- ↑ Tsilou ET, Rubin BI, Caruso RC, et al. Usher syndrome clinical types I and II: could ocular symptoms and signs differentiate between the two types? Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2002;80(2):196–201.

- ↑ Schwartz SB, Aleman TS, Cideciyan AV, et al. Disease expression in Usher syndrome caused by VLGR1 gene mutation (USH2C) and comparison with USH

- ↑ Berson EL, Rosner B, Sandberg MA, et al: A randomized trial of vitamin A and vitamin E supplementation for retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993; 111(6):761-772.

- ↑ Comander J, Weigel DiFranco C, Sanderson K, et al. Natural history of retinitis pigmentosa based on genotype, vitamin A/E supplementation, and an electroretinogram biomarker. JCI Insight. 2023;8(15):e167546. Published 2023 Aug 8. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.167546

- ↑ Fighting Blindness. Phase 3 clinical trial of NAC launched for RP patients. Fighting Blindness. Published March 7, 2024. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.fightingblindness.org/news/phase-3-clinical-trial-of-nac-launched-for-rp-patients-623.

- ↑ Toms M, Pagarkar W, Moosajee M. Usher syndrome: clinical features, molecular genetics and advancing therapeutics. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2020 Sep 17;12:2515841420952194. doi: 10.1177/2515841420952194. PMID: 32995707; PMCID: PMC7502997.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Fighting Blindness. Usher syndrome research advances. Fighting Blindness. Published March 5, 2024. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.fightingblindness.org/news/usher-syndrome-research-advances-690.

- ↑ AAVantgarde Bio Srl. Study of subretinally injected AAVB-081 in patients with Usher syndrome type IB (USH1B) retinitis pigmentosa. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06591793. Updated September 19, 2024. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06591793.

- ↑ Laboratoires Thea. Study to evaluate Ultevursen in subjects with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) due to mutations in exon 13 of the USH2A gene (LUNA). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06627179. Updated March 11, 2025. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06627179.

- ↑ EyeXCel Pty. Ltd. BF844 safety and pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06592131. Updated September 19, 2024. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06592131.

- ↑ Piazza L, Fishman GA, Farber M, Derlacki D, Anderson RJ. Visual Acuity Loss in Patients With Usher's Syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104(9):1336–1339. doi:10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210090031

- ↑ Aparisi MJ, Aller E, Fuster-garcía C, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing for molecular diagnosis of Usher syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:168.