Retinal Artery Occlusion

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

A symptomatic retinal artery occlusion is an ophthalmic emergency that requires immediate evaluation and transfer to a stroke center. It is an obstruction of retinal blood flow that may result from an embolus causing occlusion or thrombus formation, vasculitis causing retinal vasculature inflammation, traumatic vessel wall damage, or spasm. The lack of oxygen delivery to the retina during the blockage often results in severe vision loss in the area of ischemic retina. Patients often have concurrent silent ischemic stroke.[1] No evidence-based treatments have yet been demonstrated to have visual benefit, and a 2015 meta-analysis of fibrinolysis suggests that many interventions may be harmful or even fatal.[2]

Disease

Etiology

Retinal artery occlusion may occur in any of the vessels supplying the eye. The main artery that supplies the eye and surrounding structures is the ophthalmic artery. The central retinal artery, the first branch of the ophthalmic artery, is the main blood supplier of the inner layers of the retina. After entering the eye, the central retinal artery divides into superior and inferior branches. In addition, the cilioretinal artery is a branch of the short posterior ciliary arteries, which is a separate branch of the ophthalmic artery. This artery supplies the choroid and the outer retinal layers.

The blood flow through any of these vessels may be disrupted during a retinal artery occlusion. Blockage may be caused by emboli, vasculitis, or spasms. Occlusion of the ophthalmic artery and the cilioretinal artery is often due to giant cell arteritis. Occlusion of the cilioretinal artery may also be secondary to a central retinal vein occlusion, due to increased outflow resistance.

Risk Factors

The risk factors and demographics of retinal artery occlusion are similar to those of ischemic stroke and include several modifiable risk factors:

- Older age

- Male gender

- Smoking

- Hypertension

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Hyperlipidemia

- Cardiovascular disease

- Coagulopathy

General Pathology

Obstruction of the retinal vascular lumen occurs due to an embolus, thrombus, or inflammatory/ traumatic vessel wall damage or spasm. Giant cell arteritis may also be associated with this condition.

Pathophysiology

The central retinal artery supplies the inner retina. Occlusion of the retinal arteries results in ischemia of the inner retina. When the inner retina is damaged, it first becomes very edematous. Over time, the edema resolves and the inner retina atrophies. In central retinal artery occlusion, the outer retina is perfused by the choroidal circulation and some inner retina tissue may survive, thus some vision is preserved. Over the course of about 1 week, the occlusion may recannulate. Unfortunately, the retina is very sensitive to ischemia and animal models have demonstrated that irreparable damage occurs after 105 minutes of occlusion.[3][4] In rare cases of complete central retinal artery occlusion, it has been suggested that irreversible retinal ganglion cell death can occur within 12–15 minutes.[5] Thus, the vision loss is often permanent, with only mild visual recovery.

In branch retinal artery occlusion, only part of the retina is involved. The area of retina affected by the occluded vessels is associated with the area and degree of visual loss.

In contrast, ophthalmic artery occlusion causes ischemia of both the inner and outer retina. This produces very severe loss of vision, often resulting in no light perception.

Primary Prevention

Control of modifiable risk factors is the primary prevention of this disorder. These modifiable risk factors should be aggressively managed in patients who have experienced vision loss in 1 eye. Ideally, this should be done in conjunction with a stroke/neurology service.

The most important risk factor to manage is giant cell arteritis. Patients who are suspected to have ophthalmic artery occlusion secondary to giant cell arteritis should be started immediately on corticosteroids and continue to take the medication for 6 to 12 months. A temporal artery biopsy should be performed within 2 weeks of initiating steroids to increase chances of positive biopsy, although some authors have noted positive biopsy results even 4 weeks after steroid initiation.[6] A new agent, tocilizumab, may reduce the amount of time that patients need to be treated with corticosteroids. Giant cell arteritis has only been reported in persons over 50 years of age.

Diagnosis

History

Patients typically describe sudden, painless, vision loss that occurs over seconds. Visual acuity may vary depending on the location of the obstruction. Complete vision loss to no light perception should raise suspicion of an ophthalmic artery occlusion. Patients with central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) complain of visual loss over the entire field of vision, while those with a branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) complain of hemifield defect. A patient with cilioretinal artery sparing may have 20/20 vision. Visual loss may have been preceded by transient loss of vision in the past (amaurosis fugax) in the case of embolic sources.

Sudden vision loss in a patient older than 50 years of age should immediately raise suspicion for Giant Cell Arteritis. Systemic steroids may be urgently needed to preserve vision in the affected eye and prevent vision loss in the unaffected eye (PPP strong recommendation).[7] Diabetic patients may need close follow-up, as steroids will cause hyperglycemia.

Systemic evaluation for vascular occlusive disease is needed. In young patients, a vasculitis and/or hypercoagulable workup should be performed. In older patients, an embolic workup should be performed. (PPP strong recommendation).[7] Emergent stroke workup is recommended for acute CRAOs.

Physical examination and signs

A relative afferent pupillary defect may be present in central retinal artery occlusion or ophthalmic artery occlusion.

Early in the course, the fundus may appear normal.

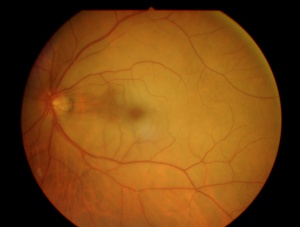

In central retinal artery occlusion, the classic findings of retinal whitening and a cherry red spot are due to opacification of the nerve fiber layer as it becomes edematous from ischemia. The fovea is cherry red because it has no overlying nerve fiber layer. This finding may take hours to develop, and the edema is associated with a worse visual prognosis. Over the course of about a month, the inner retina becomes atrophic as the swelling resolves.

Examination of the retinal blood vessels shows segmental blood flow, classically described as boxcarring. This is best appreciated with slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Over about the course of a week, the vessels reperfuse.

Chronic signs of retinal artery occlusion include pale optic disc, thinned retinal tissue, attenuated vessels, retinal pigment epithelial mottling, and severely decreased vision. In the case of BRAOs, there may be artery-to-artery anastomoses.

Clinical diagnosis

Acutely, diagnosis is prompted by the sudden onset of visual acuity loss and the presence of retinal whitening. There is a corresponding field defect. The affected blood vessel shows sluggish blood flow (boxcarring of the blood column). There may be a refractile lesion within the blood vessel (Hollenhorst plaque [cholesterol]), a whitish lesion within a section of the blood vessel usually at branching (platelet-fibrin) or large calcific plaque (cardiac valvular disease). The arteries are attenuated. Veins may be attenuated, slightly dilated, or normal.

Diagnostic procedures

Optical coherence tomography reveals hyperreflectivity and edema of the inner retinal layers in acute stages. The amount of retinal edema is related to the visual prognosis.[8] Over the course of about 1 month, the inner retinal layer becomes atrophic.

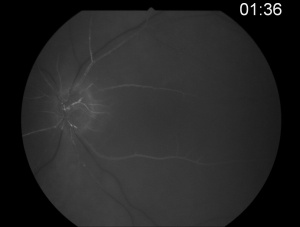

Fluorescein angiography shows a delay in the filling of the retinal arteries and a delayed arteriovenous transit time in the affected areas. The flow of blood in retinal arteries is very sluggish. The front edge of fluorescein (an arterial dye front-the angiographic feature with highest specificity) is seen to travel very slowly to the peripheral retina along the branches of retinal arteries. Complete lack of filling of the retinal vessels is very rare. Delayed choroidal filling should point to an ophthalmic or carotid artery obstruction. Over time, the vessels recanalize and flow reverts to normal, despite the persistence of retinal vessel narrowing. When retinal circulation re-establishes, the retinal fluorescein angiogram may be unremarkable, despite clinically pale retina, and cherry red spot, especially in cases where no emboli or boxcarring is clinically visible.

Poor perfusion of the arterial tree can be demonstrated by the ability to induce retinal pulsations in the central retinal artery by slight digital pressure on the eyeball (ophthalmodynamometry).

Electroretinography (ERG) shows a characteristic diminution of the b-wave. This is due to inner retinal ischemia. The ERG may be normal in some cases (despite poor visual acuity) if the blood flow renormalizes.

Laboratory test

An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and complete blood cell (CBC) count with platelets should be obtained in patients over the age of 50 who have symptoms of giant cell arteritis (PPP strong recommendation).[7]

Patients younger than 50 years should have a hypercoagulability workup including antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, autoimmune conditions, inflammatory disorders, and other hypercoagulable states (PPP strong recommendation).[7] In a young patient with multiple or recurrent BRAOs, Susac syndrome should be considered.

In older individuals, atherosclerosis and emboli are the most likely causes of the ischemia. Evaluation of the heart with echocardiography should be performed to determine cardiac function and abnormalities of the valves. Electrocardiograms and heart monitoring may reveal a rhythm defect. Carotid artery stenosis should be evaluated with carotid ultrasound (PPP strong recommendation).[7]

Differential diagnosis

Branch retinal artery occlusion: Sectoral whitening in the path of a branch retinal artery is pathognomonic for a BRAO.

Central retinal artery occlusion has retinal artery boxcarring and whitening in all 4 quadrants, with vision usually between 20/200 and hand motion.

Ophthalmic artery occlusion has both retinal artery findings and choroidal vascular nonperfusion. Vision is often no light perception. There is no cherry-red spot, as the choroidal perfusion is also occluded.

Carbon monoxide poisoning may also present with a cherry-red spot.

Ocular ischemic syndrome may present with transient symptoms of vision loss. There may be conjunctival injection and neovascularization of the anterior and posterior segments, with inflammation in the anterior chamber or vitritis. Optic nerve edema, cataract, and midperipheral retinal hemorrhages are often seen as well. Carotid disease is the most common cause.

Management

General treatment

Acute symptomatic retinal artery occlusion should prompt immediate emergent referral to the nearest stroke center. However, the evidence is limited for asymptomatic BRAO. (PPP strong recommendation)[7]

Medical therapy and follow-up

Retinal artery occlusion is an emergency that requires emergent systemic evaluation for cerebral vascular accident (CVA). Patients with acute CRAO, BRAO, and amaurosis fugax should be referred to the nearest stroke center for further immediate management.[9][10]

There are no evidence-based therapies that have demonstrated efficacy in improving visual outcomes, and a meta-study has suggested that some therapies may be worse than the natural course.[2] Some of these are described below.

Clot-busting tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was evaluated in the EAGLE study, which was a randomized controlled trial comparing intra-arterial fibrinolysis to placebo. The study did not recommend intra-arterial tPA for acute CRAO, because there was significant symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage without evidence of visual benefit.[11] The trial was terminated early due to the adverse effects of tPA.

A randomized controlled trial comparing intravenous tPA to placebo did show improved short-term visual benefit when given within 6 hours, but this was not sustained. [12] There was no long-term visual benefit, and intracranial hemorrhage was an adverse reaction noted in this small study. Although recent meta-analysis of observation studies suggests that there may be mild benefit to intravenous tPA when given within 4.5 hours, they also reported several fatalities associated with tPA.[2] Their analysis also suggested that conservative treatments (ocular massage, paracentesis, hemodilution) led to worse outcomes.[2]

Ocular massage is a conservative therapy that may theoretically cause emboli to travel more distally to reduce the area of ischemia. A 3-mirror contact lens is placed on the eye and pressure is applied for 10 s, to obtain retinal artery pulsation or flow cessation, followed by a 5 s release.[13] Similarly, anterior chamber paracentesis may be performed by removing 0.1-0.4 mL of aqueous fluid from the anterior chamber using a small-gauge needle (27 or 30 gauge).[14] Theoretically, the paracentesis lowers the intraocular pressure and may allow the embolus (if any) to move further down the vessel and away from the central retina. In addition, the intraocular pressure may be decreased medically with eyedrops.

Increasing carbon dioxide concentration has also been proposed to induce vasodilation. The patient is instructed to breathe into a bag in order to increase carbon dioxide concentration.[15] Alternatively, a patient may be given an oxygen mask to try to increase oxygen perfusion through the choroidal circulation. A mixture of 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide has also been proposed to increase blood flow.

Recent studies have shown a high risk of cerebrovascular event in the ensuing days, weeks and months after retinal artery occlusions. [9] For acute occlusions, the patient should be referred to the emergency department for immediate stroke workup. Patients should follow up with their primary care physicians for further workup. History of hypertension, nonstroke cerebrovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, and smoking in a patient with RAO increases the risk of stroke. [9]

Complications

Neovascularization of the iris, retina, or angle is an uncommon complication after central retinal artery occlusion.

Complications from invasive intervention with intravenous or intra-arterial tPA may include symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, choroidal hemorrhage, or death.[2] This treatment is controversial.

Prognosis

Visual loss with CRAO is usually severe and is strongly correlated with the amount of retinal edema present.[8] However, with CRAOs in the presence of a cilioretinal artery, visual acuity usually recovers to 20/50 or better in over 80 % of eyes.[16] Retinal neovascularization is uncommon, but it may occur, and patients should be followed closely.[17][18] [19]

Visual field loss in BRAOs is usually permanent. Visual acuity may recover to 20/40 or better in 80% of eyes, depending on the location of the occlusion.

Additional Resources

- AAO PPP Retina/Vitreous Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. AAO Retinal and Ophthalmic Artery Occlusions PPP - 2019. Preferred Practice Patterns. AAO Retinal and Ophthalmic Artery Occlusions PPP - 2019. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed December 03, 2024.

- Porter D, Vemulakonda GA. Retinal Artery Occlusion. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/stroke-affecting-eye. Accessed July 2, 2025.

American Academy of Ophthalmology CME Resources

- AAO Focal Points. AAO 2010 Focal Points: Retinal Artery Occlusions. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed December 03, 2024.

References

- ↑ Lee J, Kim SW, Lee SC, Kwon OW, Kim YD, Byeon SH. Co-occurrence of Acute Retinal Artery Occlusion and Acute Ischemic Stroke: Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jun 1;157(6):1231–8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Schrag, M., Youn, T., Schindler, J., Kirshner, H. & Greer, D. Intravenous Fibrinolytic Therapy in Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: A Patient-Level Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 72, 1148–1154 (2015).

- ↑ Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB, Kimura A, Sanon A. Central retinal artery occlusion. Retinal survival time. Exp Eye Res. 2004 Mar;78(3):723–36.

- ↑ Hayreh SS, Kolder HE, Weingeist TA. Central retinal artery occlusion and retinal tolerance time. Ophthalmology. 1980; 87:75-78.

- ↑ Tobalem S, Schutz JS, Chronopoulos A. Central retinal artery occlusion - rethinking retinal survival time. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018 Apr 18;18(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0768-4. PMID: 29669523; PMCID: PMC5907384.

- ↑ Ray-Chaudhuri N, Kiné DA, Tijani SO, Parums DV, Cartlidge N, Strong NP, et al. Effect of prior steroid treatment on temporal artery biopsy findings in giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002 May 1;86(5):530–2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Retinal and Ophthalmic Artery Occlusions PPP 2024 - American Academy of Ophthalmology

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ahn SJ, Woo SJ, Park KH, Jung C, Hong J-H, Han M-K. Retinal and choroidal changes and visual outcome in central retinal artery occlusion: an optical coherence tomography study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Apr 1;159(4):667–676.e1.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Shaikh IS, Elsamna ST, Zarbin MA, Bhagat N. Assessing the risk of stroke development following retinal artery occlusion. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020 Sep;29(9):105002. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105002. Epub 2020 Jun 15. PMID: 32807420.

- ↑ Chen TY, Uppuluri A, Aftab O, Zarbin M, Agi N, Bhagat N. Risk factors for ischemic cerebral stroke in patients with acute amaurosis fugax. Can J Ophthalmol. 2022 Nov 8:S0008-4182(22)00323-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2022.10.010. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36368408.

- ↑ Schumacher, M. et al. Central retinal artery occlusion: local intra-arterial fibrinolysis versus conservative treatment, a multicenter randomized trial. Ophthalmology 117:1367–1375.e1 (2010).

- ↑ Chen, C. S. et al. Efficacy of intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator in central retinal artery occlusion: report from a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 42, 2229–2234 (2011).

- ↑ Cugati S, Varma DD, Chen CS, Lee AW. Treatment options for central retinal artery occlusion Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013 Feb;15(1):63–77.

- ↑ Atebara NH, Brown GC, Cater J. Efficacy of anterior chamber paracentesis and Carbogen in treating nonarteritic central retinal arterial occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1995 Dec;102(12):2029-34; discussion 2034-5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30758-0. PMID: 9098313..

- ↑ Frayser R, Hickham JB. Retinal vascular response to breathing increased carbon dioxide and oxygen concentrations. Invest Ophthalmol. 1964;3:427-431.

- ↑ Brown GC, Shields JA. Cilioretinal arteries and retinal arterial occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(1):84-92.

- ↑ Duker JS, Brown GC. Neovascularization of the optic disc associated with obstruction of the central retinal artery. Ophthalmology. 1989; 96:87-91.

- ↑ Hayreh SS, Podhajsky P. Ocular neovascularization with retinal vascular occlusion, II. Occurrence in central and branch retinal artery occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:1585-96.

- ↑ Rudkin AK, Lee AW, Chen CS. Ocular neovascularization following central retinal artery occlusion: prevalence and timing of onset. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010 Nov-Dec;20(6):1042-6. doi: 10.1177/112067211002000603. PMID: 20544682.