Reflexes and the Eye

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Background

Reflexes are involuntary responses that are usually associated with protective or regulatory functions.[1] They require a receptor, afferent neuron, efferent neuron, and effector to achieve a desired effect.[1] In this article, we will cover a variety of reflexes involving the eye and their ophthalmologic considerations.

Pupillary Light Reflex

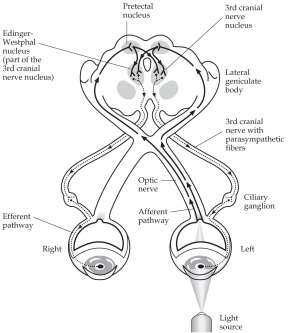

An autonomic reflex that constricts the pupil in response to light adjusting the amount of light that reaches the retina.[2] Pupillary constriction occurs via innervation of the iris sphincter muscle, which is controlled by the parasympathetic system.[2] In other words, this is a response communication between cranial nerve II and cranial nerve III in both sides.

Pathway

Afferent pupillary fibers start at the retinal ganglion cell layer and then travel through the optic nerve, optic chiasm, and optic tract, join the brachium of the superior colliculus, and finally end at the pretectal area of the midbrain, which sends fibers bilaterally to the efferent Edinger-Westphal (E-W) nuclei of the oculomotor complex.[2] From the E-W nucleus, efferent pupillary parasympathetic preganglionic fibers travel on the oculomotor nerve to synapse in the ciliary ganglion, sending parasympathetic postganglionic axons in the short ciliary nerve to innervate the iris sphincter smooth muscle via M3 muscarinic receptors.[1][2] Due to innervation of the bilateral E-W nuclei, a direct and consensual pupillary response is produced.[2]

Ophthalmologic Considerations

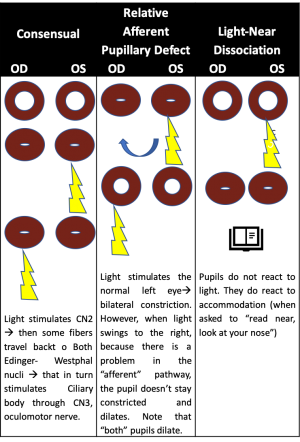

Testing of the pupillary light reflex is useful for identifying a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) caused by asymmetric afferent output from a lesion anywhere along the afferent pupillary pathway as described above.[1] In patients with an RAPD, when light is shined in the affected eye, there will be dilation of both pupils due to an abnormal afferent arm.[3] When the examiner swings the light to the unaffected eye, both pupils constrict. Detection of an RAPD requires both eyes but only one functioning pupil; if the second pupil is unable to constrict, perhaps due to a third nerve palsy, a “reverse RAPD” test can be performed using the swinging flashlight test.[4] Direct and consensual responses should be compared in the reactive pupil. If the reactive pupil constricts more with the direct response than with the consensual response, then the RAPD is in the unreactive pupil. Alternatively, if the reactive pupil constricts more with the consensual response than with the direct response, then the RAPD is in the reactive pupil. An RAPD can occur due to downstream lesions in the pupillary light reflex pathway (such as in the optic tract or pretectal nuclei).[4] A transient RAPD can occur secondary to local anesthesia.[4] “Pupillary escape” is an abnormal pupillary response to a bright light, in which the pupil initially constricts to light and then slowly re-dilates to its original size.[4] Pupillary escape can occur on the side of a diseased optic nerve or retina, most often in patients with a central field defect.

Pupillary Dark Reflex

The dilation of the pupil in response to dark.[1] It can also occur due to a generalized sympathetic response to physical stimuli and can be enhanced by psychosensory stimuli; e.g., a sudden noise, pinching the back of the neck, or a passive return of the pupil to its relaxed state.

Pathway

In response to dark, the retina and optic tract fibers send signals to neurons in the hypothalamus, which then descend on the spinal cord lateral horn segments T1–T3.[2] The sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the lateral horn segments then send fibers to end on the sympathetic neurons in the superior cervical ganglion, which sends sympathetic postganglionic axons via the long ciliary nerve to the iris dilator muscle.

Ophthalmologic Considerations

Dilation lag may occur in patients with a defect in the sympathetic innervation of the pupil, such as in Horner syndrome.[4] It is described as greater anisocoria 5 seconds after light is removed from the eye, compared to 15 seconds after light is removed. Dilation lag can be tested by observing both pupils in dim light after a bright room light has been turned off. Normal pupils return to their widest size in 12–15 seconds; however, a pupil with a dilation lag may take up to 25 seconds to return to maximal size. Another method of testing for dilation lag is to take flash photographs at 5 seconds and 15 seconds to compare the difference in anisocoria; a >0.4-mm difference in anisocoria between the two indicates a positive test. Dilation lag detection using infrared videography is the most sensitive diagnostic test for Horner syndrome.[4]

Other Pupil Reflexes

Westphal–Piltz reflex was noted by Von Graefe, Westphal, and Piltz at different times. It is pupillary constriction in darkness or as part of closing eyelids when going to sleep. It is hypothesized that the Westphal–Piltz reflex is due to oculomotor disinhibition.[5]

Ciliospinal Reflex

A pupillary dilation in response to noxious stimuli (e.g., pinching) to the face, neck, or upper trunk.[6]

Pathway

The trigeminal nerve or cervical pain fibers, which are part of the lateral spinothalamic tract, carry the afferent inputs of the ciliospinal reflex.[6] Sympathetic fibers from the upper thoracic and lower cervical spinal cord make up the efferent portion of the ciliospinal reflex.[6] Central sympathetic fibers, which are the first-order neurons, begin in the hypothalamus and follow a path down the brainstem into the cervical spinal cord through the upper thoracic segments.[6] Second-order sympathetic neurons then exit the cervicothoracic cord from C8 to T2 through the dorsal spinal root and enter the paravertebral sympathetic chain and eventually the superior cervical ganglion.[6] Third-order neurons from the superior cervical ganglion travel up on the internal and external carotid arteries, with the pupil receiving sympathetic innervation from sympathetic fibers on the ophthalmic artery after branching off the internal carotid artery.[6] The ciliospinal reflex efferent branch bypasses the first-order neurons of the sympathetic nervous system and directly activates the second-order neurons; cutaneous stimulation of the neck activates sympathetic fibers through connections with the ciliospinal center at C8.[6][7]

Ophthalmologic Considerations

The ciliospinal reflex is absent in Horner syndrome due to loss of sympathetic input to the pupil.[6] [7] Patients in a barbiturate-induced coma may have a more easily elicited ciliospinal reflex, which may mimic a bilateral third cranial nerve palsy with dilated and unreactive pupils or midbrain compression with mid-positioned and unreactive pupils.[8] If the pupillary dilation is due to the ciliospinal reflex, prolonged pupillary light stimulation should constrict the pupils.[8] However, prolonged light stimulation cannot overcome pupillary dilation caused by bilateral third nerve palsies and midbrain dysfunction.[8]

Near Accommodative Triad

A 3-component reflex that assists in the redirection of gaze from a distant to a nearby object.[2] It consists of a pupillary accommodation reflex, a lens accommodation reflex, and a convergence reflex.

Afferent Pathway for Pupillary Constriction, Lens Accommodation, and Convergence

Afferent input from the retina is sent to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) via the optic tract.[2] Fibers from the LGN then project to the visual cortex.

Efferent Pathway for Pupillary Constriction

Efferent parasympathetic fibers from the E-W nucleus project to the ciliary ganglion via the oculomotor nerve, and then short ciliary nerves innervate the iris sphincter muscle, causing pupillary constriction.[2]

Efferent Pathway for Lens Accommodation

Efferent parasympathetic fibers from the E-W nucleus project to the ciliary ganglion via the oculomotor nerve, and then short ciliary nerves innervate the ciliary muscle, causing contraction.[2] Contraction of the ciliary muscle allows the lens zonular fibers to relax and the lens to become rounder, increasing its refractive power.

Efferent Pathway for Convergence

Efferent fibers from the medial rectus subnucleus of the oculomotor complex in the midbrain innervate the bilateral medial rectus muscles, causing convergence.[2]

Ophthalmologic Considerations

Accommodation deficits usually occur due to aging and presbyopia.[4] Isolated accommodation deficits can occur in healthy people or in patients with neurologic or systemic conditions (such as in children after a viral illness and in women before or after childbirth). Accommodation insufficiency is less commonly associated with primary ocular disorders (e.g., glaucoma in children and young adults causing secondary atrophy of the ciliary body, metastases in the suprachoroidal space damaging the ciliary neural plexus, ocular trauma), neuromuscular disorders (e.g., myasthenia gravis, botulism toxin, tetanus), focal or generalized neurologic diseases (e.g., supranuclear lesions, encephalitis, obstructive hydrocephalus, pineal tumors, Wilson disease), trauma, pharmacologic agents, and various other conditions. Light-near dissociation describes constriction of the pupils during the accommodative response that is stronger than the light response, and it is the primary feature of Argyll Robertson pupils in patients with neurosyphilis.[4] Light-near dissociation can also occur in patients with pregeniculate blindness, mesencephalic lesions, and damage to the parasympathetic innervation of the iris sphincter, as in Adie tonic pupil, described below.[4]

Adie tonic pupil is a relatively common, idiopathic condition caused by an acute postganglionic neuron denervation followed by appropriate and inappropriate reinnervation of the ciliary body and iris sphincter.[4] Immediately following denervation injury, there is a dilated pupil that is unresponsive to light or near stimulation. Ciliary muscle dysfunction gradually improves over several months as injured axons regenerate and reinnervate the ciliary muscle, and the pupil becomes smaller over time. While the near response of the pupil begins to improve, the light response remains impaired, causing light-near dissociation.

Corneal Reflex

Both eyes blink in response to tactile stimulation of the cornea.[2] It is the connection response from cranial nerve V (unilateral) to cranial nerve VII (bilateral).

Pathway

Inputs are first detected by trigeminal primary afferent fibers (i.e., free nerve endings in the cornea, which continue through the trigeminal nerve, Gasserian ganglion, root, and spinal trigeminal tract).[2] These primary afferent fibers synapse on secondary afferent fibers in the spinal trigeminal nucleus, which send axons to reticular formation interneurons that travel to the bilateral facial nuclei. Fibers from the facial nuclei motor neurons send axons through the facial nerve to the orbicularis oculi muscle, which lowers the eyelid.

Ophthalmologic Considerations

The corneal reflex can be utilized as a test of corneal sensation in patients who are obtunded or semicomatose.[4] However, an abnormal corneal reflex does not necessarily indicate a trigeminal nerve lesion, as unilateral ocular disease or weakness of the orbicularis oculi muscle can also be responsible for a decreased corneal response.[4] An abnormal blink reflex may be present in patients with various posterior fossa disorders, including acoustic neuroma, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, trigeminal nerve lesions, and brainstem strokes, tumors, or syrinxes.[4] There are various other stimuli that can induce a “trigeminal blink reflex” by stimulating the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, including a gentle tap on the forehead, cutaneous stimulation, or supraorbital nerve stimulation.[4]

Vestibulo-ocular Reflex

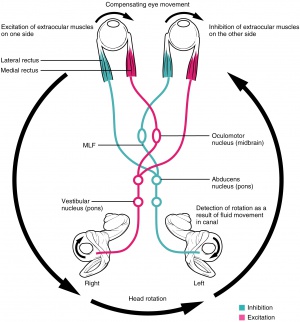

The vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) allows for eye movements in the opposite direction of head movement to maintain steady gaze and prevent retinal image slip.[4]

Pathway

Motion signals from the utricle, saccule, and/or semicircular canals in the inner ear travel through the uticular, saccular, and/or ampullary nerves to areas in the vestibular nucleus, sending output to cranial nerve III, IV, and VI nuclei to innervate the corresponding muscles.[4] Horizontal VOR involves coordination of the abducens and oculomotor nuclei via the medial longitudinal fasciculus.

Ophthalmologic Considerations

An abnormal VOR will involve catch-up saccades while the patient rotates his or her head, and it can indicate bilateral, complete, or severe (>90%) loss of vestibular function.[9] VOR can be assessed in several ways. During the Doll’s eye maneuver (oculocephalic reflex), the patient continuously fixates on an object while the examiner moves his or her head from side to side and watches the patient’s eyes for catch-up saccades. VOR can also be assessed via dynamic visual acuity, when multiple visual acuity measurements are taken as the examiner oscillates the patient’s head. A loss of ≥3 lines of visual acuity is abnormal and indicative that the patient’s VOR is grossly reduced. VOR can be evaluated with an ophthalmoscope to view the optic disc while the patient rotates his or her head; if the VOR is abnormal, catch-up saccades will manifest as jerkiness of the optic disc. Caloric stimulation can also be used to examine the VOR.[4] Irrigation of the external auditory meatus with ice water causes convection currents of the vestibular endolymph that displace the cupula in the semicircular canal, which induces tonic deviation of the eyes toward the stimulated ear.[4] Examination of the VOR via head rotation or caloric stimulation can be useful in the evaluation of unconscious patients, as tonic eye deviation indicates preserved pontine function.[4]

Bell Phenomenon (palpebral oculogyric reflex)

An upward and lateral deviation of the eyes during eyelid closure against resistance. It is particularly prominent in patients with lower motor neuron facial paralysis and lagophthalmos (i.e., incomplete eyelid closure).[10]

Pathway

Afferent fibers are carried by facial nerves. Efferent fibers travel in the oculomotor nerve to the superior rectus muscle, causing an upward deviation of the eyes.

Ophthalmologic Considerations

Bell phenomenon is present in about 90% of the population.[11] It is especially visible in patients with Bell palsy, an acute disorder of the facial nerve, due to failure of adequate eyelid closure.[10] The presence or absence of this reflex can be useful in the diagnosis of many systemic and local diseases.[11] In supranuclear palsy, which can occur with Steele-Richardson syndrome, Parinaud syndrome, and double elevator palsy, patients cannot elevate their eyes but can do so on attempting the Bell phenomenon. Diseases that affect tethering of the inferior rectus muscle, such as thyroid eye disease, or cause muscular weakness, such as myasthenia gravis, can cause the reflex to be absent; this may also occur with local ocular diseases such as blowout fractures of the orbital floor, infiltrative orbital pseudotumors, and restrictive syndromes. An absent reflex may be the only neurologic abnormality in patients with idiopathic epilepsy, Sturge-Weber syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis.

Lacrimatory Reflex

Tear secretion in response to various stimuli, such as physical and chemical stimuli to the cornea, conjunctiva and nasal mucosa, bright lights, emotional upset, vomiting, coughing, and yawning.[1]

Pathway

Afferent signals are sent from the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.[1] The superior salivatory nucleus in the pons gives off parasympathetic fibers that join other parasympathetic efferents from the salivatory nucleus.[1] These fibers run with gustatory afferents parallel to the facial nerve as the nervus intermedius and exit at the geniculate ganglion.[12][13] The parasympathetic fibers then leave cranial nerve VII as the greater superficial petrosal nerve and synapse in the sphenopalatine ganglion. Postganglionic fibers travel with the lacrimal nerve to reach the lacrimal gland and cause reflex tearing.

Ophthalmologic Considerations

Abnormalities in this pathway may cause hypolacrimation, hyperlacrimation, or inappropriate lacrimation.[4] Hypolacrimation may be secondary to deafferentation of the tear reflex on one side, which can be due to severe trigeminal neuropathy or damage to the parasympathetic lacrimal fibers in the efferent limb of the reflex.[4] Lesions may affect the nervus intermedius, greater superficial petrosal nerve, sphenopalatine ganglion, or zygomaticotemporal nerve. Hyperlacrimation may be due to excessive triggers of the tear reflex arc or efferent parasympathetic fiber overstimulation. Inappropriate lacrimation can occur with the gustolacrimal reflex, described below.

The gustolacrimal reflex is also called “crocodile tears” or Bogorad syndrome.[4] The reflex describes unilateral lacrimation when a person eats or drinks.[14] It usually occurs in conjunction with Bell palsy or traumatic facial paralysis, due to misdirection of regenerating gustatory fibers from either the facial or glossopharyngeal nerves that are responsible for taste. The nerves may redirect themselves through the greater superficial petrosal nerve to reach the lacrimal gland, causing ipsilateral tearing when the patient eats.

Optokinetic Reflex

Also called optokinetic nystagmus, it consists of 2 components that serve to stabilize images on the retina: a slow pursuit phase and a fast “reflex” or “refixation” phase.[15] The reflex is classically tested with an optokinetic drum or tape with alternating stripes of varying spatial frequencies.

Pathway for Slow Pursuit Phase

Afferent signals from the retina are conveyed through the visual pathways to the occipital lobe, which sends impulses to the pontine horizontal gaze center.[15] The horizontal gaze center coordinates signals to the abducens and oculomotor nuclei to reflexively induce slow movement of the eyes.

Pathway for Fast Refixation Phase

Afferent signals from the retina are conveyed to the frontal eye field, which sends signals to the superior colliculus, activating the pontine horizontal gaze center.[15][16] The horizontal gaze center coordinates signals to the abducens and oculomotor nuclei to allow for a rapid saccade in the opposite direction of the pursuit movement to refixate the gaze.

Ophthalmologic Considerations

The optokinetic reflex can be used to assess visual acuity in infants and children.[15] It will be present in newborns, semi-obtunded patients, and patients who are attempting to malinger. Lesions of the deep parietal tract, a region close to where efferent pursuit fibers pass close to afferent optic radiations, will show directional asymmetry of the optokinetic reflex response. This response can also be used to evaluate for suspected subclinical internuclear ophthalmoplegia, which will show a slower response by the medial rectus on the side of the lesion, and for suspected Parinaud syndrome, in which the use of a downward reflex target will accentuate convergent retraction movements on attempted upgaze. The optokinetic reflex response is not fail-proof, however, as attentional factors can affect the outcome.

Oculocardiac Reflex

The oculocardiac reflex is a dysrhythmic physiologic response to physical stimulation of the eye or adnexa. It is defined by a 10%–20% decrease in the resting heart rate and/or the occurrence of any arrhythmia induced by traction or entrapment of the extraocular muscles and/or pressure on the eyeball sustained for at least 5 seconds.[17]

Pathway

Short ciliary nerves come together at the ciliary ganglion and converge with the long ciliary nerve to form the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, which continues to the Gasserian ganglion and then the main sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve.[17][18] Fibers synapse with the visceral motor nuclei of the vagus nerve in the reticular formation. Vagal outflow via the cardiac depressor nerve stimulates muscarinic cholinergic receptors, which results in sinus bradycardia that can progress to atrial/ventral block, ventricular tachycardia, or asystole.[17]

Ophthalmologic Considerations

This reflex is most commonly seen in children, particularly during strabismus surgery.[17] Incidence varies between 50% and 90%,[19] and children aged 2–5 years are thought to be more affected due to high resting vagal tone.[17] Although intravenous atropine given within 30 minutes of surgery is believed to reduce the incidence of the oculocardiac reflex, it is no longer recommended for routine prophylaxis.[18] Retrobulbar anesthesia may block the afferent limb of the oculocardiac reflex in adults; however, it is rarely used in children.[18] The reflex can also occur in patients with entrapment after orbital floor fracture.

Oculorespiratory Reflex

Shallow breathing, slowed respiratory rate, or respiratory arrest due to pressure on the eye or orbit or stretching of the extraocular muscles.

Pathway

Short ciliary nerves come together at the ciliary ganglion and converge with the long ciliary nerve to form the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, which continues to the Gasserian ganglion and then the main sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve.[20] Signals from the pneumotaxic respiratory center in the ventrolateral tegmentum of the pons reach the medullary respiratory area and travel through the phrenic and other respiratory nerves, which lead to bradypnea, irregular respiratory movements, and respiratory arrest.[20]

Ophthalmologic Considerations

This reflex is sometimes observed during strabismus surgery.[20] It is often concealed by controlled ventilation; however, spontaneously breathing patients should be monitored carefully, as the reflex may lead to hypercarbia and hypoxemia. Atropine does not have an effect on the reflex.

Oculo-Emetic Reflex

Increased nausea and vomiting secondary to extensive manipulation of extraocular muscles.[21]

Pathway

The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve carries impulses to the main sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. The vomiting center in the medulla causes increased vagal output that leads to nausea and vomiting.[19][21]

Ophthalmologic Considerations

This reflex may explain why patients undergoing ophthalmic surgery that involves extensive manipulation of extraocular muscles are prone to develop postoperative nausea and vomiting.[21] Retrobulbar or peribulbar blocks decrease afferent signaling and therefore can reduce the incidence of the oculo-emetic reflex.[22]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Hunyor AP. Reflexes and the eye. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1994;22(3):155-159.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Dragoi V. Ocular motor system. In: Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences. McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/index.htm. Accessed July 1, 2025.

- ↑ Sensory systems. In: Felten DL, O’Banion MK, Maida MS, eds. Netter’s Atlas of Neuroscience. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2016: 353-389.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, et al, eds. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- ↑ Bender MB. Eyelid closure reaction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1943;29(3):435-440.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Mullaguri N, Katyal N, Sarwal A, et al. Pitfall in pupillometry: exaggerated ciliospinal reflex in a patient in barbiturate coma mimicking a nonreactive pupil. Cureus. 2017;9(12):e2004.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Havelius U, Heuck M, Milos P, et al. Ciliospinal reflex response in cluster headache. Headache. 1996;36(9):568-573.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Andrefsky JC, Frank JI, Chyatte D. The ciliospinal reflex in pentobarbital coma. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(4):644-646.

- ↑ Bronstein AM. Vestibular reflexes and positional movements. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(3):289-293.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Patel DK, Levin KH. Bell palsy: Clinical examination and management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2015;82(7):419-426.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Francis IC, Loughhead JA. Bell's phenomenon: a study of 508 Aust J Ophthalmol'. 1984;12(1):15-21.

- ↑ Secretory apparatus. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 7. Oculofacial Plastic and Orbital Surgery. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2017-2018: 251-252.

- ↑ Parasympathetic pathways. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 5. Neuro-Ophthalmology. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2017-2018: 54-56.

- ↑ Montoya FJ, Riddell CE, Caesar R, et al. Treatment of gustatory hyperlacrimation (crocodile tears) with injection of botulinum toxin into the lacrimal gland. Eye (Lond). 2002;16(6):705-709.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 London R. Optokinetic nystagmus: a review of pathways, techniques and selected diagnostic applications. J Am Optom Assoc. 1982;53(10):791-798.

- ↑ Blackwood W, Dix MR, Rudge P. The cerebral pathways of optokinetic nystagmus: a neuro-anatomical study. Brain. 1975;98(2):297-308.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Bharati SJ, Chowdhury T. The oculocardiac reflex. In: Chowdhury T, Schaller BJ, eds. Trigeminocardiac Reflex. Academic Press; 2015: 89-99.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Cook-Sather SD. Ophthalmic problems and complications. In: Atlee JL, ed. Complications in Anesthesia. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2007: 692-697.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gupta M, Rhee DJ. Ophthalmic anesthesia. Glaucoma. 2015;2(2):734-748.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Blanc VF, Jacob JL, Milot J, et al. The oculorespiratory reflex revisited. Can J Anaesthesia. 1988;35(5):468-472.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Sharma D, Sharma N, Kumar Mishra A, et al. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: a review. Int J Cur Res Rev. 2014;6(20):48-54.

- ↑ James I. Anaesthesia for paediatric eye surgery. CEACCP. 2008;8(1):5-10.