User talk:Nuno.RodriguesAlves

Immune Recovery Uveitis (IRU)

Immune recovery uveitis (IRU) is a form of intraocular inflammation associated with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), typically occurring in HIV-infected patients with a history of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis following the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). It reflects a dysregulated immune response to residual CMV antigens in the setting of rapid immune restoration and remains a leading cause of vision loss in this population due to complications such as cystoid macular edema, epiretinal membranes, and optic disc edema.[1] IRU is increasingly recognized beyond HIV, with IRU-like manifestations described in non-HIV individuals recovering from immunosuppression due to malignancy, transplantation, or autoimmune disease. These cases suggest a broader spectrum of immune recovery-associated uveitis, not limited to CMV or HIV.[1] This evolving understanding highlights the need for expanded diagnostic criteria and targeted management strategies.

Contents

- Epidemiology

- Pathophysiology

- Biomarkers

- Clinical Presentation

- § Complications

- § Risk Factors

- Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

- Management

- § Medical Treatment

- § Surgical Management

- Conclusion

- References

Epidemiology

The incidence of IRU varies and is influenced by factors such as the HAART era and immune status at the time of initiation. [2, 3] Early reports estimated that IRU occurred in 10-17% of CMV retinitis (CMVR) cases during the initial HAART era, with over half of the cases developing inflammation after only a modest increase in CD4+ T-cell count (100–150 cells/mm³).[3] The timing of HAART initiation in CMVR is critical. Starting HAART before completing CMV induction therapy increases the risk of IRU. [4, 5] Conversely, controlling CMVR prior to immune reconstitution significantly reduces both the occurrence and severity of IRU. [6] Ongoing anti-CMV therapy is advised to suppress viral antigen load until adequate immune recovery is achieved. [7]

Pathophysiology

CMV is the most common opportunistic ocular pathogen in advanced HIV infection, typically occurring when CD4+ T-cell counts fall below 50 cells/μL. CMV retinitis results from hematogenous spread and reactivation of latent CMV, leading to retinal necrosis. [5, 8] Classic fundoscopic findings include confluent areas of retinal whitening with hemorrhages (“pizza pie retinopathy”), granular satellite lesions, and retinal vasculitis with perivascular sheathing. CMVR often leads to retinal atrophy and irreversible vision loss. [9] HAART has reduced the incidence of CMVR but has introduced immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), a paradoxical inflammatory response to residual or subclinical infections. IRIS typically develops within 3 months of HAART initiation but can occur up to 12 months later. [3, 10] Diagnostic criteria for IRIS include:

- Confirmed HIV infection

- Temporal association with HAART

- Immunologic response (↓ HIV RNA, ↑ CD4+ count)

- Clinical deterioration due to inflammation

- Exclusion of other causes

IRU is the most common ocular manifestation of IRIS and is considered an immune-mediated inflammatory response to residual intraocular CMV antigen. It can develop weeks to months after HAART initiation, even in the absence of active retinitis. The inflammation is believed to be driven by persistent antigenic stimulation within the eye, despite systemic viral suppression and anti-CMV therapy. [1]

Biomarkers

Biologic markers may help distinguish IRU from active CMVR:

- Cytokine profile: Elevated IL-12, reduced IL-6, and absence of detectable CMV DNA in aqueous or vitreous samples suggest IRU rather than active infection. [8, 11]

- Inflammatory mediators: Increased levels of IP-10, PDGF-AA, G-CSF, MCP-1, fractalkine, and Flt-3L have been identified in the aqueous humor of IRU patients, indicating a distinct immunologic signature. [12, 13]

- HLA associations: IRU has been linked to specific HLA haplotypes, including HLA-A2, HLA-B44, HLA-DR4, and HLA-B8-18, which may predispose individuals to heightened inflammatory responses during immune recovery. [14]

Clinical Presentation

IRU is a clinical entity with variable manifestations, ranging from anterior uveitis to severe vitritis, with potential complications that can significantly impact visual function. The severity of inflammation is influenced by several factors, including the degree of immune reconstitution, the extent of CMVR, the amount of intraocular CMV antigen, and previous treatment. [1, 4]

- Symptoms: Floaters and moderate vision loss (typically between 20/40 to 20/200).

- Inflammation: Anterior chamber inflammation and vitreous haze often develop after HAART initiation.

- CMVR Activity: Active CMVR is not typically present in IRU, as improved immune function controls the infection.

Complications

- Cystoid macular edema (CME): The most common cause of vision loss in IRU, with a 20-fold increased risk.

- Anterior segment inflammation

- Synechiae

- Cataracts

- Vitreomacular traction

- Epiretinal membrane (ERM) formation

- Macular hole

- Proliferative vitreoretinopathy and retinal detachment

- Frosted branch angiitis

- Papillitis

- Neovascularization of the retina or optic disc

- Uveitic glaucoma

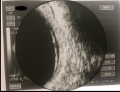

Fig. 1 Clinical presentation of IRU. Fig. 1A represents a fundoscopy with discrete vitritis, macular edema, optic disc pallor and peripheral atrophic chorioretinal scars with no signs of activity of CMVR in a patient with microscopic polyangiitis treated with mycophenolate mofetil referred for observation due to complaints of left reduced visual acuity and floaters that started ten months after suspension of immunosuppressive therapy due to CMV colitis. Fig. 1B shows the optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the same patient with cystoid macular edema.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors have been identified for the development of IRU: [2]

- Increased CD4+ T-cell count: A rapid rise in CD4+ count (100–199 cells/μL) is strongly associated with higher IRU risk (OR 21.8).

- Intravitreal cidofovir (OR 19.1).

- CMVR extension ≥25% (OR 2.52).

Conversely, the following factors are associated with a reduced risk of IRU:

- Posterior pole lesion (OR 0.43).

- Male gender (OR 0.23).

- HIV viral load >400 copies/mL (OR 0.26).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

IRU is an exclusionary diagnosis commonly observed in HIV patients on HAART who experience a significant rise in CD4+ T-cell count (>100 cells/mm³) and develop paradoxical intraocular inflammation in eyes with a history of CMVR or other ocular infections. The diagnosis requires ruling out other causes of inflammation, including drug toxicities (e.g., cidofovir, rifabutin), new infections (e.g., ocular tuberculosis, syphilitic uveitis, toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis), and conditions like sarcoidosis. [1, 4, 9] In non-HIV patients, IRU-like inflammation may occur following immune recovery after reduced immunosuppressive treatment, seen in conditions such as lymphoma, Wegener granulomatosis, Good Syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, leukemia, and after organ transplants (renal or bone marrow). [15–26] These cases may present ocular inflammation resembling IRU due to the restoration of immune function. Diagnosis involves clinical evaluation and diagnostic tests, such as multimodal imaging, ocular PCR, and vitrectomy, to exclude other causes. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential for accurate diagnosis and management.[1]

Management

The management of IRU involves considering various factors, including the extent and activity of the underlying CMV retinitis, the presence or absence of non-ocular IRIS, the site of intraocular inflammation, the existence of any associated ocular complications, particularly macular edema, and the patient’s general health [1, 4].

Medical Treatment

- Topical corticosteroids: Used for anterior chamber inflammation.

- Observation: Mild vitritis without macular edema may be monitored without treatment.

- Oral corticosteroids or periocular injections: For severe vitritis or CME, though effectiveness is limited.

- Intravitreal corticosteroids: For refractory cases, but careful monitoring is needed to prevent complications like increased intraocular pressure and cataract formation, and CMVR reactivation, which can be prevented by restarting anti-CMV therapy

- Fluocinolone acetonide implants: May improve CME associated with IRU.

- Anti-VEGF agents: Aflibercept has shown effectiveness in treating IRU-induced CME, potentially due to its higher affinity for VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PlGF.

Discontinuing antiretroviral therapy is not recommended because it reduces the CD4+ T lymphocyte count and increases the risk of opportunistic infections. Patients with CMVR who are receiving antiretroviral regimens should continue with anti-CMV maintenance therapy (Oral Valganciclovir 900 mg daily) until the IRU is resolved and sustained immune recovery is achieved (CD4+ T lymphocytes ≥ 100 cells/µL for 3-6 months). Even after discontinuation of anti-CMV therapy, patients with a history of CMVR should be closely monitored at 3-month intervals, as they remain at risk for recurrence. [27] International guidelines recommend initiation of HAART within two weeks of commencing anti-CMV therapy in HIV/CMVR patients, although these recommendations are based on expert opinions and not empirical evidence. [60], [61].

Surgical Treatment:

Indications for surgery: Vitreomacular traction, ERM, cataract, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy may require surgical intervention to improve visual outcomes. [4]

Conclusion

IRU is an intraocular inflammation and may be the sole manifestation of IRIS, involving a complex interplay between immune reconstitution and inflammatory responses. Notably, IRU can occur even in individuals with modest immune recovery and may involve underlying mechanisms beyond CMV infection alone. Therefore, diligent monitoring and early detection of IRU are essential, given the potential for diverse etiologies of immunosuppression. Accurate diagnosis of IRU relies on comprehensive assessments that incorporate clinical and laboratory findings, potentially utilizing advanced diagnostic modalities when necessary. The broad spectrum of conditions associated with IRU-like responses challenges our current understanding and emphasizes the need for a comprehensive definition and diagnostic criteria for non-HIV-type IRIS. Such an approach would facilitate clinical decision-making and enable tailored management strategies for patients. Further research is warranted to optimize treatment approaches, explore novel therapeutic targets, and improve patient outcomes for both HIV and non-HIV individuals affected by IRU.

References

- Rodrigues Alves N, Barão C, Mota C, et al (2024) Immune recovery uveitis: a focus review. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 262:2703–2712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-024-06415-y

- Kempen JH, Min YI, Freeman WR, et al (2006) Risk of Immune Recovery Uveitis in Patients with AIDS and Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Ophthalmology 113:684–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.067

- Sudharshan S, Kaleemunnisha S, Banu AA, et al (2013) Ocular lesions in 1,000 consecutive HIV-positive patients in India: a long-term study. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 3:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1869-5760-3-2

- Urban B, Bakunowicz-Łazarczyk A, Michalczuk M (2014) Immune Recovery Uveitis: Pathogenesis, Clinical Symptoms, and Treatment. Mediators Inflamm 2014:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/971417

- Munro M, Yadavalli T, Fonteh C, et al (2019) Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in HIV and Non-HIV Individuals. Microorganisms 8:55. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8010055

- Ortega-Larrocea G, Espinosa E, Reyes-Terán G (2005) Lower incidence and severity of cytomegalovirus-associated immune recovery uveitis in HIV-infected patients with delayed highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 19:735–738. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000166100.36638.97

- Kuppermann BD, Holland GN (2000) Immune recovery uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 130:103–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00537-7

- SCHRIER RD, SONG M-K, SMITH IL, et al (2006) INTRAOCULAR VIRAL AND IMMUNE PATHOGENESIS OF IMMUNE RECOVERY UVEITIS IN PATIENTS WITH HEALED CYTOMEGALOVIRUS RETINITIS. Retina 26:165–169. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006982-200602000-00007

- Port AD, Orlin A, Kiss S, et al (2017) Cytomegalovirus Retinitis: A Review. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 33:224–234. https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2016.0140

- Ratnam I, Chiu C, Kandala N-B, Easterbrook PJ (2006) Incidence and Risk Factors for Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome in an Ethnically Diverse HIV Type 1-Infected Cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases 42:418–427. https://doi.org/10.1086/499356

- Rios LS, Vallochi AL, Muccioli C, et al (2005) Cytokine profile in response to Cytomegalovirus associated with immune recovery syndrome after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 40:711–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80087-0

- Modorati G, Miserocchi E, Brancato R (2005) Immune Recovery Uveitis and Human Leukocyte Antigen Typing: A Report on Four Patients. Eur J Ophthalmol 15:607–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/112067210501500511

- Vrabec TR (2004) Posterior segment manifestations of HIV/AIDS. Surv Ophthalmol 49:131–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.12.008

- Duraikkannu D, Akbar AB, Sudharshan S, et al (2023) Differential Expression of miRNA-192 is a Potential Biomarker for HIV Associated Immune Recovery Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 31:566–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2022.2106247

- Lavine JA, Singh AD, Baynes K, Srivastava SK (2021) IMMUNE RECOVERY UVEITIS-LIKE SYNDROME MIMICKING RECURRENT T-CELL LYMPHOMA AFTER AUTOLOGOUS BONE MARROW TRANSPLANT. Retin Cases Brief Rep 15:407–411. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICB.0000000000000829

- Yavuz Saricay L, Baldwin G, Leake K, et al (2023) Cytomegalovirus retinitis and immune recovery uveitis in a pediatric patient with leukemia. Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 27:52–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2022.10.004

- Sánchez-Vicente JL, Rueda-Rueda T, Moruno-Rodríguez A, et al (2019) Respuesta similar a la uveítis de recuperación inmune en un paciente con retinitis herpética como complicación de una leucemia de células peludas. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 94:545–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oftal.2019.07.012

- Baker ML, Allen P, Shortt J, et al (2007) Immune recovery uveitis in an HIV-negative individual†. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 35:189–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01439.x

- Bessho K, Schrier RD, Freeman WR (2007) IMMUNE RECOVERY UVEITIS IN A CMV RETINITIS PATIENT WITHOUT HIV INFECTION. Retin Cases Brief Rep 1:52–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ICB.0000256952.24403.42

- Miserocchi E, Modorati G, Brancato R (2005) Immune Recovery Uveitis in a iatrogenically Immunosuppressed Patient. Eur J Ophthalmol 15:510–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/112067210501500417

- Tai C-C, Chao Y-J, Hwang D-K (2022) Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor-induced Immune Recovery Uveitis Associated with Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in the Setting of Good Syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 30:1519–1521. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2021.1881565

- Yanagisawa K, Ogawa Y, Hosogai M, et al (2017) Cytomegalovirus retinitis followed by immune recovery uveitis in an elderly patient with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing administration of methotrexate and tofacitinib combination therapy. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 23:572–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2017.03.002

- Downes KM, Tarasewicz D, Weisberg LJ, Cunningham ET (2016) Good syndrome and other causes of cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV-negative patients—case report and comprehensive review of the literature. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 6:1–19

- Wimmersberger Y, Balaskas K, Gander M, et al (2011) Immune recovery uveitis occurring after chemotherapy and ocular CMV infection in chronic lymphatic leukaemia. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 228:358–359

- Agarwal A, Kumari N, Trehan A, et al (2014) Outcome of cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompromised patients without Human Immunodeficiency Virus treated with intravitreal ganciclovir injection. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 252:1393–1401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-014-2587-5

- Kuo IC, Kempen JH, Dunn JP, et al (2004) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of cytomegalovirus retinitis in persons without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol 138:338–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.015

- Sen HN, Albini TA, Burkholder BM, et al (2022) 2022-2023 Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 9: Uveitis and Ocular Inflammation. San Francisco

- (2023) Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-andadolescent- opportunistic-infection. Accessed (8th of May 2023)

- (2015) GUIDELINE ON WHEN TO START ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY AND ON PRE-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS FOR HIV GUIDELINES