Toxoplasmosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of infectious retinochroiditis in humans.

Etiology

The causative organism, Toxoplasma gondii, is a single-cell, obligate, intracellular protozoan parasite. Cats are the definitive host for T. gondii; however, humans and a wide range of mammals, birds, and reptiles may also serve as intermediate hosts. T. gondii has 3 forms: (1) the oocyst (soil form); (2) the tachyzoite (active infectious form); and (3) the tissue cyst (latent form).

Epidemiology

T. gondii’s presence in nature is widespread, but human infections are not equally distributed around the world. It has been estimated that 1 billion people are infected worldwide, with rates of infection highest in tropical areas and lower in dry, arid areas and cold areas. This likely reflects the environments which are most amenable to the organism's proliferation. The rates of ocular disease secondary to toxoplasmosis are estimated to be around 2% in the United States, 18% in Brazil, and up to 43% in Africa.

Risk Factors

The main risk factor of toxoplasmosis infection is exposure to environments where the infectious organism is found, especially those frequented by felines. Other risk factors include male sex, owning more than 3 cats or kittens, and eating raw or undercooked meat (e.g., lamb, ground beef, shellfish, game).

General Pathology

Necrotizing retinitis occurs with toxoplasmosis, along with vasculitis and destruction of the retina. Below are listed the classic and atypical findings which have been reported on physical examination.

Classic Findings

- White focal retinitis with overlying vitreous inflammation (“headlight in the fog”)

- Accompanying nearby or adjacent pigmented retinochoroidal scars

- Vitreous inflammation (mild, moderate, or severe)

- Secondary nongranulomatous iridocyclitis

- Granulomatous and stellate keratic precipitates (possible)

- Inflammatory ocular hypertension (10%–15% of cases)

- Retinal vasculitis (typically near the focus of retinochoroiditis)

Atypical Findings Which Can Accompany Retinochoroiditis

- Papillitis

- Neuroretinitis

- Retrobulbar neuritis

- Scleritis

- Retinal detachment

- Punctate outer retinitis

- Branch retinal artery occlusion

- Frosted branch angiitis

- Coats’-type response

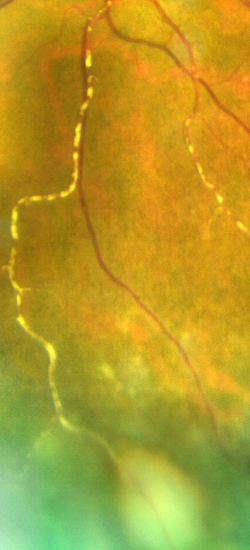

- Kyrieleis arteritis or segmental retinal arteritis[2]

- Fuchs’-like anterior uveitis

- Multifocal diffuse necrotizing retinitis

Atypical Findings Which Can Exist in the Absence of Retinochoroiditis

- Retinal vasculitis

- Unilateral neuroretinitis (optic disk edema, macular star)

- Inflammation in absence of overt necrotizing retinitis

- Unilateral pigmentary retinopathy mimicking retinitis pigmentosa

Recurrence

Recurrent lesions tend to occur at the margins of old scars, but they also can occur elsewhere in the fundus. The risk of recurrence is highest within the first year of the initial episode. Older age also conveys a higher risk of recurrence. The American Academy of Ophthalmology published a report entitled "Interventions for Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis" and agreed that there was level 2 evidence that long-term prophylactic treatment with combined trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole might reduce recurrences.

Symptoms

Typical symptoms of active disease are floaters and blurred vision. If the patient has a secondary iritis, eye pain and redness may also be seen.

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnostic Evaluations

Because of the high prevalence of positive toxoplasma titers in many populations, the use of serology in diagnosing toxoplasmosis is mainly limited to reassuring the clinician that toxoplasmosis should remain in the differential. If the immunoglobulin G titers are completely negative, down to a 1:1 dilution, then toxoplasmosis is completely ruled out in an immunocompetent person. It is possible that an immunosuppressed patient could have completely negative immunoglobulin titers and have still active ocular toxoplasmosis infection.

The development of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been very helpful for the diagnosis of atypical or difficult cases. Detection of T. gondii DNA by PCR in both aqueous humor and vitreous fluid is both sensitive and specific.

Differential Diagnosis

Infectious

- Tuberculosis

- Viral retinitis (cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus)

- Toxocariasis

- Bartonella

- Syphilis

- Endophthalmitis

Autoimmune

- Behçet disease

- Systemic autoimmune diseases

- Retinal vasculitis

Management

Not all lesions warrant treatment. Indications for treatment include:

- Macular threatening or optic nerve or papillomacular lesions

- Close proximity of lesions to major retinal vessels

- Dense vitritis

- Marked visual impairment

- Larger lesions

- Pregnancy

- Monocular status

- Immunocompromised host

Medical Therapy

Systemic Pyrimethamine, Sulfadiazine, and Corticosteroids

This is the classic triple therapy used in the treatment of toxoplasmosis. In a survey conducted among American Uveitis Society members, this combination triple therapy was cited as the treatment of choice by 32% of respondents. Of note, pyrimethamine is a folic acid antagonist and can cause dose-related suppression of the bone marrow, which is mitigated by concurrent administration of folinic acid (leucovorin).

Systemic Clindamycin

An additional 27% of American Uveitis Society survey respondents said they added clindamycin to the previously mentioned triple therapy. In general, treatment is given until the inflammatory reaction begins to decrease and the retinal lesion shows signs of healing, which is usually 4 to 6 weeks.

Systemic Azithromycin

Rothova et al reported successful treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent patients with azithromycin alone.

Other Treatments

Other toxoplasmosis treatments include systemic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and intravitreal clindamycin (alone or in combination with steroids).

Surgery

Surgical treatment is not indicated for the treatment of toxoplasmosis infection, though it may be required if the patient has a retinal detachment occurring as a complication of toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis.

Prognosis

In general, final visual acuity depends on the location of the active infection, degree of inflammation, and development of complications related to ocular inflammation. Due to possible disease recurrence, long-term follow-up is recommended.

Patient Education

Clinicians should let parents and older children with congenital infection know that late-onset retinal lesions and relapse can occur many years after birth, though they should also be reassured that risk of bilateral visual impairment appears to be low. Identifying activation or reactivation early and getting treated will give the best prognosis.

Additional Resources

- Porter D. What is toxoplasmosis? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye Health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-toxoplasmosis. Published September 30, 2024. Accessed June 12, 2025.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Toxoplasmosis. https://www.aao.org/image/toxoplasmosis-4 Accessed August 24, 2022.

- ↑ Khadamy J. Atypical ocular toxoplasmosis: multifocal segmental retinal arteritis (Kyrieleis arteritis) and peripheral choroidal lesion. Cureus. 2023;15(10): e47060.

- Jones JL, Dargelas V, Roberts J, et al. Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 ;49(6):878-884.

- Bosch-Driessen LH, Plaisier MB, Stilma JS, et al. Reactivations of ocular toxoplasmosis after cataract extraction. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(1):41-45.

- Kim SJ, Scott IU, Brown GC, et al. Interventions for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(2):371-378.

- Conrady CD, Besirli CG, Baumal CR, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis after exposure to wild game. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022;30(3):527-532.

- Rothova A, Meenken C, Buitenhuis HJ, et al. Therapy for ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol.1993;115:517-523.