Scleritis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

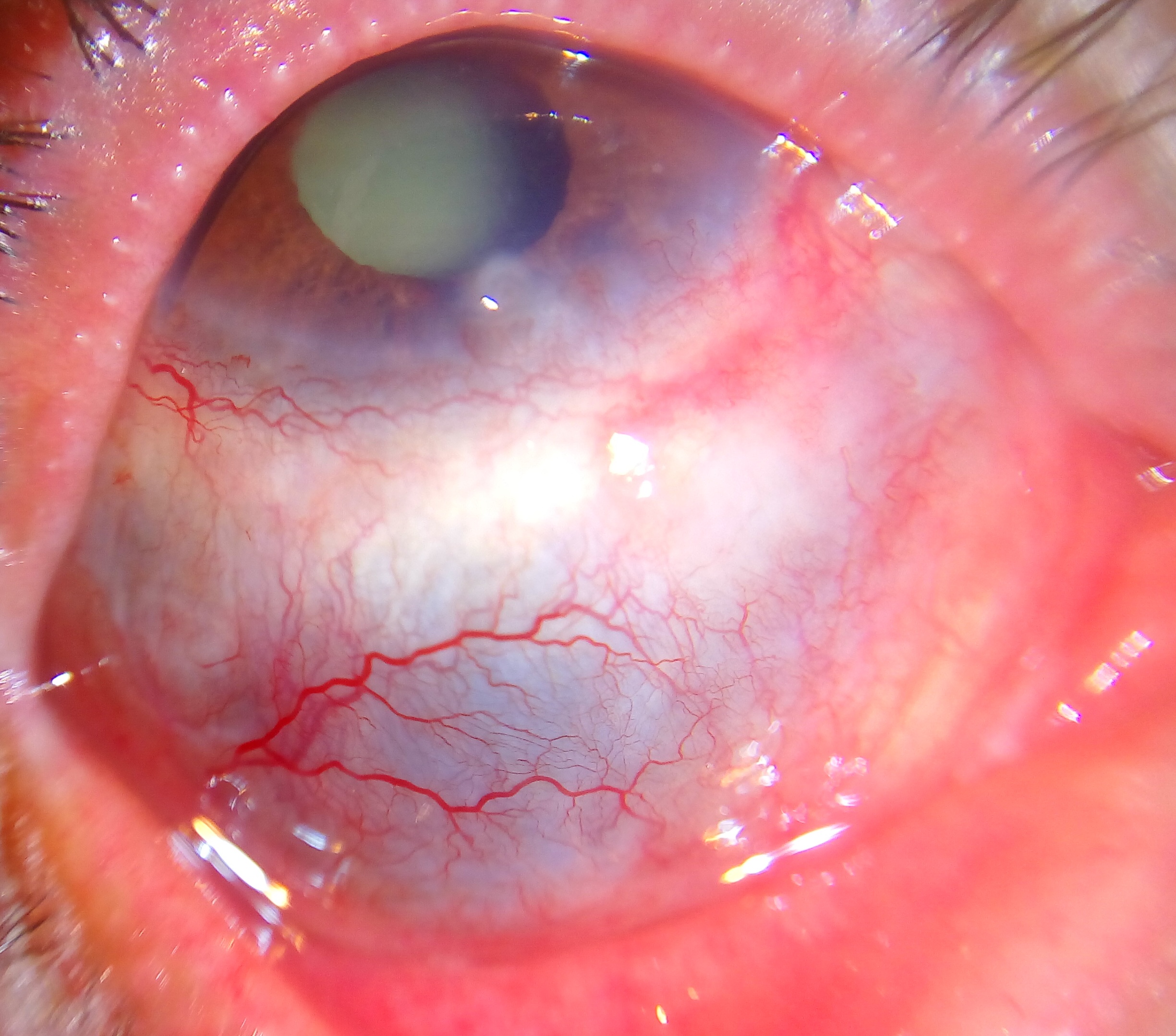

Scleritis is the inflammation in the episcleral and scleral tissues with injection in both superficial and deep episcleral vessels. It may involve the cornea, adjacent episclera, and the uvea and thus can be vision threatening. Scleritis is often associated with an underlying systemic disease in up to 50% of patients.

Disease Entity

- Scleritis and episcleritis ICD9 379.0 (excludes syphilitic episcleritis 095.0),

- Scleritis, Unspecified ICD9 379.00,

- Anterior scleritis ICD9 379.03,

- Posterior scleritis ICD9 379.07

Disease

Scleritis, or inflammation of the sclera, can present as a painful red eye with or without vision loss. The most common form, anterior scleritis, is defined as scleral inflammation anterior to the extraocular recti muscles. Posterior scleritis is defined as involvement of the sclera posterior to the insertion of the rectus muscles.

Anterior scleritis, the most common form, can be subdivided into diffuse, nodular, or necrotizing forms. In the diffuse form, anterior scleral edema is present along with dilation of the deep episcleral vessels. The entire anterior sclera or just a portion may be involved. In nodular disease, a distinct nodule of scleral edema is present. The nodules may be single or multiple in appearance and are often tender to palpation. Necrotizing anterior scleritis is the most severe form of scleritis. It is characterized by severe pain and extreme scleral tenderness. Severe vasculitis, as well as infarction and necrosis with exposure of the choroid, may result. A rare form of necrotizing anterior scleritis without pain can be called scleromalacia perforans. The sclera is notably white, avascular, and thin. Both choroidal exposure and staphyloma formation may occur.

Posterior scleritis, although rare, can manifest as serous retinal detachment, choroidal folds, or both. There is often pain upon eye movement and loss of vision.

Etiology

There are many connective tissue disorders that are associated with scleral disease. Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common. It may also be infectious or induced surgically or traumatically. There is no known HLA association.

Risk Factors

As scleritis is associated with systemic autoimmune diseases, it is more common in women. It usually occurs in the fourth to sixth decades of life. Men are more likely to have infectious scleritis than women. Patients with a history of pterygium surgery with adjunctive mitomycin C administration or beta irradiation are at higher risk of infectious scleritis due to defects in the overlying conjunctiva from calcific plaque formation and scleral necrosis. Bilateral scleritis is more often seen in patients with rheumatic disease. Two or more surgical procedures may be associated with the onset of surgically induced scleritis.

General Pathology

Histologically, the appearance of episcleritis and scleritis differs in that the sclera is not involved in the former. In episcleritis, hyperemia, edema and infiltration of the superficial tissue is noted, along with dilated and congested vascular networks. There is chronic, nongranulomatous infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

In scleritis, scleral edema and inflammation are present in all forms of disease. There is often a zonal granulomatous reaction that may be localized or diffuse. If localized, it may result in near total loss of scleral tissue in that region. Most commonly, the inflammation begins in one area and spreads circumferentially until the entire anterior segment is involved.

Inflammation of the sclera can involve a nongranulomatous process (lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages) or a granulomatous process (epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells) with or without associated scleral necrosis.

Pathophysiology

As there are different forms of scleritis, the pathophysiology is also varied. Scleritis associated with autoimmune disease is characterized by zonal necrosis of the sclera, surrounded by granulomatous inflammation and vasculitis. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material may be found at the center of the granuloma. These eyes may exhibit vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis and neutrophil invasion of the vessel wall.

There is an increase in inflammatory cells including T-cells of all types and macrophages. T-cells and macrophages tend to infiltrate the deep episcleral tissue with clusters of B-cells in perivascular areas. There may be cell-mediated immune response, as there is increased HLA-DR expression, as well as increased IL-2 receptor expression, on the T-cells. Plasma cells may be involved in the production of matrix metalloproteinases and TNF-alpha. In idiopathic necrotizing scleritis, there may be small foci of scleral necrosis and mainly nongranulomatous inflammation with mainly mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages). Microabscesses may be found in addition to necrotizing inflammation in infectious scleritis.

Vasculitis is not prominent in nonnecrotizing scleritis.

Diagnosis

History

The onset of scleritis is gradual. Most patients develop severe boring or piercing eye pain over several days. Globe tenderness and redness may involve the whole eye or a small localized area.

Physical Examination

Scleritis presents with a characteristic violet-bluish hue with scleral edema and dilatation. Examination in natural light is useful in differentiating the subtle color differences between scleritis and episcleritis. On slit-lamp biomicroscopy, inflamed scleral vessels often have a criss-crossed pattern and are adherent to the sclera. They cannot be moved with a cotton-tipped applicator, which differentiates inflamed scleral vessels from more superficial episcleral vessels. Red-free light with the slit lamp also accentuates the visibility of the blood vessels and areas of capillary nonperfusion. Finally, the conjunctival and superficial vessels may blanch with 2.5%-10% phenylephrine, but deep vessels are not affected. The globe is also often tender to touch.

Signs

Scleritis presents with a characteristic violet-bluish hue with scleral edema and dilatation. Other signs vary, depending on the location of the scleritis and degree of involvement. In the anterior segment there may be associated keratitis with corneal infiltrates or thinning, uveitis, and trabeculitis. With posterior scleritis, there may be chorioretinal granulomas, retinal vasculitis, serous retinal detachment, and optic nerve edema with or without cotton-wool spots.

Non-ocular signs are important in the evaluation of the many systemic associations of scleritis. epistaxis, sinusitis, and hemoptysis are present in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis). Arthritis with skin nodules, pericarditis, and anemia are features of rheumatoid arthritis. Systemic lupus erythematous may present with a malar rash, photosensitivity, pleuritis, pericarditis, and seizures. In addition to scleritis, myalgias, weight loss, fever, purpura, nephropathy, and hypertension may be signs of polyarteritis nodosa.

Symptoms

A severe pain that may involve the eye and orbit is usually present. This pain is characteristically dull and boring in nature and exacerbated by eye movements. Worsening of the pain during eye movement is due to the extraocular muscle insertions into the sclera. It may be worse at night and awakens the patient while sleeping. This pain may radiate to involve the ear, scalp, face, and jaw.

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis of scleritis is clinical. However, laboratory testing is often necessary to discover any associated connective tissue and autoimmune disease.

Diagnostic procedures

B-scan ultrasonography and orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used for the detection of posterior scleritis. Ultrasonographic changes include scleral and choroidal thickening, scleral nodules, distended optic nerve sheath, fluid in Tenons capsule, or retinal detachment.

Laboratory testing

As scleritis may occur in association with many systemic diseases, laboratory workup may be extensive. As mentioned earlier, the autoimmune connective tissue diseases of rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, sero-negative spondylarthropathies and vasculitides such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis and polyarteritis nodosa are most frequently seen. In addition to complete physical examination, laboratory studies should include assessment of blood pressure, renal function, and acute-phase response. Laboratory tests include complete blood cell (CBC) count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP), serum autoantibody screen (including antinuclear antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies), urinalysis, syphilis serology, serum uric acid, and sarcoidosis screening.

Differential diagnosis

Episcleritis is defined as inflammation confined to the more superficial episcleral tissue. Episcleritis is usually idiopathic and non-vision threatening, without involvement of adjacent tissues. Vessels have a reddish hue compared to the deeper-bluish hue in scleritis. These superficial vessels blanch with 2.5%-10% phenylephrine, while deeper vessels are unaffected.

Management

General treatment

The primary goal of treatment of scleritis is to minimize inflammation and thus reduce damage to ocular structures.

Medical therapy

NSAIDS

Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first-line agent for mild-to-moderate scleritis. These consist of nonselective or selective cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (COX inhibitors). Nonselective COX-inhibitors such as flurbiprofen, indomethacin, and ibuprofen may be used. Indomethacin 50 mg 3 times a day or 600 mg of ibuprofen 3 times a day may be used. Patients using oral NSAIDS should be warned of the gastrointestinal (GI) side effects, including gastric bleeding. Patients with renal compromise must be warned of renal toxicity. NSAIDS that are selective COX-2 inhibitors may have fewer GI side effects, but they may have more cardiovascular side effects.

Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids may reduce ocular inflammation, but treatment is generally systemic. Corticosteroids may be used in patients unresponsive to COX-inhibitors or those with posterior or necrotizing disease. A typical starting dose may be 1 mg/kg/day of prednisone. This dose should be tapered to the best-tolerated dose. Pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone at 0.5 g-1 g may be required initially for severe scleritis. Side effects of steroids that patients should be made aware of include elevated intraocular pressure, decreased resistance to infection, gastric irritation, osteoporosis, weight gain, hyperglycemia, and mood changes.

Immunomodulatory agents

If the disease is inadequately controlled on corticosteroids, immunomodulatory therapy may be necessary. Likewise, immunomodulatory agents should be considered in those who might otherwise be on chronic steroid use. Consultation with a rheumatologist or other internist is recommended. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may be prescribed methotrexate. Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis may require cyclosphosphamide or mycophenolate. Cyclosporine is nephrotoxic and thus may be used as adjunct therapy, allowing for lower corticosteroid dosing. Mycophenolate mofetil may eliminate the need for corticosteroids. However, there is a risk of hematologic and hepatic toxicity.

More recently, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitors such as infliximab have shown promise in the treatment of noninfectious scleritis refractory to other treatment. Treatment consists of repeated infusions as the treatment effect is short-lived. TNF-alpha inhibitors may also result in a drug-induced, lupus-like syndrome, as well as increased risk of lymphoproliferative disease. All patients on immunomodulatory therapy must be closely monitored for development of systemic complications with these medications.

Medical follow up

Adjustment of medications and dosages is based on the level of clinical response. Laboratory testing may be ordered regularly to follow the therapeutic levels of the medication, to monitor for systemic toxicity, or to determine treatment efficacy.

Surgery

Clinical examination is usually sufficient for diagnosis. Formal biopsy may be performed to exclude a neoplastic or infective cause. However, one must be prepared to place a scleral reinforcement graft or other patch graft, as severe thinning may result in the presentation of intraocular contents. Small corneal perforations may be treated with bandage contact lens or corneal glue until inflammation is adequately controlled, allowing for surgery.

Primary indications for surgical intervention include scleral perforation or the presence of excessive scleral thinning with a high risk of rupture. High-grade astigmatism caused by staphyloma formation may also be treated. Reinforcement of the sclera may be achieved with preserved donor sclera, periosteum, or fascia lata. A lamellar or perforating keratoplasty may be necessary. Cataract surgery should only be performed when the scleritis has been in remission for 2-3 months. Small-incision clear corneal surgery is preferred, and one must anticipate a return of inflammation in the postsurgical period.

Surgical follow up

Surgical biopsy of the sclera should be avoided in active disease, though if absolutely necessary, the surgeon should be prepared to bolster the affected tissue with either fresh or banked tissue (ie, preserved pericardium, banked sclera, or fascia lata). Areas with imminent scleral perforation warrant surgical intervention, though the majority of patients often have scleral thinning or staphyloma formation that do not require scleral reinforcement.

Complications

Complications are frequent and include peripheral keratitis, uveitis, cataract, and glaucoma. Central stromal keratitis may also occur in the absence of treatment. Sclerokeratitis in which peripheral cornea is opacified by fibrosis and lipid deposition with neighboring scleritis may occur, particularly with herpes zoster scleritis. Sclerosing keratitis may present with crystalline deposits in the posterior corneal lamellae. Sclerokeratitis may move centrally gradually and thus opacify a large segment of the cornea. Vitritis (cells and debris in vitreous) and exudative detachments occur in posterior scleritis.

Prognosis

Visual loss is related to the severity of the scleritis. Patients with mild or moderate scleritis usually maintain excellent vision. Scleritis may be active for several months or years before going into long-term remission. Patients with necrotizing scleritis have a high incidence of visual loss and an increased mortality rate.

Additional Resources

References

- Akpek EK, Thorne JE, Qazi FA, Do DV, Jabs DA. Evaluation of patients with scleritis for systemic disease. Ophthalmology. 2004 Mar;111(3):501-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.006. PMID: 15019326.

- Okhravi N, Odufuwa B, McCluskey P, Lightman S. Scleritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005 Jul-Aug;50(4):351-63. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.04.001. PMID: 15967190.

- Riono WP, Hidayat AA, Rao NA. Scleritis: a clinicopathologic study of 55 cases. Ophthalmology. 1999 Jul;106(7):1328-33. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00719-8. PMID: 10406616.

- Yanoff M, Duker JS. Episcleritis and Scleritis in Elsevier: Ophthalmology. 2008. Chapter 4.11: 255-261.