Retinocytoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

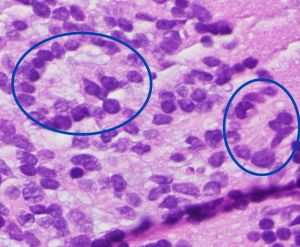

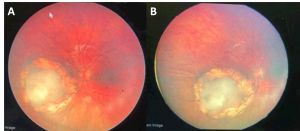

Retinocytoma is a rare benign intraocular tumor of the retinal progenitor cells and is considered a variant of retinoblastoma. The tumor is characterized by its translucent gray color, intralesional calcifications, and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) alterations (Figure 1). Although retinocytomas typically have favorable prognosis, retinocytomas require lifelong monitoring due to the potential for malignant transformation into retinoblastoma.

Retinocytoma is not specifically listed in the International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10) but can be classified under the following:

- D31.2 Benign neoplasm of unspecified retina

Epidemiology

In the United States, the incidence of retinoblastoma is 11.8 cases per million, and retinocytoma accounts for 1.8-10% of retinoblastoma cases. However, the prevalence may be higher given that retinocytomas are often asymptomatic and underdiagnosed.[1][2]

History

In 1977, Gallie et al. observed that 1% of retinoblastomas undergo “spontaneous regression” and named these tumors “retinomas” due to their benign behavior.[3][4] In 1983, Margo et al. found that retinomas in enucleated eyes have well-differentiated and benign-appearing photoreceptor “fleurettes” without mitosis or necrosis. They introduced the term “retinocytoma” to align with naming conventions of neurogenic tumors such as pineoblastoma and pineocytoma.[5]

Pathophysiology

Like retinoblastoma, retinocytoma develops after biallelic inactivation of the RB1 tumor suppressor gene in chromosome 13q14 in accordance with the Knudson two-hit hypothesis. The first “hit” may be inherited or acquired in early embryonic development, and the second “hit” occurs after a somatic RB1 mutation.

Even though both retinoblastoma and retinocytoma share genetic origin, some individuals develop retinocytoma rather than retinoblastoma. One hypothesis is that the second “hit” in retinocytoma may occur later in development when retinal cells have minimal mitotic potential. Another hypothesis is that retinocytoma may develop as a result of low penetrance of the RB1 mutation.[2][4]

Retinocytoma rarely undergo malignant transformation into retinoblastoma. A study by Dimaras et al. observed low genomic instability in retinocytomas, suggesting that malignant transformation to retinoblastoma could occur with genomic instability and reduced expression of senescence-associated proteins.[6]

General Pathology

Histologically, retinocytoma is characterized by bland round oval nuclei with evenly dispersed chromatin and clear cytoplasm in addition to scattered fleurettes from photoreceptor differentiation (Figure 2). On immunohistochemistry, retinocytomas are generally positive for anti-RB antibodies, retinal S antigen, S-100 protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). In contrast, retinoblastomas have malignant features of pleomorphism, mitosis, and necrosis in addition to Homer-Wright and Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes.[5][7]

Diagnosis

History

Most patients with retinoctyoma are asymptomatic. They can be diagnosed incidentally on routine eye exam or on screening after a family member is diagnosed with retinoblastoma. Retinocytoma is generally diagnosed after age 6 in contrast to retinoblastoma, which is usually diagnosed under age 5. Median age of diagnosis is 15 years with age range of 4-45 years.[1][2]

Symptoms

The typical symptoms are:

- Asymptomatic

- Decreased vision

- Strabismus

- Floaters

- Flashes

Fundus Examination

Characteristic features (Figure 1) include:

- Translucent grayish retinal mass (88%)

- Intralesional calcification (63%)

- RPE alterations (54%)

Presence of at least 2 features is seen in 71% of tumors. Chorioretinal atrophy is seen in 54% of tumors and is reminiscent of regressing retinoblastoma after radiation. Retinal feeder vessels have normal caliber and can be tortuous. Retinocytoma can occur with retinoblastoma in the same or fellow eye. The tumor is commonly unilateral, but 13% can be bilateral.

Malignant transformation to retinoblastoma should be suspected if there is vitreous seeding, dilated tortuous feeder vessels, and rapid growth across multiple visits.[2][7]

Diagnostic Procedures

Ancillary testing may assist in diagnosis and monitoring.

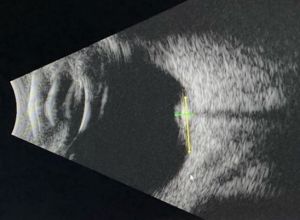

B Scan Ultrasonography

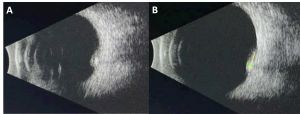

B scan can help assess tumor size and intralesional calcifications (Figure 3). Typical features are:

- High internal reflectivity

- Shadowing from intralesional calcifications

- Clear vitreous

- Typical dimensions: 6.0-6.25 mm base, 1.75-2.3 mm height[1][2][8]

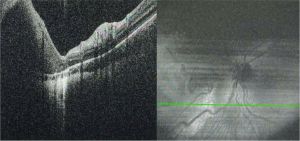

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

Typical features on OCT include (Figure 4):

- Hyperreflective inner layer with choroidal shadowing

- RPE and outer retinal disruption

- Chorioretinal atrophy in surrounding tissue[7]

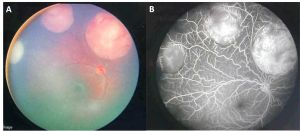

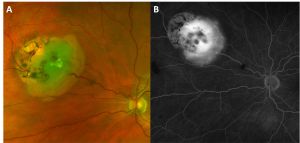

Fluorescein Angiography (FA)

Typical features on FA include (Figure 5):

- Normal caliber of feeder vessels

- Mildly tortuous feeder vessels

- Minimal or absent dye leakage

- Window defect at area of chorioretinal atrophy

This is in contrast to retinoblastoma in which the feeder vessels are dilated and form complex intratumoral vascular network with dye leakage (Figure 6).[7]

Biopsy

Retinocytomas are often diagnosed on clinical examination and rarely require biopsy. Berry et al. have utilized aqueous humor liquid biopsy with LBSEQ4KIDS to determine presence of tumor DNA and exclude retinoblastoma, which can be useful if clinical examination is inconclusive. [9][10][11][12][13][14]

Differential Diagnoses

- Retinoblastoma. See Table 1 for distinguishing features of retinocytoma and retinoblastoma.

- Retinal astrocytic hamartoma: Astrocytic hamartoma is commonly associated with tuberous sclerosis. Unlike retinocytoma, astrocytic hamartomas lack chorioretinal atrophy, RPE changes, and feeder vessels.

- Congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE): Like retinocytoma, CHRPE is a well-defined retinal lesion. However, CHRPE does not have calcifications, chorioretinal atrophy, and feeder vessels.[7]

| Table 1: Comparison of retinocytoma and retinoblastoma features | ||

| Retinocytoma | Retinoblastoma | |

| Median age of diagnosis | 5 years | 15 months |

| Genetics | RB1 mutation | RB1 mutation |

| Color | Translucent gray color | White or cream color |

| Intralesional calcification | Present | Present |

| Chorioretinal atrophy | Present | Rare at presentation |

| RPE changes | Present | Present |

| Vitreous seeding | Rare | Possible at later stages |

| Feeder Vessels | Normal course and caliber, possible mild tortuosity | Dilated, tortuous |

| Intralesional vessels | Rare | Present |

| Fluorescein angiography | Minimal or absent tumor dye leakage | Tumor dye staining and leakage |

| Pathology | Bland round oval nuclei, evenly dispersed chromatin, clear cytoplasm, fleurettes from photoreceptor differentiation | Pleomorphism, mitosis, and necrosis, Homer-Wright and Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes |

Management

General Management

The two main management options for retinocytomas are as follows:

- Observation for stable tumors

- Laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy for symptomatic cases or early malignant changes. Similar to laser treatment for retinoblastoma, an 810-nm diode laser with large-spot indirect ophthalmoscopy is used. Power and duration are titrated until gray-white lesions appear and surround the tumor.[15] The laser treatment should be repeated for continued slow and steady tumor regression (Figures 7 and 8).

Retinocytomas often remain stable but carry a 4-15.3% risk of malignant transformation by 10 years with a mean time to malignant transformation of 9.8 years. Malignant transformation was more frequent in tumors with increased thickness.[1] Signs of malignant transformation to retinoblastoma include (Figure 9):

- Vitreous seeding

- Dilated tortuous feeder vessels

- Intralesional vessels

- Rapid growth across multiple visits[2][7]

If malignant transformation is suspected, patients should be referred for appropriate retinoblastoma treatments.

Genetic Counseling

Diagnosis of retinocytoma suggests possible presence of germline RB1 pathogenic variant. Serum-based genetic testing is recommended for patient and if positive, family members. Patients with germline RB1 mutations are at an increased lifetime risk of secondary malignant neoplasms (most commonly osteosarcoma) and should be screened and followed appropriately.[1][2][7]

Follow Up

Patients should be monitored regularly to detect early malignant transformation. Patients should be monitored with fundoscopic exam, fundus photos, B scan ultrasonography, OCT, FA, and fundus autofluorescence to document any changes. Shields et al. recommend monthly follow up initially to ensure tumor stability, and then follow up can be extended to every 6 and then 12 months for life.[1]

Prognosis

Retinocytomas typically remain stable throughout life but should undergo lifelong monitoring due to the potential for malignant transformation.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Shields CL, Srinivasan A, Lucio-Alvarez JA, Shields JA. Retinocytoma/retinoma: comparative analysis of clinical features in 78 tumors and rate of transformation into retinoblastoma over 20 years. J AAPOS Off Publ Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2021;25(3):147.e1-147.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.11.024

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Singh AD, Santos CM, Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC. Observations on 17 patients with retinocytoma. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2000;118(2):199-205. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.2.199

- ↑ Gallie BL, Dupont B, Whitsett C, Kitchen FD, Ellsworth RM, Good RA. Histocompatibility typing in spontaneous regression of retinoblastoma. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1977;16:229-237.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gallie BL, Ellsworth RM, Abramson DH, Phillips RA. Retinoma: spontaneous regression of retinoblastoma or benign manifestation of the mutation? Br J Cancer. 1982;45(4):513-521. doi:10.1038/bjc.1982.87

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Margo C, Hidayat A, Kopelman J, Zimmerman LE. Retinocytoma. A benign variant of retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 1983;101(10):1519-1531. doi:10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020521003

- ↑ Dimaras H, Khetan V, Halliday W, et al. Loss of RB1 induces non-proliferative retinoma: increasing genomic instability correlates with progression to retinoblastoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(10):1363-1372. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn024

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Al-Hussaini M, Sharie SA, Sultan H, Mohammad M, Yousef YA. Retinocytoma: understanding pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment approaches. Int J Retina Vitr. 2025;11(1):20. doi:10.1186/s40942-025-00642-z

- ↑ Bubshait L, Alburayk K, Alabdulhadi H, Emara K. Retinocytoma: A Case Series. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e42958. doi:10.7759/cureus.42958

- ↑ Berry JL, Xu L, Polski A, et al. Aqueous Humor Is Superior to Blood as a Liquid Biopsy for Retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(4):552-554. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.10.026

- ↑ Berry JL, Pike S, Shah R, et al. Aqueous Humor Liquid Biopsy as a Companion Diagnostic for Retinoblastoma: Implications for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Options: Five Years of Progress. Am J Ophthalmol. 2024;263:188-205. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2023.11.020

- ↑ Berry JL, Xu L, Murphree AL, et al. Potential of Aqueous Humor as a Surrogate Tumor Biopsy for Retinoblastoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(11):1221-1230. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.4097

- ↑ Chigane D, Pandya D, Singh M, et al. Safety Assessment of Aqueous Humor Liquid Biopsy in Retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. Published online March 2025:S0161642025001800. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2025.03.018

- ↑ Nelson AJ, Park S, Nelson MD, Berry JL. Aqueous Humor Liquid Biopsy to Exclude Retinoblastoma for a Child with an Intraocular Mass. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2025;16(1):366-371. doi:10.1159/000545924

- ↑ Sanchez GM, Chigane D, Lin M, Xu L, Yellapantula V, Berry JL. Retinoblastoma: Aqueous humor liquid biopsy. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2025;15(1):55-61. doi:10.4103/tjo.TJO-D-24-00133

- ↑ Lee TC, Lee SW, Dinkin MJ, Ober MD, Beaverson KL, Abramson DH. Chorioretinal scar growth after 810-nanometer laser treatment for retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(5):992-996. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.08.036