Retinal Vasculitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Retinal vasculitis is recognized by the following codes as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 nomenclature:

- Diagnosis Codes

- H35.061 Retinal Vasculitis, right eye

- H35.062 Retinal Vasculitis, left eye

- H35.063 Retinal Vasculitis, bilateral

- H35.069 Retinal Vasculitis, unspecified eye

Disease

Retinal vasculitis can be an isolated condition or a complication of local or systemic inflammatory disorders characterized by inflammation of the retinal vessels. It is a sight-threatening condition associated with various infective, autoimmune, inflammatory, and neoplastic disorders.

History

The concept of retinal vessel inflammation was introduced by John Hunter (Figure 1) in 1784, in his report "Observations on the Inflammation of the Internal Coats of the Veins."[1] Since then, various epidemiologic, imaging, and clinicopathologic studies have been conducted to improve the understanding of this condition. Initially, retinal vasculitis was thought to be an extension of the systemic disease.[2] However, because of the unique microstructure of the retinal vessels, there are major differences between retinal and systemic vasculitis; for example, unlike systemic vasculitis, retinal vasculitis is not associated with vascular necrosis.[3]

Definitions

Retinal vasculitis is used as a descriptive term to explain a conglomerate of typical clinical manifestations, including perivascular sheathing or cuffing, vascular leakage, and/or occlusion.[4][5] It may be associated with signs of retinal ischemia, including cotton-wool spots and intraretinal hemorrhage. Involvement of retinal veins due to inflammation called phlebitis, whereas retinal arteriolar involvement is called arteriolitis.[6]

Epidemiology

Retinal vasculitis may be associated with a number of systemic and local diseases (Table 1).[7][8] Rarely, it may be an isolated, idiopathic condition, known as as idiopathic retinal vasculitis. It may also present as an initial manifestation of an underlying disorder. Isolated retinal vasculitis is seen in approximately 3% of cases diagnosed with uveitis.[9]

The annual incidence rate of retinal vasculitis is 1–2 per 10,000.[10] In one case series, approximately 55% of patients with retinal vasculitis had associated systemic inflammatory disease.[1][11] In a larger case series involving more than 1300 patients, retinal vasculitis was seen in approximately 15% of patients with uveitis, while systemic vasculitis was associated with retinal vasculitis in only 1.4% of cases.[3]

Retinal vasculitis appears to be more common in younger adults (aged <40 years), with a slight preponderance in women.[1][9] In one study, the mean age of retinal vasculitis diagnosis was 34 years.[2]

This disease is usually bilateral and is often vision threatening. As many as one-third of patients with retinal vasculitis may suffer from severe visual loss (<20/200).[12][13]

Classification

Systemic vasculitis was classified by the 2012 International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Vasculitides, according to the location of vessel involvement[14]:

- Predominantly involved vessels

- Artery: Acute retinal necrosis, idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysm and neuroretinitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa, syphilis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome

- Vein: Eales disease, intermediate uveitis, sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, tuberculosis, birdshot chorioretinitis, and HIV paraviral syndrome

- Both artery and vein: Frosted branch angiitis, toxoplasmosis, relapsing polychondritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener's granulomatosis), and Crohn's disease

- Involvement of peripheral vessels or vessels around the posterior pole

Stages of Retinal Vasculitis

Retinal vasculitis is staged based on the following:

- Inflammation: This denotes active inflammation and is clinically denoted by perivascular segmental whitish infiltrates with fuzzy borders (cuffing), retinal edema, retinal hemorrhages, cystoid macular edema, snow balls in the vitreous (in some cases), and inflammatory vascular occlusions (the blockage of veins at the area of active vasculitis, which may not correspond to the arteriovenous junction). Active choroiditis (e.g., birdshot chorioretinitis), retinitis (e.g., cytomegaloviral retinitis), intermediate uveitis, and anterior uveitis (panuveitis ) may also be seen. The ocular disease or systemic disease causing the retinal vasculitis should be treated as per protocol. Infectious causes should be ruled out and treated as necessary. Unilateral noninfectious retinal vasculitis involving the posterior pole, causing cystoid macular edema or visual decline, is treated with periocular steroids (posterior Sub-tenon triamcinolone, pulse steroid therapy [PST], or intravitreal triamcinolone) after ruling out glaucoma or steroid response. Oral steroids also remain an option in cases where periocular steroids are contraindicated. The role of systemic or local steroids in peripheral noninfectious vasculitis not involving the macula is controversial. Bilateral active noninfectious retinal vasculitis involving the macula may be treated with oral steroids (after ruling out infection) or sequential PST.

- Ischemia: Clinically characterized by sclerosed vessels and tortuous collaterals. Healed paravascular pigmented choroiditic patches may be seen. Fluorescein angiography shows retinal capillary nonperfusion (CNP), though neovascularization is not seen. Most ophthalmologists will follow up such cases. The collaterals should not be lasered, as it may denote a healing response to revascularize the area which suffered ischemia due to inflammatory retinal venous occlusion

- Neovascularization: This stage most commonly presents with vitreous hemorrhage. Laser of the CNP area, as denoted by fluorescein angiography, is the treatment of choice

- Stage of complications: Complications include nonresolving vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, combined rhegmatogenous and tractional retinal detachment, epiretinal membrane, neovascular glaucoma, and neovascularization of the iris. Vitrectomy and filtration surgery are some of the treatment options

Pathophysiology

Despite precise clinical visualization of the retinal microvasculature, the exact pathophysiologic mechanism of this condition is not clear.[2][5][6] Experimental animal models have been created to better understand pathogenesis of retinal vasculitis in humans.[15] The manifestations of vascular sheathing and cuffing led to the belief that retinal vasculitis results from a type III hypersensitivity reaction[16]; however, this hypothesis was not supported by animal or human models.[17] A breakdown of the blood–retina barrier secondary to intraocular or systemic inflammation is more likely. Due to the characteristic perivascular location of the inflammation, terms such as perivasculitis and periphlebitis have been suggested to denote the underlying pathology.[6]

Studies have demonstrated the presence of focal, segmental, or diffuse retinal perivascular proliferation of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates in eyes with retinal vasculitis.[18] In granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis, there may be a collection of numerous epithelioid cells. In eyes with intermediate uveitis and retinal vasculitis secondary to primary vitreoretinal lymphoma, histopathologic studies noted lymphocytic cuffing with mural involvement of retinal veins.[19] Characterization of lymphocytic cells in the perivascular region revealed the predominance of CD4+ T cells, rather than CD8+ T cells or B lymphocytes.[10][20] There is also an upregulation of various inflammatory cellular markers, including integrins and cell adhesion molecules.[21][22][23] Increased expression of cell adhesion molecules along retinal vessels, and blood–retina barrier cells may play an important role in inflammatory cell recruitment. The sera of patients with retinal vasculitis often show an increase in the levels of type 1 interferons (e.g., interferon-β). Other molecules that are upregulated include E-selectin and s-intracellular adhesion molecules.[24]

Although there is a large pathologic diversity among the retinal vasculitis etiologies, inflammatory changes manifest similarly in many ways. In patients with infective retinal vasculitis, culture of live organisms such as mycobacteria may be possible from various systemic foci.[25] Organisms can infect the retinal vasculature by various mechanisms, apart from direct vascular endothelial injury, and can cause toxin release and the upregulation of molecules such as heat-shock proteins.[26] Molecular mimicry may result in aberrant activation of immunologic pathways, resulting in pathologic manifestations.[10]

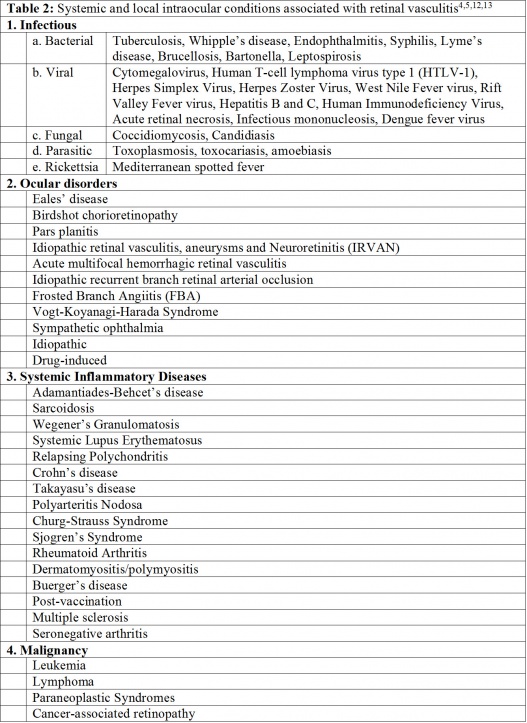

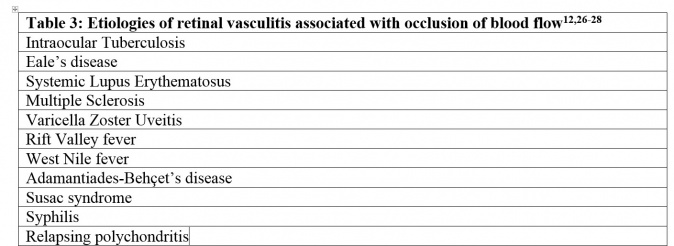

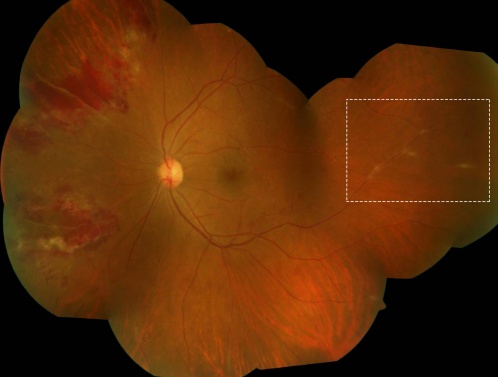

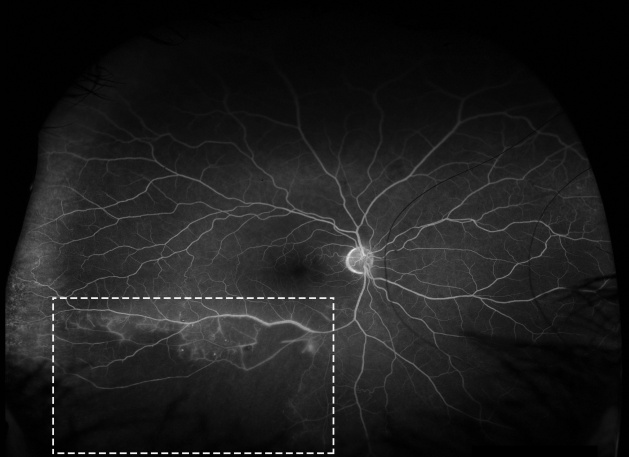

In some patients with retinal vasculitis, there is occlusion of blood flow through the retinal vessels. The pathology of occlusive retinal vasculitis may be distinct from vasculitis without evidence of obliteration of blood flow. Evidence suggests that eyes with occlusive vasculitis have a poorer prognosis, with a higher number of complications such as cystoid macular edema, neovascularization, and epiretinal membrane formation. A case of retinal occlusive vasculitis seen on fluorescein angiography is shown in Figure 2. Various etiologies associated with occlusive vasculitis are listed in Table 2.[27][28][29]

Diagnosis

History

Retinal vasculitis can affect individuals of any age, sex, race, or ethnicity. However, those with idiopathic retinal vasculitis are typically young adults without any signs or symptoms of underlying ocular or systemic disease.[2]

Physical Examination

Examination of patients with retinal vasculitis is performed using both slit-lamp biomicroscopy with 90- or 78-D lenses and indirect ophthalmoscopy with either 20- or 28-D lenses. The location of the vasculitis may be in the posterior pole or far periphery; hence, scleral indentation must be performed to carefully examine the pars plana and ora serrata.

Signs

Retinal vasculitis presents with characteristic features on clinical examination. The area of vascular involvement can be focal, diffuse, or segmental. Often, retinal vasculitis may involve the veins alone.[7] Retinal arteritis is more common with diseases such as acute retinal necrosis and systemic vasculitidis.[30] There are various manifestations of retinal vasculitis, as listed below.

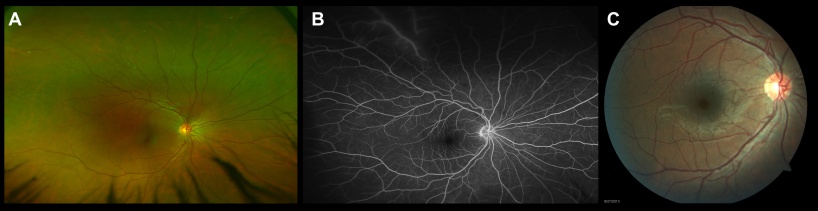

Perivascular Sheathing

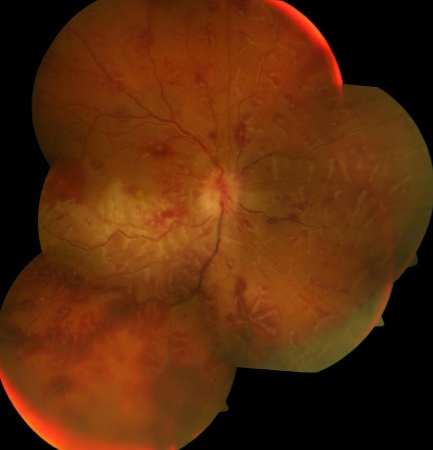

The classic feature of retinal vasculitis is the presence of sheathing around the vessel wall. The perivascular sheathing is a collection of exudations consisting of inflammatory cells around the affected vessels. This results in appearance of a white cuff around the blood vessels. Retinal vascular sheathing is often seen in certain diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and Eales disease.[31][32] Sarcoidosis can be associated with exuberant retinal perivascular infiltrates that give an impression of "candle-wax drippings."[33] Vascular sheathing secondary to intraocular tuberculosis is depicted in Figure 3.

Intraretinal Infiltrates

Patches of retinitis may accompany retinal vasculitis, especially in patients with Adamantiades-Behçet disease (ABD)[34] or infectious uveitis.[35] These patches of retinitis may be transient, as in ABD, or accompanied by retinal necrosis. Intraretinal infiltrates can be sight-threatening and can lead to retinal atrophy, breaks, and detachment. Cytomegalovirus retinitis associated with retinal vasculitis is shown in Figure 4.

Cotton-Wool Spots

Retinal vasculitis may result in microinfarcts of the retinal nerve fiber layer that manifest as diffuse, fluffy, cotton-wool–like spots in the superficial retinal surface.[1][7] Systemic vasculitides such as systemic lupus erythematosus,[36] polyarteritis nodosa,[37] and Churg-Strauss syndrome[38] can be associated with retinal precapillary arteriolar occlusion, resulting in cotton-wool spots. An increase in the number of cotton-wool spots may signify a uveitis flareup.

Retinal Necrosis

Necrosis of the retinal layers may occur with infectious forms of uveitis associated with retinal vasculitis. It is commonly seen in patients with toxoplasmosis,[39] viral infections such as varicella zoster[40] or herpes simplex,[41] cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis,[42] and human T-cell lymphoma virus type 1.[43] Toxoplasmosis can also cause reactivation of the retinal lesion adjacent to a previous scar. Kyrieleis arteriolitis[44] is an accumulation of periarteriolar exudates in eyes with toxoplasmosis leading to retinal necrosis (Figure 5). Foci of chorioretinitis and choroiditis may be closely associated with retinal vasculitis. Chorioretinal lesions in cytomegalovirus retinitis give an appearance of pizza-pie retinopathy.

Frosted Branch Angiitis

Frosted branch angiitis is a descriptive term for retinal vasculitis characterized by severe infiltration of perivascular space with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates,[45] giving the appearance of frosted branches of a tree. This condition can be associated with lymphoproliferative diseases such as lymphoma or leukemia (Figure 6),[46] due to accumulation of malignant cells. However, frosted branch angiitis has also been reported in systemic lupus erythematosus,[47] Crohn’s disease,[48] toxoplasmosis,[49] and AIDS.[50]

Retinal Ischemia

Occlusion of retinal vasculature secondary to inflammation may result in ischemia of the retina and development of capillary nonperfusion areas (Figure 2). Patients with retinal ischemia may be predisposed to develop complications arising out of this retinal nonperfusion, such as neovascularization and intraocular hemorrhage. Retinal ischemia is commonly seen following tuberculosis[51] or systemic lupus erythematosus.[52] Inflammatory branch retinal artery occlusion may be seen in patients with ABD.[53] Retinal vasculitis may be associated with sclerosis and attenuation of the vessel wall, leading to development of a significant area of retinal nonperfusion. Other complications that can result from retinal ischemia include rubeosis, tractional retinal detachment, and recurrent vitreous hemorrhage.

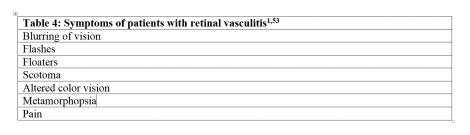

Symptoms

Table 3 lists some of the symptoms of retinal vasculitis.[1][54]

Clinical Diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis of retinal vasculitis is supported by ancillary tests, including fluorescein angiography. The signs of retinal vasculitis on fundus examination are protean.

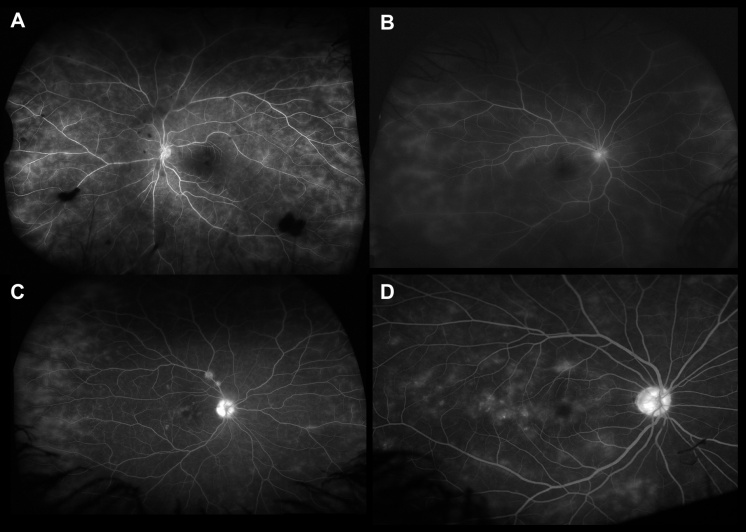

Fluorescein Angiography Findings

Fluorescein angiography is routinely used in the diagnosis, monitoring and management of patients with retinal vasculitis.[54] Signs on fluorescein angiography, such as vascular leakage and macular edema, can help assess the activity of the disease. Leakage of dye from vascular compartments results in perivascular hyperfluorescence. Normal retinal vascular flow and fluorescence is demonstrated in the video below.

The findings of retinal vasculitis on fluorescein angiography are summarized in Figure 8.

Vascular Leakage

Due to inflammation and breakdown of the blood-retinal-barrier, fluorescein angiography in eyes with retinal vasculitis can reveal diffuse, segmental, or focal vascular leakage. In addition, there may be evidence of capillary dropout due to occlusion of blood flow (Figure 2). This can lead to growth of new, leaky vessels. The pattern of leakage may vary depending upon the etiology. While venular leakage is the more common pattern of retinal vasculitis,[54] in cases of systemic vasculitis or viral infections the leakage may limited to arterioles. Often, the vascular leakage may be peripheral. Conventional fundus cameras can capture only the central 30° or 50° field of view, but ultrawide field imaging of the fundus allows the clinician to obtain more information (Figure 7). One study found that the use of ultrawide field imaging can potentially alter decision-making in more than half of patients with retinal vasculitis.[55]

Capillary Nonperfusion

Retinal ischemia is a feature of a subset of patients with retinal vasculitis. This presents on fluorescein angiography as areas of capillary dropout. Behçet disease is characterized by ischemic branch vascular occlusion.[56] The areas of nonperfusion may be in the periphery or in the macula. Macular ischemia results in poorer visual outcome despite successful control of inflammation.

Retinal Neovascularization

Retinal ischemia and inflammation can lead to release of vascular endothelial growth factor that stimulates new vessel proliferation. New vessels are found at the optic disc or elsewhere on the retina. Patients with extensive retinal ischemia and capillary nonperfusion may require scatter laser photocoagulation.

Macular Edema

Patients with active retinal vasculitis may have reduced visual acuity due to the presence of macular edema. Retinal thickening can be observed on fluorescein angiography as leakage of dye in the macula or the presence of a diffuse hyperfluorescence increasing towards the late phase. There may be an increased macular leakage following laser photocoagulation performed for retinal ischemia.

Optic Nerve Head Inflammation

Retinal vasculitis may be associated with optic nerve head hyperfluorescence (Figure 8C). There may be staining of the optic nerve head in the late frame. This must be differentiated from optic nerve head leakage secondary to neovascularization.

Choroidal Vascular Flow

Choroidal vascular flow can be imaged using indocyanine green angiography (ICG). Patients with retinal vasculitis may have an abnormal choroidal blood flow,[57] and ICG angiography can assist in imaging such abnormal choroidal flow patterns as choroidal neovascularization or retinochoroidal anastomosis.

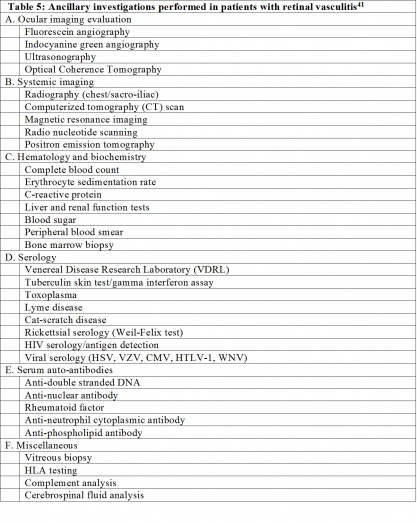

Laboratory Tests

A summary of diagnostic tests performed in patients with retinal vasculitis is listed in Table 4. Appropriate laboratory investigations aid in establishing the etiology for retinal vasculitis. A tailored approach to laboratory workup is preferred to avoid unnecessary investigations and expenses to the patient,[58] and should be based on systemic symptoms and signs, ocular examination, and a detailed patient history. The aim of laboratory workup is to identify infectious, noninfectious, or immunologic causes, as the treatment for each category may be different. In the absence of any laboratory positive result, malignancy should be kept in mind as one of the differential diagnoses.

Commonly performed laboratory evaluations include those which check for markers of systemic inflammation, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein. Based on the clinical features, infectious etiologies can be ruled out by performing specific investigations. Tuberculosis testing can be performed using the Mantoux test (tuberculin skin test); results are negative in cases of sarcoidosis. Chest x-ray and computed tomography can be performed to establish the etiology in cases where the diagnosis is challenging. Polymerase chain reaction has a higher sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis and can be very useful in patients with retinal vasculitis.

In patients where co-existent systemic vasculitis is possible, investigations can include testing for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies, anti-nuclear antibodies, and rheumatoid factor. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) testing can help identify diseases such as ABD (HLA-B5), birdshot chorioretinitis (HLA-A29), and systemic lupus erythematosus (HLA-DR3).

Laboratory testing for patients without evidence of systemic or ocular disease (idiopathic retinal vasculitis) can be limited to fluorescein angiography, complete blood counts, syphilis serology, ESR, urine analysis, tuberculin and HIV testing, and chest radiographs.[7]

Disease Monitoring

Patients with retinal vasculitis must be periodically examined to evaluate the extent and severity of vascular leakage.[59] The disease course can be effectively monitored with fluorescein angiography. Wide-field techniques assist the clinician in assessing peripheral vascular lesions and aid in guiding further therapy. Infectious retinal vasculitis can be monitored by determining the load of the causative organisms, using techniques such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction.[60][61][62] As retinal vasculitis may be an early manifestation of generalized vasculitis of the central nervous system (CNS), one needs to remember to evaluate and monitor the CNS vasculature (i.e., employing magnetic resonance imaging with contrast) as well.[63]

Management

The management of retinal vasculitis depends on the underlying etiology. Adequate control of the intraocular inflammation is important for achieving disease remission, as retinal vasculitis can be recurrent and aggressive, requiring steroid and immunosuppressive therapy.[6] Ocular sequelae resulting from uncontrolled retinal vasculitis can have deleterious consequences, including severe visual loss.

The mainstay of therapy for retinal vasculitis is medical management. Infectious etiology must be ruled out, as immunosuppressive therapy is used to treat noninfectious disease but can possibly worsen intraocular infections.

Medical Therapy

Noninfectious retinal vasculitis is managed by systemic or local corticosteroids and steroid-sparing immunosuppressants. The local delivery of therapeutic agents can be done via intravitreal injections or periocularly, although the latter may not be sufficient in cases of severe retinal vasculitis. The choice of immunosuppressants is determined by ocular manifestations, etiologies, and systemic comorbidities.

A case series of 56 patients with noninfectious uveitis revealed that systemic prednisone (oral) was used for the treatment of two-thirds of patients, at an average dose of 27 mg/day for a mean of 14 months.[1] Another study from India revealed that oral steroids were used in more than 80% patients with retinal vasculitis.[64] In addition, periocular and intraocular steroids such as triamcinolone have been used in vasculitis associated with pars planitis.[65][66][67] However, administration of steroid-sparing immunosuppressants is recommended in cases when oral prednisone at doses of >10 mg/day are needed.[68]

Unlike systemic vasculitis that can be managed with colchicines and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, retinal vasculitis due to causes such as ABD requires a more aggressive approach.[69] Available immunosuppressive agents include cyclosporine, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and mycophenolate mofetil, as well as biologic agents such as infliximab or etanercept. Cyclosporine has also been studied.[70][71] In eyes with vasculitis associated with birdshot chorioretinopathy, sarcoidosis, or Harada’s disease, azathioprine has been used for treatment.[72][73][74] Alkylating agents such as chlorambucil and cyclophosphamide may be given in combination with corticosteroids.[1] Biologic agents, including infliximab, tacrolimus and adalimumab as well as agents targeting interleukins and tumor necrosis factor, have been increasingly used to achieve remission in eyes with retinal vasculitis.[75]

Infectious retinal vasculitis must be treated with appropriate antimicrobial agents, as it can be caused by bacteria, viruses or parasites (Table 2).

Nonmedical Therapy

Panretinal photocoagulation has been studied for the control of retinal vasculitis,[6] Cryotherapy has been used in the past to treat retinal vasculitis associated with pars planitis.[76] While mesenchymal stem cell therapy has been studied in eyes in with ABD, so far it does not appear to show efficacy.[77]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Ali A, Ku JH, Suhler EB, et al. The course of retinal vasculitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(6):785-789.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 George RK, Walton RC, Whitcup SM, et al. Primary retinal vasculitis. Systemic associations and diagnostic evaluation. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(3):384-389.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rosenbaum JT, Ku J, Ali A, et al. Patients with retinal vasculitis rarely suffer from systemic vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(6):859-865.

- ↑ Walton RC, Ashmore ED. Retinal vasculitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14(6):413-419.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Abu El-Asrar AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. Retinal vasculitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13(6):415-433.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Levy-Clarke GA, Nussenblatt R. Retinal vasculitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45(2):99-113.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 El-Asrar AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. A clinical approach to the diagnosis of retinal vasculitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30(2):149-173.

- ↑ Abu El-Asrar AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. Differential diagnosis of retinal vasculitis. Middle East African J Ophthalmol. 2009;16(4):202-218.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Rodriguez A, Calonge M, Pedroza-Seres M, et al. Referral patterns of uveitis in a tertiary eye care center. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114(5):593-599.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hughes EH, Dick AD. The pathology and pathogenesis of retinal vasculitis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29(4):325-340.

- ↑ Graham EM, Stanford MR, Sanders MD, et al. A point prevalence study of 150 patients with idiopathic retinal vasculitis: 1. Diagnostic value of ophthalmological features. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73(9):714-721.

- ↑ Rothova A, Suttorp-van Schulten MS, Frits Treffers W, et al. Causes and frequency of blindness in patients with intraocular inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(4):332-336.

- ↑ Palmer HE, Stanford MR, Sanders MD, et al. Visual outcome of patients with idiopathic ischaemic and non-ischaemic retinal vasculitis. Eye (London). 1996;10(pt 3):343-348.

- ↑ Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17(5):603-606.

- ↑ Stanford MR, Graham EM, Kasp E, et al. Retinal vasculitis: correlation of animal and human disease. Eye (London). 1987;1(pt 1):69-77.

- ↑ Stubiger N, Winterhalter S, Pleyer U, et al. [Janus-faced?: Effects and side-effects of interferon therapy in ophthalmology]. [Article in German]. Ophthalmologe. 2011;108(3):204-212.

- ↑ Paović J, Paović P, Vukosavljević M. Clinical and immunological features of retinal vasculitis in systemic diseases. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2009;66(12):961-965.

- ↑ Axente D. [Retinal vasculitis]. [Article in Romanian] Oftalmologia. 2006;50(4):13-21.

- ↑ Velez G, Chan CC, Csaky KG. Fluorescein angiographic findings in primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 2002;22(1):37-43.

- ↑ Oh HM, Yu CR, Lee Y, et al. Autoreactive memory CD4+ T lymphocytes that mediate chronic uveitis reside in the bone marrow through STAT3-dependent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2011;187(6):3338-3346.

- ↑ Wallace GR, Farmer I, Church A, et al. Serum levels of chemokines correlate with disease activity in patients with retinal vasculitis. Immunol Lett. 2003;90(1):59-64.

- ↑ Kim WU, Do JH, Park KS, et al. Enhanced production of macrophage inhibitory protein-1alpha in patients with Behcet's disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34(2):129-135.

- ↑ Makhoul M, Dewispelaere R, Relvas LJ, et al. Characterization of retinal expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) during experimental autoimmune uveitis. Exp Eye Res. 2012;101:27-35.

- ↑ Lee MT, Hooper LC, Kump L, et al. Interferon-beta and adhesion molecules (E-selectin and s-intracellular adhesion molecule-1) are detected in sera from patients with retinal vasculitis and are induced in retinal vascular endothelial cells by Toll-like receptor 3 signalling. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147(1):71-80.

- ↑ Doycheva D, Pfannenberg C, Hetzel J, et al. Presumed tuberculosis-induced retinal vasculitis, diagnosed with positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT), aspiration biopsy, and culture. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18(3):194-199.

- ↑ Poulaki V, Iliaki E, Mitsiades N, et al. Inhibition of Hsp90 attenuates inflammation in endotoxin-induced uveitis. FASEB J. 2007;21(9):2113-2123.

- ↑ Narayanan S, Gopalakrishnan M, Giridhar A, et al. Varicella zoster-related occlusive retinal vasculopathy—a rare presentation. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24(2)227-230.

- ↑ Figueras-Roca M, Rey A, Mesquida M, et al. [Retinal vasculopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case of lupus vasculitis and a case of non-vasculitis venous occlusion]. [Article in Spanish] Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2014;89(2):66-69.

- ↑ Fuest M, Rößler G, Walter P, et al. [Retinal vasculitis as manifestation of multiple sclerosis]. [Article in German] Ophthalmologe. 2014;111(9):871-875.

- ↑ Empeslidis T, Konidaris V, Brent A, et al. Kyrieleis plaques in herpes zoster virus-associated acute retinal necrosis: a case report. Eye (London). 2013;27(9):1110-1112.

- ↑ Biswas J, Sharma T, Gopal L, et al. Eales disease—an update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(3):197-214.

- ↑ Graham EM, Francis DA, Sanders MD. Ocular inflammatory changes in established multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52(12):1360-1363.

- ↑ Caplan L, Corbett J, Goodwin J, et al. Neuro-ophthalmologic signs in the angiitic form of neurosarcoidosis. Neurology. 1983;33(9):1130-1135.

- ↑ Tugal-Tutkun I, Gupta V, Cunningham ET. Differential diagnosis of Behçet uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(5):337-350.

- ↑ Schneider EW, Elner SG, van Kuijk FJ, et al. Chronic retinal necrosis: cytomegalovirus necrotizing retinitis associated with panretinal vasculopathy in non-HIV patients. Retina. 2013;33(9):1791-1799.

- ↑ Ho TY, Chung YM, Lee AF, et al. Severe vaso-occlusive retinopathy as the primary manifestation in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71(7):377-380.

- ↑ Mihara M, Hayasaka S, Watanabe K, et al. Ocular manifestations in patients with microscopic polyangiitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15(1):138-142.

- ↑ Kubal AA, Perez VL. Ocular manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36(3):573-586.

- ↑ Butler NJ, Furtado JM, Winthrop KL, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis II: clinical features, pathology and management. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(1):95-108.

- ↑ Kirkwood BJ. Acute retinal necrosis. Insight. 2014;39(1):14-16.

- ↑ Roy R, Pal BP, Mathur G, et al. Acute retinal necrosis: clinical features, management and outcomes—a 10 year consecutive case series. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22(3):170-174.

- ↑ Or C, Press N, Forooghian F. Acute retinal necrosis secondary to cytomegalovirus following successful treatment of cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis in an immunocompetent adult. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48(2):e18-e20.

- ↑ Levy-Clarke GA, Buggage RR, Shen D, et al. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1 associated t-cell leukemia/lymphoma masquerading as necrotizing retinal vasculitis. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(9):1717-1722.

- ↑ Chazalon E, Conrath J, Ridings B, et al. [Kyrieleis arteritis: report of two cases and literature review]. [Article in French] J Fr Ophtalmol. 2013;36(3):191-196.

- ↑ He L, Moshfeghi DM, Wong IG. Perivascular exudates in frosted branch angiitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45(5):447-450.

- ↑ Kleiner RC. Frosted branch angiitis: clinical syndrome or clinical sign? Retina. 1997;17(5):370-371.

- ↑ Quillen DA, Stathopoulos NA, Blankenship GW, et al. Lupus associated frosted branch periphlebitis and exudative maculopathy. Retina. 1997;17(5):449-451.

- ↑ Sykes SO, Horton JC. Steroid-responsive retinal vasculitis with a frosted branch appearance in Crohns disease. Retina. 1997;17(5):451-454.

- ↑ Oh J, Huh K, Kim SW. Recurrent secondary frosted branch angiitis after toxoplasmosis vasculitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83(1):115-117.

- ↑ Leeamornsiri S, Choopong P, Tesavibul N. Frosted branch angiitis as a result of immune recovery uveitis in a patient with cytomegalovirus retinitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):52.

- ↑ Sanghvi C, Bell C, Woodhead M, et al. Presumed tuberculous uveitis: diagnosis, management, and outcome. Eye (London). 2011;25(4):475-480.

- ↑ Damato E, Chilov M, Lee R, et al. Plasma exchange and rituximab in the management of acute occlusive retinal vasculopathy secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19(5):379-381.

- ↑ Kahloun R, Mbarek S, Khairallah-Ksiaa I, et al. Branch retinal artery occlusion associated with posterior uveitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):16.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Stanford MR, Verity DH. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to patients with retinal vasculitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2000;40(2):69-83.

- ↑ Leder HA, Campbell JP, Sepah YJ, et al. Ultra-wide-field retinal imaging in the management of non-infectious retinal vasculitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):30.

- ↑ Yahia SB, Kahloun R, Jelliti B, et al. Branch retinal artery occlusion associated with Behçet disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19(4):293-295.

- ↑ Tugal-Tutkun I, Herbort CP, Khairallah M. Scoring of dual fluorescein and ICG inflammatory angiographic signs for the grading of posterior segment inflammation (dual fluorescein and ICG angiographic scoring system for uveitis). Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30(5):539-552.

- ↑ Majumder PD, Sudharshan S, Biswas J. Laboratory support in the diagnosis of uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(6):269-276.

- ↑ Campbell JP, Leder HA, Sepah YJ, et al. Wide-field retinal imaging in the management of noninfectious posterior uveitis. Am J Ophthalmology. 2012;154(5):908-911.e902.

- ↑ Wimmersberger Y, Gervaix A, Baglivo E. VZV retinal vasculitis without systemic infection: diagnosis and monitoring with quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30(1):73-75.

- ↑ Cottet L, Kaiser L, Hirsch HH, et al. HSV2 acute retinal necrosis: diagnosis and monitoring with quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29(3):199-201.

- ↑ Singh R, Toor P, Parchand S, et al. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in so-called Eales' disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012;20(3):153-157.

- ↑ Barry RJ, Nguyen QD, Lee RW, et al. Pharmacotherapy for uveitis: current management and emerging therapy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1891-1911.

- ↑ Saurabh K, Das RR, Biswas J, et al. Profile of retinal vasculitis in a tertiary eye care center in Eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(4):297-301.

- ↑ Benítez Del Castillo Sánchez JM, García Sánchez J. [Intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide in non infectious uveitis]. [Article in Spanish] Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2001;76(11):661-664.

- ↑ Roesel M, Gutfleisch M, Heinz C, et al. [Effect of intravitreal and orbital floor triamcinolone acetonide injection on intraocular inflammation in patients with active non-infectious uveitis]. [Article in German] Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2009;226(2):110-114.

- ↑ Kok H, Lau C, Maycock N, et al. Outcome of intravitreal triamcinolone in uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(11):1916.e1911-1917.

- ↑ Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmology. 2000;130(4):492-513.

- ↑ Comarmond C, Wechsler B, Cacoub P, et al. Approaches to immunosuppression in Behçet's disease. Immunotherapy. 2013;5(7):743-754.

- ↑ Whitcup SM, Salvo EC Jr, Nussenblatt RB. Combined cyclosporine and corticosteroid therapy for sight-threatening uveitis in Behçet's disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118(1):39-45.

- ↑ Ozdal PC, Ortaç S, Taskintuna I, et al. Long-term therapy with low dose cyclosporin A in ocular Behçet's disease. Doc Ophthalmol. 2002;105(3):301-312.

- ↑ Greenwood AJ, Stanford MR, Graham EM. The role of azathioprine in the management of retinal vasculitis. Eye (London). 1998;12(pt 5):783-788.

- ↑ Palmares J, Castro-Correia J, Coutinho MF, Araujo D, Delgado L. Immunosuppression in Behçet's disease: clinical management and long-term visual outcome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 1995;3(2):99-106.

- ↑ Davatchi F, Sadeghi Abdollahi B, Shams H, et al. Combination of pulse cyclophosphamide and azathioprine in ocular manifestations of Behcet's disease: longitudinal study of up to 10 years. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17(4):444-452.

- ↑ Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Update on the use of systemic biologic agents in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis. Biologics. 2014;8:67-81.

- ↑ Okinami S, Sunakawa M, Arai I, et al. Treatment of pars planitis with cryotherapy. Ophthalmologica. 1991;202(4):180-186.

- ↑ Davatchi F, Nikbin B, Shams H, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy unable to rescue the vision from advanced Behcet's disease retinal vasculitis: report of three patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16(2):139-147.