Orbital Granular Cell Tumor

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Article summary goes here.

Disease Entity

Disease

Orbital granular cell tumors (GCTs) are rare, typically benign soft tissue neoplasms of Schwann cell origin.[1] First described by Abrikossoff in 1926, these tumors are composed of polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, reflecting lysosome-rich intracytoplasmic inclusions.[2][3][4] The majority of GCTs occur in the head and neck region, most commonly in the tongue.[2] Orbital involvement is uncommon, accounting for roughly 3% of all reported cases.[5][6][7] Within the orbit, GCTs frequently involve or originate in the extraocular muscles, with a predilection for the inferior rectus (around 39- 42% of cases).[5][8] Clinically, orbital GCTs often present with slowly progressive proptosis and restricted ocular motility. Although most orbital GCTs exhibit benign behavior, malignant transformation has been reported in fewer than 7% of cases.[8][9] Malignant variants are associated with an increased risk of local recurrence and distant metastasis.[9][10][11]

Etiology

GCTs are believed to originate from Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system. Initially termed “granular cell myoblastoma” due to their presumed muscle origin, they are now classified as peripheral nerve sheath tumors with neuroectodermal differentiation.[3][12] The exact etiologic trigger for orbital GCTs is unknown. These tumors are thought to arise sporadically within peripheral nerves of the orbit or along the orbital branches supplying the extraocular muscle. At the cellular level, pathogenesis involves the abnormal accumulation of lysosomes within tumor cells, believed to be driven by dysfunction of the vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) pathway although the specific pathway remains under investigation.

Recent genomic studies have identified recurrent, somatic loss-of-function mutations in ATP6AP1 and ATP6AP2, which encode regulators of endosomal pH within the V-ATPase proton pump complex.[13] These mutations are found in approximately 70% of sporadic GCTs, and appear to be pathognomonic. In vitro silencing of ATP6AP1/2 in Schwann cells induces lysosome accumulation and transformation to a tumorigenic phenotype, establishing a direct molecular link between disrupted endosomal acidification and granular cell morphology.[13]

Risk Factors

Orbital GCTs most commonly occur in adults between the ages of 30 and 60 years. Pediatric cases are exceptionally rare but have been reported.[14] A slight female predominance has been observed.[11] Some studies have noted an increased incidence among African American patients; however, this observation is based on limited data and may not be specific to orbital involvement.[15][16] To date, there are no known environmental, behavioral, or genetic risk factors that have been conclusively linked to the development of orbital GCTs.

General Pathology

GCTs are histologically distinctive lesions composed of sheets, nests, or cords of large polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm.[6][17] The granules represent intracytoplasmic lysosomes and are a defining feature of the tumor.[18] Cell borders are typically indistinct, and the cytoplasm is densely packed with coarse, PAS-positive, diastase-resistant granules, reflecting complex carbohydrate and protein content resistant to glycogen digestion.[6] This staining pattern is a diagnostic hallmark of GCT and helps distinguish it from morphologic mimics, such as alveolar soft part sarcoma, which typically shows only focal crystalline inclusions on PAS stain.[19] Tumor cell nuclei are usually small, centrally located, and hyperchromatic, and mitotic activity is absent or minimal. The tumor often exhibits a collagenous stroma, which may compartmentalize clusters of granular cells.[12] Ultrastructural studies have confirmed that the cytoplasmic granules are membrane-bound, electron-dense lysosomes containing residual cellular debris. Early electron microscopy and immunophenotypic analyses revealed features characteristic of Schwann cells, including occasional myelin whorls (mesaxons).[3][20] Malignant GCTs cytologic features include increased cellularity, marked nuclear pleomorphism, focal spindle cell morphology, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli, necrosis, and elevated mitotic activity.[11][21] If several of these features are present, a diagnosis of malignant GCT is considered.

Immunohistochemistry plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis of GCT. Tumor cells are typically positive for S-100 protein and SOX10.[20] Most cells also express neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and vimentin, reflecting neuroectodermal and mesenchymal differentiation. A notable feature is CD68 positivity, which, rather than indicating a histiocytic origin, highlights the lysosome-rich cytoplasm. Other supportive markers, including calretinin, inhibin-α, and myelin basic protein, may also be detected. Tumors are negative for cytokeratins and muscle markers, such as desmin and smooth muscle actin (SMA), which helps exclude epithelial and myogenic neoplasms.[11]

Pathophysiology

In the orbit, GCTs commonly arise along peripheral nerves within the orbital fat or within the motor branches innervating the extraocular muscles. Consequently, these tumors frequently occur within or adjacent to extraocular muscles.[5] In several published series, the inferior rectus muscle was the most commonly involved site, accounting for approximately 42% of cases.[8][11] The medial and superior rectus muscle are also highlighted.[8] Less commonly, orbital GCTs may encase the optic nerve or ciliary nerves in the posterior orbit.[8][11]

GCTs lack a true capsule and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern. Histologically, tumor margins often show interdigitation of tumor cells with normal muscle or nerve fibers. This corresponds with intraoperative findings, where tumors are often adherent to surrounding structures and not easily dissected from adjacent tissues.[8]

The infiltrative nature underlies many of the clinical manifestations. Involvement of an extraocular muscle can lead to restricted motility and diplopia, which may persist after resection due to direct muscle damage or postoperative scarring. Lesions involving the optic nerve or located in the orbital apex may cause compressive optic neuropathy, resulting in decreased visual acuity or visual field deficits. Involvement of the ciliary ganglion may produce pupillary dyskinesia, such as a tonic pupil. While most orbital GCTs are painless, tumors in the orbital apex may present with persistent discomfort. In cases involving the anterior orbit or superficial muscle insertions, patients may present with eyelid swelling or fullness, which reflects tumor extension into the anterior orbit or mechanical displacement of orbital tissues toward the eyelid.

The growth pattern of orbital GCTs is typically indolent. Most tumors enlarge slowly over years, and some may remain stable. Interestingly, there are rare reports of spontaneous regression or long-term arrest of growth following incomplete excision of benign tumors. The mechanism of this phenomenon remains unclear, though immune-mediated processes have been proposed. In one series of partially resected benign orbital GCTs, several showed recurrence, while another demonstrated spontaneous shrinkage over time.[11]

Primary Prevention

There are no established strategies for the primary prevention of orbital granular cell tumors (GCTs). These tumors arise sporadically and are not associated with modifiable environmental, behavioral, or occupational risk factors. Early recognition and biopsy in atypical or refractory orbital disease may reduce morbidity, but no true preventive measures exist.

Diagnosis

History

Orbital GCTs present with a gradually progressive orbital mass that manifests with proptosis, ocular motility restriction, and diplopia in a middle-aged adult.[5][8][22] Pupillary defects may also be present.[8]

Symptoms

Orbital granular cell tumors (GCTs) most often present as slowly progressive, unilateral orbital masses. Proptosis, diplopia, and ocular motility restriction are the most common presenting features.[8][22] When extraocular muscles are involved, patients may report diplopia or globe prominence that is position-dependent due to mechanical tethering.

Pain is uncommon but may occur in tumors involving the orbital apex or posterior orbit.[8] Acute or severe pain is atypical and should prompt consideration of inflammatory or malignant processes. Visual disturbances, including blurred vision or field deficits, may occur if the optic nerve is compressed.[11]

Physical Examination

The exam in orbital GCT typically reflects a localized, unilateral orbital mass. Proptosis is usually axial and subtle, unless the tumor is large enough to cause globe displacement, which may occur opposite the lesion. Anterior tumors may manifest as eyelid swelling, a palpable nodule, or ptosis.[17] Large lesions may result in venous stasis, occasionally seen as conjunctival injection or chemosis.

Extraocular motility is frequently restricted in the field of the involved muscle, with positive forced duction testing suggesting mechanical limitation. Diplopia is often binocular and position dependent. Pupillary function is generally normal unless optic nerve compression produces a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Rarely, a tonic pupil may be observed. Visual acuity and color vision are typically preserved in the early stages of the disease but may decline with optic nerve involvement. Perimetry may reveal arcuate or central scotomas. Fundus examination is usually normal but may show optic disc pallor or swelling in advanced cases. Choroidal folds or scleral indentation may occur with posteriorly located masses. Overall, examination findings mirror those of other orbital tumors but are usually confined to a unilateral, localized process without systemic features.

Diagnostic Procedures

Radiology

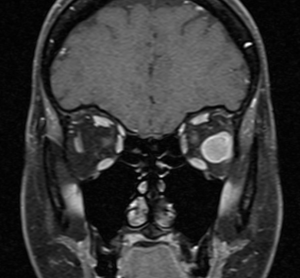

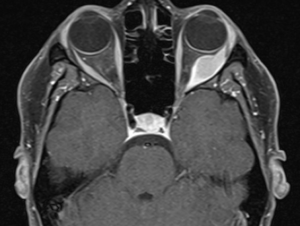

High-resolution orbital imaging is essential for the evaluation of suspected orbital GCTs. Both Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) offer complementary information, with MRI generally favored for lesion characterization. The majority of infraorbital GCTs appear as well circumscribed, round lesions.[23] On CT, they appear as well-defined, homogeneous soft tissue masses that are isodense or mildly hyperdense to muscle.[8] Adjacent bony changes are uncommon, a finding better appreciated on CT.[23] On contrast-enhanced CT, GCTs typically show moderate, homogeneous enhancement.[23] On MRI, Orbital GCTs are generally isointense to gray matter on T1-weighted imaging and hypointense to isointense on T2-weighted sequences, a pattern that differs from most benign orbital tumors, which are typically T2-hyperintense.[8][23] MRI with gadolinium demosntrates slight to strong enhancement with avid peripheral enhancement (see image 1 and 2). [4][8] Diffusion weighted imaging generally does not show diffusion restriction.[23] ADC measurements have been investigated for use in differentiating benign from malignant lesions, however there is not a specific value which supports a diagnosis of GCT. [23]

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Histologic examination of GCTs reveals sheets or nests of polygonal cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and small, uniform nuclei. The cytoplasmic granules are PAS-positive and diastase-resistant. Evaluation of mitotic activity, nuclear atypia, necrosis, and Ki-67 proliferation index helps assess whether the tumor exhibits benign or malignant features. Due to overlapping morphologic features, histopathologic mimics such as alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) and melanoma should be considered. ASPS may show PAS-positive granular cytoplasm, while melanoma may contain pigmented granular cells. Calretinin and inhibin-α are often positive and useful for distinguishing GCT from ASPS, which lacks expression of these markers. TFE3 may be weakly positive in GCT, but strong nuclear TFE3 expression favors ASPS. Importantly, GCTs are negative for cytokeratins, desmin, SMA, myogenin, HMB-45, and Melan-A, which helps exclude epithelial, myogenic, and melanocytic tumors. The typical IHC profile of GCT includes S-100(+), SOX10(+), CD68(+), calretinin(+), inhibin-α(+), cytokeratin(-), desmin(-), and myogenin(-).[19][24][25]

Differential Diagnosis

Orbital granular cell tumors must be differentiated from a spectrum of other orbital lesions, including both neoplasms and inflammatory conditions. Key differentials include schwannoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, melanoma, ASPS, and orbital inflammatory diseases such as thyroid eye disease (TED) or idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI).[8]

Schwannomas are S–100–positive like GCTs but are typically T2-bright on MRI, lack granular cytoplasm, and are CD68-negative. Rhabdomyosarcomas occur in children, are desmin-positive, T2-bright, rapidly progressive, and clinically aggressive. Melanomas may involve the orbit in patients with known uveal or conjunctival primaries and express HMB-45 and Melan-A, which are negative in GCT. ASPS closely mimics GCT due to PAS positivity and muscle involvement but is S-100/SOX10-negative and shows strong nuclear TFE3 expression due to an ASPL-TFE3 gene fusion.[19] Inflammatory conditions such as TED and IOI typically show diffuse muscle or fat involvement without a discrete mass.

Management

General Treatment

Management of orbital granular cell tumor is individualized based on the tumor’s size, location, and behavior. In general, complete surgical excision is the preferred primary treatment for orbital GCT. Adjuvant therapies have been considered in select cases but their use is controversial and data is limited.

Medical Therapy

In the context of malignant GCT or metastatic disease, oncologists have attempted various systemic treatments by analogy with other soft tissue sarcomas, such as conventional chemotherapy, targeted anti-angiogenic therapy , and immunotherapy.[9]

At present, no identified medical therapies have demonstrated proven efficacy.

Surgery

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for accessible orbital GCTs, and the approach will depend on the tumor location. The goal is to achieve wide local excision with clear margins because complete removal is usually curative for benign tumors. However, achieving clean margins can be challenging due to the tumor’s tendency to infiltrate muscle or nerve fibers.

Radiation Therapy

While the literature is sparse, reports of orbital GCT treated with traditional radiation supports that is an ineffective treatment option, with tumors failing to respond and ultimately requiring exenteration.[26] This is in contrast to literature on GCT elsewhere in the body which supports radiation use for cases where complete surgical resection is not possible or for tumors with recurrent disease.[27][28]

Proton beam radiation therapy (PBRT) presents a potential avenue to explore for orbital GCTs in whom surgical resection poses high morbidity.[8] The proton beam offers targeted dose deposition, which is valuable in the orbit to spare surrounding sensitive tissues from excessive radiation. In a recent case, a patient with an orbital GCT abutting the optic nerve had incomplete resection; proton beam therapy was employed, resulting in significant tumor regression and symptomatic relief.[8]

Observation

Observation may be warranted for GCTs without evidence of malignancy on biopsy, no evidence of compressive optic neuropathy or visual compromise, and for which surgical resection may result in high ocular morbidity. These patients should undergo regular imaging surveillance to monitor for tumor change and serial examinations to monitor for change in ophthalmic status.

Follow-up

Patients should be followed at routine intervals post operatively to ensure they recover appropriately. The frequency of follow up thereafter depends on presence of residual or metastatic disease, and may require coordination with a medical or radiation oncologist.

In the event the tumor is observed, close follow up is indicated with routine surveillance imaging to monitor for change in tumor or ophthalmic exam which may prompt surgical intervention.

Complications

Complications for surgical resection include infection, bleeding, bruising, loss of vision, diplopia, need for repeat surgery, and need for additional adjuvant treatment.

Importantly, literature supports that patients with GCT who are diplopic prior to surgery are likely to remain diplopic post operatively.[5]

References

- ↑ JC G, RA K, JF K. Granular cell myoblastoma - PubMed. Cancer. 1970 Mar;25(3)doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197003)25:3<542::aid-cncr2820250308>3.0.co;2-6

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Neelon D, Lannan F, Childs J. Granular Cell Tumor. StatPearls. 2025

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 NG O, B M. Granular cell tumor: a review of the pathology and histogenesis - PubMed. Ultrastructural pathology. 1999 Jul-Aug;23(4)doi:10.1080/019131299281545

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Vega Gdl, Villegas VM, Velazquez J, et al. Intraorbital Granular Cell Tumor Ophthalmologic and Radiologic Findings. The Neuroradiology Journal. 2015 Apr;28(2)doi:10.1177/1971400915576657

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 SF R, F C, AA C. Oculomotor disturbances due to granular cell tumor - PubMed. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012 Jan-Feb;28(1)doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182141c54

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 BF F, R BN, AN O, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of orbital granular cell tumor: case report - PubMed. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia. 2012 Mar-Apr;75(2)doi:10.1590/s0004-27492012000200014

- ↑ T Y, A V, H K, Y T. Granular Cell Tumor in the Medial Rectus Muscle: A Case Report - PubMed. Case reports in ophthalmology. 01/31/2022;13(1)doi:10.1159/000521685

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 PC B, P Z, SM M, et al. Granular Cell Tumor of the Orbit: Review of the Literature and a Proposed Treatment Modality - PubMed. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2022 Mar-Apr;38(2)doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000002038

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 S M, M H, M S, et al. Pazopanib monotherapy in a patient with a malignant granular cell tumor originating from the right orbit: A case report - PubMed. Oncology letters. 2015 Aug;10(2)doi:10.3892/ol.2015.3263

- ↑ Salour H, Tavakoli M, Karimi S, et al. Granular cell tumor of the orbit. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. Oct 2013;8(4):376-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Li X-F, Qian J, Yuan Y-F, et al. Orbital granular cell tumours: clinical and pathologic characteristics of six cases and literature review. Eye 2016 30:4. 2016-01-08;30(4)doi:10.1038/eye.2015.268

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Wang P, Han Z, Peng L, et al. Frontiers | Orbital granular cell tumor involving the superior rectus muscle: a case report. Frontiers in Oncology. 2024/11/07;14doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1456960

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Pareja F, Brandes AH, Basili T, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in ATP6AP1 and ATP6AP2 in granular cell tumors. Nature Communications 2018 9:1. 2018-08-30;9(1)doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05886-y

- ↑ J Y, X R, Y C. Granular cell tumor presenting as an intraocular mass: a case report - PubMed. BMC ophthalmology. 04/25/2019;19(1)doi:10.1186/s12886-019-1102-5

- ↑ NG O. Granular cell tumor: a review and update - PubMed. Advances in anatomic pathology. 1999 Jul;6(4)doi:10.1097/00125480-199907000-00002

- ↑ EE L, GF W, MD C, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients - PubMed. Journal of surgical oncology. 1980;13(4)doi:10.1002/jso.2930130405

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Golio DI, Prabhu S, Hauck EF, Esmaeli B. Surgical Resection of Locally Advanced Granular Cell Tumor of the Orbit. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2006;17(3):594-598.

- ↑ SL vH, J Ø, S D, et al. Granular cell tumour of the lacrimal gland - PubMed. Acta ophthalmologica. 2009 Nov;87(8)doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01655.x

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 BK C, CM M, RS G, et al. Alveolar soft part sarcoma and granular cell tumor: an immunohistochemical comparison study - PubMed. Human pathology. 2014 May;45(5)doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2013.12.021

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 ER F, H W. Granular cell myoblastoma--a misnomer. Electron microscopic and histochemical evidence concerning its Schwann cell derivation and nature (granular cell schwannoma) - PubMed. Cancer. 1962 Sep-Oct;15(5)doi:10.1002/1097-0142(196209/10)15:5<936::aid-cncr2820150509>3.0.co;2-f

- ↑ JC F-S, JM M-K, R F, LG K. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation - PubMed. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1998 Jul;22(7)doi:10.1097/00000478-199807000-00001

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Emesz M, Arlt EM, Krall EM, et al. [Granular cell tumors of the orbit: diagnostics and therapeutic aspects exemplified by a case report]. Granularzelltumor der Orbita: Diagnostische und thera-peutische Aspekte anhand eines Fallberichtes. Ophthalmologe.2014;111:866–870.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Yuan, WH., Lin, TC., Lirng, JF. et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of intraorbital granular cell tumor (Abrikossoff’s tumor): a case report. J Med Case Reports 10, 119 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-016-0896-5

- ↑ SW F, M L. Expression of calretinin and the alpha-subunit of inhibin in granular cell tumors - PubMed. American journal of clinical pathology. 2003 Feb;119(2)doi:10.1309/GRH4-JWX6-J9J7-QQTA

- ↑ BH L, PJ B, JE L, SB K. Granular cell tumor: immunohistochemical assessment of inhibin-alpha, protein gene product 9.5, S100 protein, CD68, and Ki-67 proliferative index with clinical correlation - PubMed. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2004 Jul;128(7)doi:10.5858/2004-128-771-GCTIAO

- ↑ Salour H, Tavakoli M, Karimi S, Rezaei Kanavi M, Faghihi M. Granular cell tumor of the orbit. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013 Oct;8(4):376-9. PMID: 24653826; PMCID: PMC3957045.

- ↑ Marchand Crety, C., Garbar, C., Madelis, G. et al. Adjuvant radiation therapy for malignant Abrikossoff’s tumor: a case report about a femoral triangle localisation. Radiat Oncol 13, 115 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-018-1064-4

- ↑ Rosenthal SA, Livolsi VA, Turrisi AT. Adjuvant radiotherapy for recurrent granular cell tumor. Cancer 15 févr. 1990;65(4):897–900.