Ocular Ischemic Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS) is a rare but vision-threatening condition associated with severe carotid artery occlusive disease (stenosis or occlusion) leading to ocular hypoperfusion. Principal symptoms include visual loss, transient visual loss, and ischemic ocular pain.[1][2][3] Ocular ischemic syndrome commonly occurs in older individuals, with men more affected than women. In addition, OIS has important systemic implications, as disease of the common (CCA) or internal (ICA) carotid arteries may cause ipsilateral ocular signs and symptoms that in turn could herald a cerebral infarction.[4]

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Ocular ischemic syndrome most commonly occurs in the sixth decade of life; it is uncommon before the age of 50 years and has no racial predilection. Men are affected twice as often as women, likely owing to the higher incidence of atherosclerosis and carotid artery disease in male patients.[5][6][7] Bilateral involvement may occur in up to 22% of cases.[8][9][10] The degree of stenosis, presence or absence of collateral vessels, chronicity of carotid artery disease, bilaterality of disease, and associated systemic vascular diseases help contextualize the severity of OIS.[11]

The incidence of OIS has been estimated at 7.5 cases per million persons per year.[12] However, this is probably an underestimation, as OIS may be misdiagnosed as retinal vein occlusion or diabetic retinopathy. Approximately 30% of patients with symptomatic carotid occlusion manifest retinal vascular changes that are usually asymptomatic, and 1.5% of these progress to symptomatic OIS each year.[13] Among patients with ICA occlusion undergoing surgical anastomosis between the superficial temporal artery and the middle cerebral artery, 18% presented with OIS.[6]

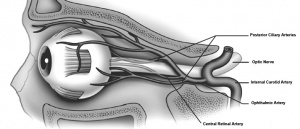

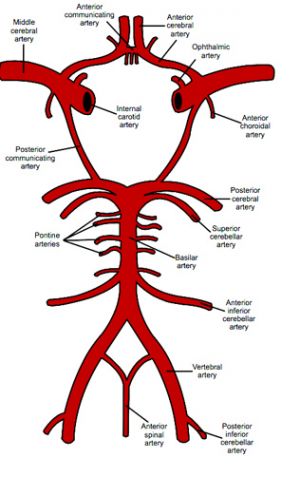

Arterial Blood Supply

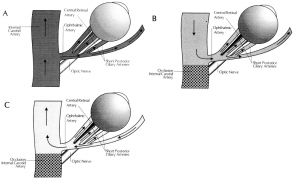

Ocular ischemic syndrome develops especially in patients with poor collateral circulation between the ICA and external carotid artery (ECA) systems or between the right and left ICA (Figure 1). Patients with healthy collateral circulation may not develop OIS, even with total occlusion of the ICA. In contrast, in patients with poor collaterals, an ICA stenosis <50% may be sufficient to develop OIS. Patterns of occlusion vary from <50% stenosis to complete occlusion of at least one CCA or one ICA, often accompanied by occlusion or stenosis of the opposite carotid arterial system.[14]

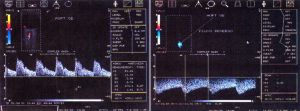

Patients who develop OIS show decreased blood flow in the retrobulbar vessels and reversal of blood flow in the ophthalmic artery (OA).[15] The OA may behave as a steal artery shunting blood flow away.[16] Figure 2 and Figure 3 demonstrate blood flow through these blood vessels in a healthy individual and one with internal carotid artery occlusion and collateral circulation via the ophthalmic artery (reversed flow).[16]

Diagnosis and Ancillary Tests

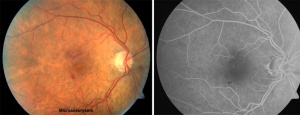

Fluorescein Angiogram

Fluorescein angiography can help to establish a diagnosis of OIS.[5][17] Particularly characteristic findings are delayed choroidal filling time (most specific angiographic sign) and prolonged arteriovenous (AV) transit time (most sensitive angiographic sign), along with retinal vascular staining in 85% of affected individuals .[5]

The choroid normally fills completely within 5 seconds after the first appearance of the dye in the choroidal arteries. Patchy or delayed choroidal filling is seen 60% of eyes with OIS, with prolonged retinal arteriovenous time present in up to 95% of eyes and a severe filling delay of >1 minute in some cases (Figure 4).[5] Arterial and early and late venous circulation times are also prolonged. However, delayed retinal circulation time is also observed in eyes with central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) or central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). Staining of the retinal vessels is commonly seen and has been suggested to be due to endothelial cell damage, with rupture of the inner blood–retina barrier due to chronic ischemia. This staining can imitate the angiographic appearance of frosted branch angiitis seen in inflammatory conditions.

About 15% of eyes with OIS show macular edema at the late phase of the fluorescein angiography.[18] Leakage from microaneurysms or from telangiectasia may occur, resulting in increased retinal thickness. Intraretinal fluid accumulation is usually mild to moderate, does not have a cystoid pattern, and tends to be associated with hyperfluorescence of the optic disk (attributed to leakage from blood vessels). Some eyes also show retinal capillary nonperfusion. Arterial staining is more prominent with OIS. Optic disc hyperfluorescence, peripheral microaneurysms, and peripheral perivascular staining are other angiographic features.

Indocyanine Green Angiography

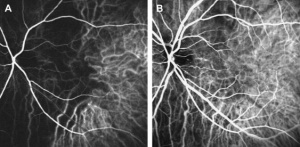

Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography allows for better evaluation of the choroidal vascular abnormalities.[19] Patients with OIS demonstrate prolonged arm-to-choroid circulation time (time from dye injection to the first appearance of the dye in the choroidal arteries; ~10 seconds in healthy individuals) and intrachoroidal circulation time (time from the first appearance of the dye in the choroidal arteries to complete dye filling in the choroidal veins; ~5–6 seconds in healthy individuals). Choroidal hypoperfusion results in occlusions of the choriocapillaris, with areas of vascular filling defects in the posterior pole or the mid-periphery. Delayed filling or occlusion of the choriocapillaris in the peripheral watershed zones can also be observed (Figure 5).[20]

Electroretinography

On an electroretinograph (ERG), the b-wave corresponds to activity of Müller and/or bipolar cells and reflects the functional status of the inner retinal layer, whereas the a-wave corresponds to activity of photoreceptors. In CRAO, where there is ischemia of the inner retina, the amplitude of the b-wave is decreased. In contrast, in eyes with OIS where both the retinal and choroidal circulation are compromised, there is ischemia of the inner and outer retina, resulting in decreased amplitudes of both the a-wave and b-wave.[5] Reduction in the amplitude of the oscillatory potential of the b-wave has been demonstrated in eyes with carotid artery stenosis even if the fluorescein angiography is normal. Carotid artery surgery increases ocular blood flow, leading to improved retinal function, and has been suggested to increase a- and b-wave amplitudes (Figure 6). [21]

Visual-evoked Potentials

Visual-evoked potentials (VEPs) after exposure to intense light stimulation (photostress) show an increase in latency and a decrease in amplitude with OIS. The time it takes the VEP to recover to the baseline status (i.e., recovery time after photostress) ranges between 68 and 78 seconds in normal individuals; recovery is prolonged in patients with severe carotid artery stenosis and improves following endarterectomy surgery. The VEPs may elicit visual dysfunction prior to the appearance of other ophthalmological signs.

Ophthalmodynamometry

Ophthalmodynamometry is used to estimate the pressure in the ophthalmic artery (OA) at the origin of the central retinal artery (CRA). Measurements are performed by gradually applying pressure to the globe to increase IOP and observing the arteries on the optic disc until they begin to pulsate.[22][23] The pressure required to produce artery pulsations on the optic disc reflects the OA diastolic pressure, whereas the force required to cause cessation of arterial pulsations reflects the OA systolic pressure. In OIS, the CRA perfusion pressure is low and, for this reason, the pressure necessary for the pulsations to appear is reduced. Diastolic readings, which are decreased in OIS, may improve or return to normal after carotid artery surgery and are considered to be more reliable than systolic readings.

Imaging for Evaluation of Carotid Occlusive Disease

Carotid Duplex Ultrasound

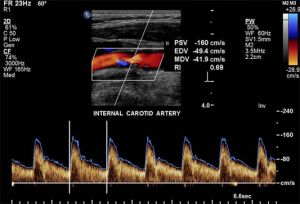

Carotid duplex ultrasonography is the most commonly used non-invasive test for carotid occlusive disease. It combines B-mode ultrasound and Doppler ultrasound, providing both anatomical imaging of the vessel and information on flow velocity. The parameters used to classify the severity of stenosis include peak systolic velocity (PSV), end-diastolic velocity, and the ICA/CCA PSV ratio. Compared to conventional intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography (DSA), duplex ultrasound has good ability to detect high-grade symptomatic carotid artery stenosis (89% sensitivity, 84% specificity) and is excellent for detecting occlusion (96% sensitivity, 100% specificity) (Figure 7).

Peak Systolic Velocity (cm/sec) and ICA Stenosis (% diameter)

- PSV 125 – 225 cm/sec → 50–70% ICA stenosis

- PSV 225–350 cm/sec → 70–90% ICA stenosis

- PSV >350 cm/sec → 90% ICA stenosis

Color Doppler Imaging

Color doppler imaging of retrobulbar vessels is a useful adjunct to conventional duplex ultrasound for carotid artery examination. Distal to a hemodynamic significant stenosis, blood pressure is decreased and the Doppler effect is dampened, causing diminished blood flow velocity. Therefore, studying the flow profile in the OA, the CRA, and the short posterior ciliary arteries (SPCA) may provide hemodynamic information about the carotid and retrobulbar circulations of the orbital arteries (e.g., velocities and pulsatility indices, an indicator of vascular resistance). These parameters are significantly reduced in patients with significant carotid artery stenoses as compared to a normal, age-matched population with no carotid disease. Doppler imaging of retrobulbar vessels also allows studying the flow direction in the OA; reversed OA flow pattern is a highly specific indicator of ipsilateral high-grade ICA stenosis or occlusion (Figure 8). [16]

Magnetic Resonance Angiography and Computed Tomographic Angiography

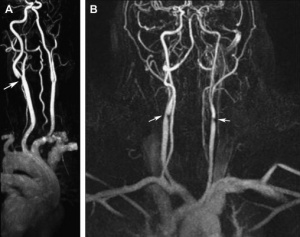

New non-invasive or minimally invasive methods such as magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) (Figure 9) and computed tomographic angiography (CTA) (Figure 10) are increasingly used as second-line investigative tools after duplex ultrasound for carotid stenosis and have gradually replaced DSA .[20]

A review of carotid MRA performance data found that for the diagnosis of 70–99% carotid stenosis, MRA superior pooled sensitivity (95%) and specificity (90%) to conventional DSA.[24] For the detection of complete occlusions, MRA showed similar performance to duplex ultrasound, with a sensitivity of 98% and a specificity of 100%. However, MRA has some limitations, including claustrophobia, pacemakers, obesity, and metallic stents or implantable defibrillators.

Potential advantages of MRA and CTA over conventional angiography include their abilities to allow better carotid plaque characterization and identification and to simultaneously evaluate for cerebrovascular accident.[25] The combined use of MRA, CTA, and doppler ultrasound improves diagnostic accuracy for high-grade symptomatic carotid stenoses and minimizes the need for invasive carotid arteriography. Disadvantages of CTA include the necessity of administering a nephrotoxic iodinated contrast agent and ionizing radiation and the potential for artifacts related to heavily or circumferentially calcified arterial walls.

Carotid Arteriography

Conventional intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography has been considered the gold standard for imaging the cerebrovascular system. However, the risks of disabling cerebral infarction, systemic complications, and high cost make it less than ideal for screening and follow-up. In patients with arteriosclerosis, reports have found arteriography to be associated with a 4% risk of transient ischemic attack or minor cerebral infarction, a 1% risk of major cerebral infarction, and a <1% risk of mortality.[26] In patients with OIS, who have poor collateral circulation and severe carotid artery disease, arteriography-related risks may be even higher (Figure 11).

Overall, carotid duplex ultrasound should be chosen as the first-line investigation for patients suspected of having carotid stenosis. If surgically significant stenosis is identified or in equivocal cases, further imaging with either MRA or CTA should be performed. Digital subtraction angiography should be performed only if results are contradictory or inconclusive.[20]

Symptoms

Overview

As OIS is an ocular manifestation of systemic disease, patients with OIS may initially present with constitutional rather than ocular symptoms. In a review of 42 patients with OIS, only 6 reported developing ocular symptoms as their initial complaint. Patients may also overlook their ocular symptoms due to the prominence of other complaints; the same study found that 37 of 42 patients with OIS initially visited non-ophthalmology clinics for evaluation, yet all 37 reported experiencing ocular symptoms to some degree upon further questioning. Symptoms associated with OIS warrant a thorough history combined with careful evaluation to avoid misdiagnosis.[27]

Patients with OIS may be asymptomatic or report multiple nonspecific ocular symptoms, making correct diagnosis a challenge, especially in patients with comorbid ocular disease. In a study by Luo et al., 35 of 42 patients with OIS presented with more than two ocular symptoms, including visual loss, ocular/periorbital pain, amaurosis fugax, photophobia, floaters, metamorphopsia, phosphenes, and diplopia.[27]

Visual Loss

Decreased visual acuity (VA) in OIS may be severe, with acute or subacute presentation. Studies found that 35–43% of eyes with OIS had a VA of 20/20 to 20/40 or 20/50 at initial presentation and 35–37% had vision of counting fingers or worse.[5][10] Mizener et al. reported initial VA of 20/40 or better in only 15% of cases, whereas 65% had VA of less than or equal to 20/400.[11]

With OIS, visual fields on presentation can vary greatly from normal to having a central scotoma, nasal defects, centrocecal defects, or the presence only of a central or temporal island.[11]

A history of transient visual loss is present in approximately 10–15% of patients with OIS. This is most frequently caused by transient embolization of the CRA or its branches, but vasospasm may also play a role. In these cases, a dark or black shade spreads across the visual field and lasts for a few seconds to minutes. Less commonly, severe carotid artery disease causes transient visual loss as a result of choroidal hypoperfusion. Conditions that either increase retinal metabolic demands or decrease perfusion pressure can precipitate transient visual loss and reflect the inability of a borderline ocular circulation to maintain stable ocular blood flow. This phenomenon has been reported following exposure to bright light, postural change, or after eating a meal. Visual loss resulting from hypoperfusion of the choroid often lasts several minutes to hours and may be associated with positive visual phenomena.

Pain

Pain may be present in up to 40% of eyes with OIS, and may result from increased IOP, ischemia, or both.[6][11] Ischemic pain (sometimes referred to as "ocular angina") is described as a dull, constant ache in the affected eye, over the orbit, and in the upper face and temple. Beginning gradually over hours to days, ischemic pain may worsen when the patient is upright, whereas lying down relieves or lessens the pain. Ischemic pain can be confused with pain from secondary glaucoma, but pain in eyes with OIS would not be explained by a slight IOP elevation. In older patients, giant cell arteritis should be excluded.

Signs

Signs of ocular ischemic syndrome are summarized in Table 1.[20]

| Anterior Segment | Posterior Segment | Orbital |

|---|---|---|

| Conjunctival and episcleral injection | Narrowed retinal arteries | Orbital pain |

| Corneal edema and Descemet's folds | Dilated retinal veins | Anterior and posterior segment ischemia with intraocular inflammation and hypotony |

| Corneo-scleral melting | Retinal hemorrhages (mid peripheral) | Ophthalmoplegia |

| Corneal hypoesthesia | Microaneusyms (mid peripheral) (Figure 12) | Ptosis |

| Spontaneous hyphema | Macular capillary telangiectasia | |

| Iris atrophy | Retinal arteriovenous communications | |

| Fixed semi-dilated pupil or sluggish reaction to light with relative afferent pupil defect | Cotton-wool spots | |

| Anterior and posterior synechiae | Cherry-red spot | |

| Uveal ectropion | Neovascularization of disc | |

| Rubeosis iridis (Figure 13) | Neovascularization elsewhere | |

| Neovascular glaucoma | Choroidal neovascular membrane | |

| Iridocyclitis (cell, flare, keratic precipitates) | Vitreous hemorrhage | |

| Asymmetric Cataract/arcus/ | Cholesterol Emboli, Spontaneous retinal arterial pulsations, anterior ischemic optic retinopathy, wedge shaped areas of chorio-retinal atrophy | |

| Asymmetric diabetic retinopathy | ||

| Hard exudates are usually not seen in OIS alone |

Systemic Associations

Atherosclerosis of the carotid vascular system is the major cause of OIS and may be its initial manifestation.[5][28][29] Atherosclerotic plaques are usually located at the site of carotid bifurcation or at the proximal segment of the ICA, though an intracranial carotid artery stenosis may also lead to OIS. Generally, eyes with OIS show ≥90% stenosis of the ipsilateral carotid arterial system. Rarely, the site of occlusion is the ophthalmic artery or bilateral ECAs.

Ocular ischemic syndrome has been reported to be the initial manifestation of carotid occlusive disease in approximately 70% of patients. Patients with OIS often have systemic vascular diseases that are related to atherosclerosis (e.g., ischemic heart disease, previous cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, systemic arterial hypertension, diabetes).[30] The prevalence of systemic arterial hypertension and diabetes is significantly higher among patients with OIS compared to controls. In addition, patients with OIS have a significantly higher average stroke rate (4% per year) than controls (0.49% per year). Patients with arteritis may also have OIS, including patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA), aortic arch syndrome, Takayasu arteritis, carotid artery dissection, hyperhomocysteinemia, radiotherapy of the neck with carotid occlusion, thyroid orbitopathy, Moyamoya disease,neurofibromatosis, or scleroderma.

Differential diagnosis

Diabetic retinopathy and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) are the two most likely conditions to be confused with OIS. One differentiating feature is that eyes with OIS tend to have low retinal artery pressure. Table 2 lists other clinical and angiographic signs that help to differentiate these conditions.[20]

| Clinical Sign | Ocular Ischemic Syndrome | Central Retinal Vein Occlusion | Diabetic Retinopathy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal Veins | Dilated but not tortuous | Dilated and tortuous | Dilated and beaded |

| Age | 50's to 80's | Variable | 50's to 80's |

| Hemorrhages (location) | dot and blot (mid-periphery) and in deeper retinal layers | Flame shaped (all quadrants) in nerve fiber layer | Dot and blot (posterior pole and mid-periphery) |

| Microaneurysms (Location) |

Common (mid-periphery) |

Uncommon | Common (Posterior pole) |

| Other Microvascular abnormalities | Macular telangiectasias, retina AV communications, capillary dropout | opto-ciliary shunts, capillary dropouts | intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, capillary dropout |

| Hard exudates | No | Rare | Common |

| Optic Disc | Normal | Edema (common) | Rarely diabetic papillopathy |

| Central retinal artery perfusion pressure | Decreased | Normal | Normal |

| Fluorescein Angiography | |||

| A-V transit time | Prolonged | Prolonged | Usually normal |

| Retinal Vessel Staining | Arteries>Veins | Veins>Arteries | Usually absent |

| Macular edema | Rare | Common | Common |

| Choroidal filling | Delayed, patchy | Normal | Usually normal |

| Microaneurysm | mid peripheral | usually at posterior pole | usually at posterior pole |

| Optic disc hyperfluorescence | may be present | Usually present | absent except papillopathy or new vessels at the disc or optic neuropathy |

The differential diagnosis of OIS should also include the hyperviscosity syndromes. Fundus manifestations caused by serum or blood hyperviscosity include optic disk swelling, retinal capillary microaneurysms, cotton-wool spots, retinal hemorrhages, dilated retinal veins, and retinal venous occlusion. A basic workup should therefore include a complete blood cell count with differential, serum protein electrophoresis, and immunoelectrophoresis.

Management of Ocular Ischemic Syndrome

The management of OIS involves a multidisciplinary approach. The aim is threefold: firstly to treat the ocular complications and prevent further damage, secondly to investigate and treat the associated vascular risk factors, and thirdly to perform vascular surgery whenever indicated.

Ocular treatment

The ocular treatment is directed toward control of anterior segment inflammation, retinal ischemia, increased IOP, and neovascular glaucoma. Topical therapy includes steroids to suppress anterior segment inflammation as well as cycloplegics to stabilize the blood–aqueous barrier and limit iris movement in order to decrease the likelihood of a spontaneous hyphema. Medical treatment of increased IOP consists of ocular hypotensive agents that reduce aqueous outflow (e.g., topical β-adrenergic blockers or α-agonists that also increase uveoscleral flow) along with topical and/or oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Prostaglandins, pilocarpine, and other anticholinergic agents should be avoided whenever possible because they may increase ocular inflammation.

If neovascular glaucoma develops, IOP control is usually refractory to medical therapy, and surgery (e.g., trabeculectomy with antimetabolites or aqueous shunt implants) or diode laser cyclophotocoagulation is often required. In patients who are in pain and who have no useful vision and limited potential for visual recovery, cycloablation is a viable option. If the eye remains painful, retrobulbar injection of alcohol or chlorpromazine may provide relief. If these fail to alleviate pain in a blind eye, enucleation or evisceration should be considered.

Panretinal photocoagulation may be effective in same patients with ocular neovascularization caused by carotid occlusive disease and might prevent development of neovascular glaucoma. In eyes with poor fundus visualization, 360° transconjunctival cryotherapy or transscleral diode laser retinopexy may be considered.[31][32]

Intravitreal anti-VEGF agents, such as bevacizumab and ranibizumab, and triamcinolone have been used in the treatment of iris neovascularization and cystoid macular edema complicating OIS.

Systemic Medical Treatment

Patients with OIS should be referred to a primary care physician as well as a neurologist for full medical and neurological assessment. It is essential to treat associated systemic diseases. In addition, lifestyle modifications such as cessation of smoking and weight reduction need to be recommended.

Surgical Treatment

A multidisciplinary approach is essential when considering surgery in patients with OIS factoring in the patients anatomic considerations and associated co-morbidities.

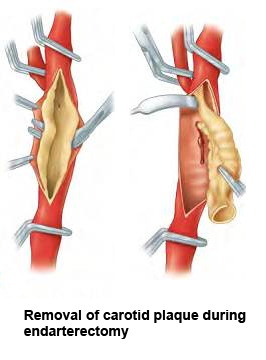

Carotid Artery Endarterectomy

The landmark North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy (NASCET) trial demonstrated the superiority of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and aspirin therapy in preventing stroke (compared with aspirin therapy alone) for both symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis.[33][34] Based on this trial, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association recommend CEA for symptomatic stenosis of 50–99% if the perioperative risk of stroke or death is <6%.[35] In asymptomatic patients, CEA is recommended for a stenosis of 60–99% if the perioperative risk of stroke or death is <3%. (Figure 14)

Carotid endarterectomy has been shown to be effective in reversing or preventing the progression of chronic ocular ischemia or in increasing ocular blood flow. [36][37][38] Peak systolic velocity of flow in the ophthalmic artery rises after surgery, and any reversal of ophthalmic artery flow is corrected.[39][40] Carotid artery surgery can therefore reduce ocular ischemia and improve hypotensive retinopathy as well as reduce the risk of stroke. However, the presence of iris neovascularization implies a greater degree of ocular ischemia and damage, making reversal of ischemia and visual recovery unlikely and limiting any beneficial effect of CEA on visual acuity.

Carotid endarterectomy usually improves ocular hemodynamic parameters, but stabilization or improvement in vision seems to occur only when performed early before development of iris neovascularization or neovascular glaucoma. Carotid endarterectomy is also beneficial in preventing cerebral infarctions.

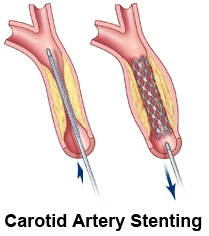

Carotid Artery Stenting

Endovascular carotid artery stenting (CAS) is a treatment alternative for patients who are considered to be at high-risk for complications after CEA, including those with anatomic conditions rendering surgery technically difficult (e.g., previous neck irradiation or radical neck surgery, recurrent stenosis after CEA, contralateral recurrent laryngeal-nerve palsy, tracheostomy, carotid stenosis above the C2 vertebral body).[41] Certain medical conditions that increase the risk of surger are also indications for CAS (e.g., unstable angina, recent myocardial infarction, multivessel coronary disease, congestive heart failure). Carotid artery stenting has been shown to improve the ocular blood flow in patients with acute and chronic forms of OIS. [42] (Figure 15)

Extracranial–Intracranial (EC-IC) Arterial Bypass Surgery

EC-IC bypass surgery involves the surgical anastomosis of the superficial temporal artery (STA) with a branch of the middle cerebral artery (MCA). It is indicated when there is complete occlusion of the ICA or the CCA or when ICA stenosis is inaccessible (at or above the C2 vertebral body) to CEA.[43] The aim of EC-IC bypass is to increase cerebral blood flow and prevent the development of cerebral ischemia.

Prognosis

Although many patients present with relatively good vision, up to 50% of patients who present with OIS may have vision at count fingers (CF) or less within one year. Rubeosis iridis, also known as neovascularization of the iris (NVI), has been shown to be a poor prognostic indicator, with progression to CF or worse in 80% of patients who presented with NVI or who had NVI within 3 months of presentation. Interestingly, the duration of macular ischemia may be a better prognostic indicator than initial visual acuity.[44]

In a review of 25 patients with OIS, 17 patients (68%) subsequently developed neovascular glaucoma (NVG). In this study, development of NVG was significantly associated with IOP at time of diagnosis, length of time between symptom onset and diagnosis, and extent of ipsilateral carotid artery stenosis. Development of NVG was also shown to be associated with multiple pre-existing conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Treatment with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) may have a positive effect with regards to reduction of neovascularization glaucoma.[10] However, in this study, there was no significant difference in follow-up BCVA between NVG and non-NVG groups, with both groups yielding a poor prognosis.[45]

Ultimately, the overall mortality rate for patients with OIS is 40% at 5 years, with the leading cause of death being cardiovascular disease, primarily myocardial infarction (67%), with the second most common cause cerebral infarction (19%).[10] It is therefore essential that physicians adopt appropriate therapeutic options aiming at primary prevention of myocardial and cerebral infarction.

References

- ↑ Gordon N. Ocular manifestations of internal carotid artery occlusion. Brit J of Ophthal. May 1959;43(5):257-267.

- ↑ Hedges TR, Jr. Ophthalmoscopic findings in internal carotid artery occlusion. AJO. May 1963;55:1007-1012.

- ↑ Bullock JD et al. Ischemic ophthalmia secondary to an ophthalmic artery occlusion. AJO. Sep 1972;74(3):486-493.

- ↑ Biousse V. Carotid disease and the eye. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. Dec 1997;8(6):16-26.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Brown GC, Magargal LE. The ocular ischemic syndrome. Clinical, fluorescein angiographic and carotid angiographic features. International Ophthalmology. Feb 1988;11(4):239-251.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Kearns TP et al. The ocular aspects of bypass surgery of the carotid artery. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic. Jan 1979;54(1):3-11.

- ↑ Kearns TP et al. The ocular aspects of carotid artery bypass surgery. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1978;76:247-265.

- ↑ Brown GC. Macular edema in association with severe carotid artery obstruction. AJO. Oct 15 1986;102(4):442-448.

- ↑ Imrie FR et al. Bilateral ocular ischaemic syndrome in association with hyperhomocysteinaemia. Eye. Jul 2002;16(4):497-500.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Sivalingam A et al. The ocular ischemic syndrome. III. Visual prognosis and the effect of treatment. International Ophthalmology. Jan 1991;15(1):15-20.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Mizener JB et al. Ocular ischemic syndrome. Ophthalmology. May 1997;104(5):859-864.

- ↑ Sturrock GD, Mueller HR. Chronic ocular ischaemia. Brit J of Ophthalmol. Oct 1984;68(10):716-723.

- ↑ Klijn CJ et al. Venous stasis retinopathy in symptomatic carotid artery occlusion: prevalence, cause, and outcome. Stroke. Mar 2002;33(3):695-701.

- ↑ Ros MA et al. Ocular ischemic syndrome: long-term ocular complications. Annals of Ophthal. Jul 1987;19(7):270-272.

- ↑ Kerty E et al. Ocular hemodynamic changes in patients with high-grade carotid occlusive disease and development of chronic ocular ischaemia. II. Clinical findings. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. Feb 1995;73(1):72-76.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Costa VP et al. Collateral blood supply through the ophthalmic artery: a steal phenomenon analyzed by color Doppler imaging. Ophthalmology. Apr 1998;105(4):689-693.

- ↑ Choromokos EA, Raymond LA, Sacks JG. Recognition of carotid stenosis with bilateral simultaneous retinal fluorescein angiography. Ophthalmology. Oct 1982;89(10):1146-1148.

- ↑ Brown GC. Macular edema in association with severe carotid artery obstruction. AJO. Oct 15 1986;102(4):442-448.

- ↑ Utsugi N et al. Choroidal vascular occlusion in internal carotid artery obstruction. Retina. Dec 2004;24(6):915-919.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Mendrinos E et al. Ocular ischemic syndrome. Survey of Ophthalmology. Jan-Feb 2010;55(1):2-34.

- ↑ Story JL et al. The ocular ischemic syndrome in carotid artery occlusive disease: ophthalmic color Doppler flow velocity and electroretinographic changes following carotid artery reconstruction. Surgical Neurology. Dec 1995;44(6):534-535.

- ↑ Decarlo LJ. Ophthalmodynamometry: A Review. McGill Medical Journal. Oct 1961;30:134-140.

- ↑ Sisler HA. A review of ophthalmodynamometry. AJO. Sep 1960;50:419-424.

- ↑ Nederkoorn PJ et al. Duplex ultrasound and magnetic resonance angiography compared with digital subtraction angiography in carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review. Stroke. May 2003;34(5):1324-1332.

- ↑ Yuan C et al. Quantitative evaluation of carotid atherosclerotic plaques by magnetic resonance imaging. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. Sep 2002;4(5):351-357.

- ↑ Hankey GJ et al. Cerebral angiographic risk in mild cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. Feb 1990;21(2):209-222.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Luo J et al. Clinical analysis of 42 cases of ocular ischemic syndrome. J Ophthalmol. 2018;2018:2606147. Published 2018 Mar 11. doi:10.1155/2018/2606147

- ↑ Marx JL et al. Percutaneous carotid artery angioplasty and stenting for ocular ischemic syndrome. Ophthalmology. Dec 2004;111(12):[[1]].

- ↑ Foncea Beti N et al. The ocular ischemic syndrome. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. Dec 2003;106(1):60-62.

- ↑ Sivalingam A et al. The ocular ischemic syndrome. II. Mortality and systemic morbidity. International Ophthalmology. May 1989;13(3):187-191.

- ↑ Flaxel CJ, Larkin GB, Broadway DB, et al.(1997) Peripheral transscleral retinal diode laser for rubeosis iridis. Retina 17:421–429.

- ↑ Bloom PA, Tsai JC, Sharma K, et al.(1997) Cyclodiode: trans-scleral diode laser cyclophotocoagulation in the treatment of advanced refractory glaucoma. Ophthalmology 104:1508–1519.

- ↑ Barnett HJ et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. The New England Journal of Medicine. Nov 12 1998;339(20):1415-1425.

- ↑ North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial C. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. Aug 15 1991;325(7):445-453.

- ↑ Goldstein LB et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. Jun 20 2006;113(24):e873-923.

- ↑ Cohn EJ et al. Assessment of ocular perfusion after carotid endarterectomy with color-flow duplex scanning. Journal of vascular Surgery. Apr 1999;29(4):665-671.

- ↑ Ishikawa K et al. In situ confirmation of retinal blood flow improvement after carotid endarterectomy in a patient with ocular ischemic syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. Aug 2002;134(2):295-297.

- ↑ Neupert JR et al.(1976) Rapid resolution of venous stasis retinopathy after carotid endarterectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 81:600–602.

- ↑ Wong YM et al. The effects of carotid endarterectomy on ocular haemodynamics. Eye.1998;12:367–373.

- ↑ Costa VP et al. The effects of carotid endarterectomy on the retrobulbar circulation of patients with severe occlusive carotid artery disease. Ophthalmology. 1999;06:306–310

- ↑ Narins CR, Illig KA. Patient selection for carotid stenting versus endarterectomy: a systematic review. J of Vascular Surgery. Sep 2006;44(3):661-672.

- ↑ Neroev VV et al. Visual outcomes after carotid reconstructive surgery for ocular ischemia. Eye. Oct 2012;26(10):1281-1287.

- ↑ Sundt TM et al. Bypass surgery for vascular disease of the carotid system. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Mayo Clinic. Nov 1976;51(11):677-692.

- ↑ Haouas M et al. Évolution favorable d’un cas de syndrome d’ischémie oculaire chronique bilatéral traité en urgence par chirurgie de revascularisation carotidienne [Favorable outcome in a case of bilateral ocular ischemic syndrome treated by emergency carotid revascularization surgery]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie. 2015 Mar;38(3):e43-5. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2014.04.029. Epub 2015 Jan 15.

- ↑ Kim YH, Sung MS, Park SW. Clinical features of ocular ischemic syndrome and risk factors for neovascular glaucoma. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2017;31(4):343-350. doi:10.3341/kjo.2016.0067