Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (MGD)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is recognized by the following codes as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature:

- ICD-10:H02.89

- Short Description: Other specified disorders of eyelid

Disease

Meibomian glands or glandulae tarsales are large sebaceous glands in the eyelids that secrete lipids that form the superficial layer of tear film to protect against evaporation of the aqueous phase. These glands were first described in detail by German physician Heinrich Meibom (1638–1700) and were named after him (Fig 1).[1]

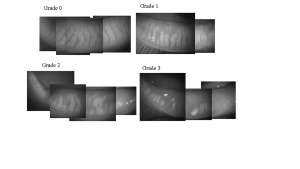

There are about 25–40 meibomian glands in the human upper eyelid and about 20–30 in the lower eyelid, with respective lengths of about 5.5 mm and 2 mm in Caucasian eyes.[2] [3]Each gland in the upper eyelid consists of clusters of about 10–15 secretory acini. These secrete lipid material through small ductules via a central duct at the lid margin, contributing to the outermost layer of the tear film.[4] The contraction of the orbicularis muscle during blinking and the contraction of Riolan muscle at the terminal part of the ductal system generates mechanical force that facilitates the secretion of meibum.[5] Meibum contains over 100 major individual complex lipids, over 90 proteins, and electrolytes.[6] [7] Aging, diet, sex hormones, systemic and ocular surface inflammatory disorders, usage of antibiotics, and primary dysfunction of Meibomian glands alters the composition of this mixture, resulting in altered tear film stability and function. Korb and Henriquez coined the term meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) in a study addressing contact lens intolerance and the obstruction of the Meibomian gland orifices by desquamated epithelial cells.[8] The International Workshop on MGD defined the disease as “a chronic, diffuse abnormality of the meibomian glands, commonly characterized by terminal duct obstruction and/or qualitative/ quantitative changes in the glandular secretion. It may result in alteration of the tear film, symptoms of eye irritation, clinically apparent inflammation, and ocular surface disease.”[9] Images of normal and progressive gland loss in patients with MGD are shown in Figure 2.[10]

Epidemiology

Meibomian gland dysfunction is an underdiagnosed and undertreated disease with asymptomatic disease being far more common than the symptomatic MGD.[11][12] It is estimated that 70% of Americans over the age of 60 have MGD.[13] The prevalence is lower among certain populations, ranging widely depending on the parameter looked at.[14][15] For example, prevalence may be 61.0–69.3% if based on telaniectasia in Asian populations, but it ranges from 3.5–19.9% among Caucasian populations. The prevalence increases with age and appears to be higher in males than in females.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for MGD include aging, deficiency of sex hormones (notably androgens), and systemic conditions such as Sjogren syndrome, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, psoriasis, atopy, polycystic ovary syndrome, and hypertension.[4][10][16] In addition, certain ophthalmic factors have been shown to impact Meibomian gland function, namely aniridia, chronic blepharitis, contact lens wear, eyelid tattooing, trachoma, and Demodex folliculorum infestation . Use of antibiotics, isotretinoin for acne, antihistamines, antidepressants, and hormone replacement therapy are found to be associated with MGD.

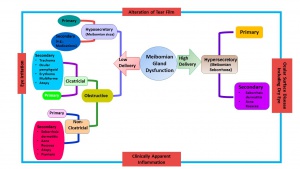

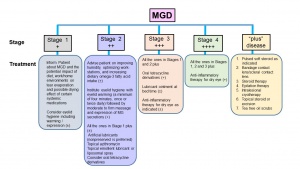

Classification

The MGD classification system proposed by the 2011 International Workshop on MGD is shown in Figure 3.[9] Meibomian gland dysfunction is classified based on the final consequence of dry eye diseases (DED) as low delivery or high delivery, which refers to the secretion status. Low delivery status is further classified into hyposecretory and obstructive conditions. Hyposecretion is due to decreased Meibomian gland function from gland atrophy or medications. Meibomian gland obstruction, the most common cause for hyposecretion, results from the hypertrophy of ductal epithelium and keratinization due to aging, decreased expression of androgen receptors, or medication use. Obstructive MGD can be further classified into cicatricial and noncicatricial. Hypersecretory MGD results from excessive secretion of lipids.

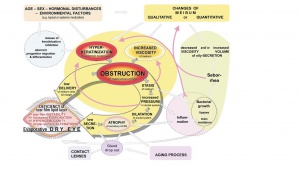

Pathophysiology

Meibomian gland dysfunction is a highly complex disease condition that is associated with or caused by a variety of host, microbial, hormonal, metabolic, or environmental factors. The pathways involved in the pathophysiology of MGD are shown in Figure 4 and take into consideration DED and MGD pathophysiologies.[4][17] Obstruction due to increased viscosity of meibum or hyperkeratinization meibomian gland ductal system leads to decreased secretion of meibum, affecting the tear film’s stability and leading to dry eyes.

A number factors can influence the physical and functional status of Meibomian glands, leading to loss of function, morphologic changes, atrophy, and gland drop out, including the aging process, alterations in sex hormones and the expression of their receptors, nutritional status, reduced eye blinking, medications, and infections or disease (e.g., seborrheic dermatitis).[13][16][18][19] Lid swabs after gland expression revealed that Staphylococcus aureus incidence was higher and coagulase-negative staphylococcus, corynebacterium, and streptococci incidence was lower in patients with MGD, both in mild and moderate-to-severe cases.[20] Significant alterations in the expression of up to 400 genes have also been reported in meibomian glands of individuals with MGD.[21] These changes impact the composition of meibum, leading to instability of the tear film.[22][23][24][25]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of MGD is based on examining the ocular surface and lid margin tear meniscus in association with altered anatomical features, such as terminal duct obstruction, gland drop out, qualitative and quantitative changes in meibum, and pathological events. The diagnostic subcommittee at the International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction recommend several approaches for diagnosing MGD-related disease.[26]

- Administer symptoms questionnaire (e.g., OSDI questionnaire)

- Measure blink rate and blink interval

- Measure lower tear meniscus height

- Measure tear osmolarity

- Assess epithelial cell damage with ocular surface staining (e.g., Oxford Grading System, Dry Eye WorkShop (DEWS) grading)

- Assess break-up times

- Tear break-up time (TBUT): Normal range 15–45 seconds

- Fluorescein break-up time (FBUT): Normal >10 seconds

- Noninvasive break-up time (NIBUT): Normal range 40–60 seconds

- Schirmer test: Normal <5 mm/5 min

- Symptoms assessment: Ocular surface disease index (OSDI) and dry eye questionnaire (DEQ)

- Measure of osmolarity

- Tear secretion test

- Measurement of tear volume

- Tear evaporation rate (evaporimetry)

- Corneal and conjunctival staining

- Tests to assess ocular inflammation

For asymptomatic disease, performing gland expression with digital pressure to the central lower lid followed by assessing ocular surface damage is recommended. Quantification for asymptomatic MGD (or symptomatic that has not been diagnosed with earlier tests) relies on morphologic lid features:

- Expressibility and quality of meibum

- Meibography: Document morphology using infrared or near infrared video cameras, confocal microscopy, or spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT)[3][10][27][28][29]

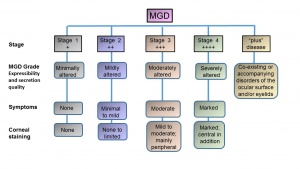

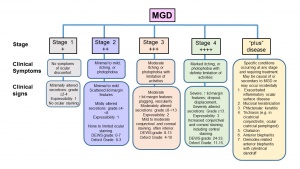

The presence of ocular surface damage or anatomical changes warrants meibomian gland functionality assessment. Staging of the disease, including clinical symptoms and signs, are shown in Figures 5 and 6. The stages are classified depending on expressibility and secretion quality, severity of symptoms, and corneal staining.

Clinical Management and Treatment

The recommended staged treatment algorithm for MGD is shown in Figure 7.[30]

Topical lubricants are advocated to relieve symptoms, reduce tear film evaporation, and stabilize lipids in tear film. However, lid hygiene and warm compresses or heat applications are the mainstay of the clinical management. Gentle massage and the application of heat to eyelids with warm compress (e.g., hot wet towel, heat masks) or devices (e.g., LipiFlow Thermal Pulsation System, MiBo Thermaflow, BlephEx, Intense Pulse Tx, KCL1100) help to liquify the meibum and prevent tear evaporation. Topical or systemic antibiotics can be used to control infections, and Demodex mite infestations can be treated with tea tree oil.[31] [32][33][34][35][36] This treatment algorithm was found to be effective 3 and 6 months post-treatment in a study of 108 subjects with DED and MGD.[37]

Medical therapy

Clinical Trial: Oral Azithromycin vs Doxycycline

A 2015 clinical trial of oral azithromycin vs doxycycline assessed the efficacy and safety of oral azithromycin compared to doxycycline in patients with MGD who had failed to respond to prior conservative management.[38]

Methods

One hundred ten patients (age >12 years) were randomly assigned to receive oral 5-day azithromycin (500 mg day 1, 250 mg/day thereafter) or 1-month doxycycline (200 mg/day). Patients had posterior blepharitis that had not responded to conservative management (4–5 minutes eyelid warming/massage/cleaning twice daily and artificial tears four times daily); all patients continued these conservative treatments during the course of the study. A score comprising 5 symptoms and 7 signs (primary outcome) was recorded before treatment and at 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months after treatment. Side effects were recorded, and overall clinical improvement was categorized as excellent, good, fair, or poor based on the percentage of change in the total score.

Main outcome measures

Symptoms and signs related to MGD.

Limitations

Absence of a control group without any systemic medication.

Results

Meibomian gland dysfunction symptoms and signs improved in both the azithromycin and the doxycycline groups. However, the azithromycin group showed a significantly better overall clinical response, with more improvement in bulbar conjunctival redness and ocular surface staining. The doxycycline group had significantly more side effects.

Conclusions

Although both oral azithromycin and doxycycline improved the symptoms of MGD, 5-day oral azithromycin is recommended for its better effect on improving the signs of MGD, better overall clinical response, and shorter duration of treatment.

Pearls for clinical practice

Oral 5-day azithromycin (500 mg on day 1 and then 250 mg/day) is a good option to treat MGD.

Surgical therapy

Surgical therapy may be indicated when secondary consequences of chronic MGD cause morbidity to the patients (e.g., multiple and/or recurrent chalaza, meibomian gland inversion, trichiasis, distichiasis, and (rarely) cicatricial entropion with keratopathy). Surgical procedures include incision and curettage or intralesional triamcinolone for subacute lesions, technical or electroepilation of symptomatic eyelashes, and surgical entropion correction for moderate-to-severe cicatricial entropion. Recurrences are not uncommon; realistic expectations should be emphasized to the patient.

Additional Resources

- Meibomian Glands. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/anatomy/meibomian-glands-list. Accessed March 18, 2019.

References

- ↑ Meibomius H. De vasis palpebrarum novis epistola: Muller, Helmstadt; 1666.

- ↑ Bron AJ et al. Meibomian gland disease. Classification and grading of lid changes. Eye (Lond) 1991;5 ( Pt 4):395-411.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Shirakawa R et al. Meibomian gland morphology in Japanese infants, children, and adults observed using a mobile pen-shaped infrared meibography device. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;155:1099-103 e1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Knop E et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the meibomian gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:1938-78.

- ↑ Linton RG et al. The Meibomian Glands: An Investigation into the Secretion and Some Aspects of the Physiology. Br J Ophthalmol 1961;45:718-23.

- ↑ Tsai PS et al. Proteomic analysis of human meibomian gland secretions. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:372-7.

- ↑ Shrestha RK et al. Analysis of the composition of lipid in human meibum from normal infants, children, adolescents, adults, and adults with meibomian gland dysfunction using (1)H-NMR spectroscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:7350-8.

- ↑ Korb DR, Henriquez AS. Meibomian gland dysfunction and contact lens intolerance. J Am Optom Assoc 1980;51:243-51.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Nelson JD et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:1930-7.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Arita R et al. Noncontact infrared meibography to document age-related changes of the meibomian glands in a normal population. Ophthalmology 2008;115:911-5.

- ↑ Viso E et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic meibomian gland dysfunction in the general population of Spain. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:2601-6.

- ↑ Yeotikar NS et al. Functional and Morphologic Changes of Meibomian Glands in an Asymptomatic Adult Population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:3996-4007.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chader GJ, Taylor A. Preface: The aging eye: normal changes, age-related diseases, and sight-saving approaches. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:ORSF1-4.

- ↑ Schaumberg DA et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on the epidemiology of, and associated risk factors for, MGD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:1994-2005.

- ↑ Foulks GN et al. Improving Awareness, Identification, and Management of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Ophthalmology 2012;119:S1-S12.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mantelli F et al. Effects of Sex Hormones on Ocular Surface Epithelia: Lessons Learned From Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Cell Physiol 2016;231:971-5.

- ↑ Baudouin C et al. Revisiting the vicious circle of dry eye disease: a focus on the pathophysiology of meibomian gland dysfunction. Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100:300-6.

- ↑ Uchino M et al. The features of dry eye disease in a Japanese elderly population. Optom Vis Sci 2006;83:797-802.

- ↑ Souchier M et al. Changes in meibomian fatty acids and clinical signs in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction after minocycline treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:819-22.

- ↑ Watters GA et al. Ocular surface microbiome in meibomian gland dysfunction in Auckland, New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016.

- ↑ Liu S et al. Changes in Gene Expression in Human Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2011;52:2727-40.

- ↑ McCulley JP, Shine WE. The lipid layer of tears: dependent on meibomian gland function. Exp Eye Res 2004;78:361-5.

- ↑ Shine WE, McCulley JP. Meibomian gland triglyceride fatty acid differences in chronic blepharitis patients. Cornea 1996;15:340-6.

- ↑ Shine WE, McCulley JP. Meibomianitis: polar lipid abnormalities. Cornea 2004;23:781-3.

- ↑ Joffre C et al. Differences in meibomian fatty acid composition in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction and aqueous-deficient dry eye. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:116-9.

- ↑ Tomlinson A et al. The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: Report of the Diagnosis Subcommittee. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2011;52:2006-49.

- ↑ Napoli PE et al. A Simple Novel Technique of Infrared Meibography by Means of Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography: A Cross-Sectional Clinical Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165558.

- ↑ Fasanella V et al. In Vivo Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy of Human Meibomian Glands in Aging and Ocular Surface Diseases. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:7432131.

- ↑ Liang QF et al. In vivo confocal microscopy evaluation of meibomian glands in meibomian gland dysfunction patients. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi 2016;52:649-56.

- ↑ Geerling G et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:2050-64.

- ↑ Wladis EJ et al. Intense Pulsed Light for Meibomian Gland Disease: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2020 Sep;127(9):1227-1233. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.009. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32327256.

- ↑ Greiner JV. A single LipiFlow(R) Thermal Pulsation System treatment improves meibomian gland function and reduces dry eye symptoms for 9 months. Curr Eye Res 2012;37:272-8.

- ↑ Zhao Y et al. Clinical Trial of Thermal Pulsation (LipiFlow) in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction With Preteatment Meibography. Eye Contact Lens 2016;42:339-46.

- ↑ Nam S et al. Evaluation of KCL 1100® Automated Thermodynamic System Treatment for Dry Eye with Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2016;57:5679.

- ↑ Connor CG et al. Clinical Effectiveness of Lid Debridement with BlephEx Treatment. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2015;56:4440-.

- ↑ Yeo S et al. Longitudinal Changes in Tear Evaporation Rates After Eyelid Warming Therapies in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction Tear Evaporation After Eyelid Warming. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2016;57:1974-81.

- ↑ Jackson C et al. Treatment Effects in a Norwegian Cohort of Dry Eye Patients with Meibomian Gland Dysfunction Following Treatment According to Guidelines of The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (2011): Three and Six Months Follow-up. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2016;57:5665.

- ↑ Kashkouli MB et al. Oral azithromycin versus doxycycline in meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomized double-masked open-label clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Feb;99(2):199-204. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305410. Epub 2014 Aug 19. PMID: 25138765.