Macular Hole

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Macular Hole ICD-9 code: 362.54

Disease

A macular hole (MH) is a retinal break commonly involving the fovea.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Idiopathic MH is the most common presentation. Risk factors include age, female gender, myopia, trauma, and ocular inflammation.

General Pathology

Different findings can be observed depending the stage of the MH. Residual cortical vitreous, retinal glial, and retinal pigment epithelial cells are often found on the retinal surface. They are thought to cause tangential traction on the fovea. Cystoid edema in the outer plexiform and inner nuclear layers and thinning of the photoreceptor layer can also be observed.

Pathophysiology

It has been hypothesized that MHs are caused by tangential traction as well as anterior posterior vitreoretinal traction of the posterior hyaloid on the parafovea. Macular holes are noted to be a complication of a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) at its earliest stages. They have been observed after anterior-segment laser procedures, possibly due to vitreoretinal traction.[1]

Risk Factors and Incidence

Macular holes are typically seen in patients aged ≥60 years, and women are more frequently affected than men. One study estimated the incidence rate of idiopathic MH to be 8.69 eyes per 100,000 population per year.[2] A careful history should be obtained to investigate for any of the risk factors mentioned above.

Primary Prevention

There are no preventative measures for idiopathic MHs. Pars plana vitrectomy has not been clearly demonstrated to be effective in preventing MH formation.

Diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis of MH is based on history and clinical exam, including slit lamp and dilated fundus examination. In some cases, optical coherence tomography (OCT) is useful for diagnosis and management. It is important to distinguish between a full-thickness MH vs a lamellar hole (irregular foveal contour with defect in the inner fovea) or pseudohole (an irregular foveal contour with steep edges without true absence of retinal tissue often associated with an epiretinal membrane).

Classification

There are 2 main classification schemes for MHs. Gass first described his clinical observations on the evolution of a macular hole as follows[3]:

- Stage 1 MH, or impending MH, demonstrates a loss of the foveal depression. A stage 1A MH is a foveolar detachment characterized a loss of the foveal contour and a lipofuscin-colored spot, while a stage 1B MH is a foveal detachment characterized by a lipofuscin-colored ring

- Stage 2 MH is defined by a full thickness break <400 µm in size. It might be eccentric with an inner layer “roof.” This can occur weeks to months after stage 1 MHs. A further decline in visual acuity is also noted. In most cases, the posterior hyaloid has been confirmed to be still attached to the fovea on OCT analysis.

- Stage 3 MH is further progression to a hole ≥400 µm in size. Nearly 100% of stage 2 MHs progress to stage 3 and the vision further declines. A grayish macular rim often denotes a cuff of subretinal fluid. The posterior hyaloid is noted to be detached over the macula with or without an overlying operculum (Figures 1 and 2)

- Stage 4 MH is characterized by a stage 3 MH with a complete PVD and a Weiss ring

In 2013, the International Vitreomacular Traction Study Group also formed a classification scheme of vitreomacular traction and macular holes based on OCT findings[4]:

- Vitreomacular adhesion: No distortion of the foveal contour; size of attachment area between hyaloid and retina defined as focal if ≤1500 microns and broad if >1500 microns

- Vitreomacular traction (VMT): Distortion of foveal contour present or there are intraretinal structural changes in the absence of a full-thickness MH; size of attachment area between hyaloid and retina defined as focal if ≤1500 microns and broad if >1500 microns

- Full-thickness macular hole (FTMH): Full-thickness defect from the internal limiting membrane (ILM) to the retinal pigment epithelium. Size is based on the horizontal diameter at narrowest point: small (≤250 μm); medium (250–400 μm); or large (>400 μm). The cause may be primary or secondary, and VMT may be present or absent

Other features to note on exam include yellow deposits at the base of the hole, retinal pigment epithelial changes at the base of the hole, and epiretinal membrane adjacent to the hole.

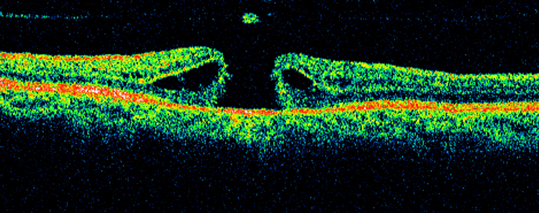

Figure 1: OCT image of an MH with an overlying operculum. The classic “anvil-shaped” deformity of the edges of the retina is noted due to intraretinal edema.

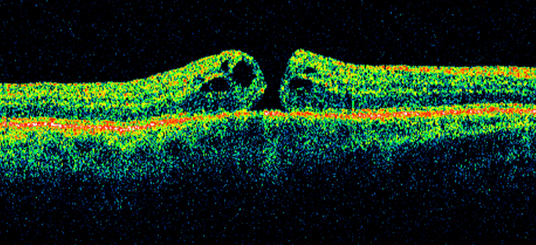

Figure 2: A small FTMH seen on OCT, with intraretinal and subretinal fluid.

Physical Examination

Slit lamp examination with special attention to the macula is important in the evaluation of MH (Figure 3). The Watzke-Allen sign can be used as a clinical test in cases of a suspected FTMH by shining a thin beam of light over the area of interest. The patient would perceive a “break” in the slit beam in cases of a positive test.

Careful examination of the fellow eye is also recommended, given that MHs are bilateral in up to 30% of patients.[5] Special attention should be paid to the vitreoretinal interface, involutional macular thinning, and retinal pigment epithelial window defects because these are risk factors for MH development in the fellow eye. Patients without a PVD in the fellow eye have an intermediate risk (up to 28%) of developing a MH,[6] whereas patients with a PVD are at low risk for developing an MH.

Figure 3: Clinical photo demonstrating an FTMH with a grayish macular rim suggestive of subretinal fluid. Note the retinal pigment epithelial changes at the base of the hole.

Signs

Depending on the stage of the MH, a subfoveal lipofuscin-color spot or ring can be noted. In more advanced cases, a partial or full-thickness macular break is observed.

Symptoms

Metamorphopsia (distortion of the central vision), central visual loss, or central scotoma may be reported.

Diagnostic Procedures

Fluorescein angiography (FA) demonstrates a hyperfluorescence pattern consistent with a transmission defect due to loss of xanthophyll at the base of the MH. However, FA is not usually necessary for diagnosis or management.

Optical coherence tomography is the gold standard in the diagnosis and management of MH. This high-resolution imaging system can allow for evaluation of the macula in cross-section and three-dimensionally, and can also be helpful for detecting subtle MHs as well as staging obvious ones.

As well, OCT can assist in the determination of whether there is an associated epiretinal membrane or if the posterior hyaloid is still attached, which can be critical in deciding on potential surgical treatments. It can also be used to aid in gauging the prognosis of the fellow eye.

Laboratory Tests

No laboratory tests are indicated in cases of idiopathic MHs.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical appearance of a MH is fairly distinctive. However, epiretinal membrane with a pseudohole, lamellar hole, and VMT must also be considered. Cystoid macular edema, subfoveal drusen, central serous chorioretinopathy, or adult vitelliform macular dystrophy also appear similar to a stage 1 MH.

Management

The clinical stage and duration of the MH is the most important issue in disease management.

Medical Therapy

In general, most stage 1 MHs can be followed conservatively, given the approximately 50% chance of spontaneous closure.[7] However, if the patient has symptomatic VMT or even an FTMH with associated VMT, one of the following treatment options may be considered:

- Ocriplasmin is a 27-kilodalton serine protease that essentially performs pharmacolytic vitreolysis, separating the hyaloid from the underlying retina. In the registration MIVI-TRUST clinical trials. at the day 28 post-injection time point, more eyes receiving intravitreal ocriplasmin exhibited release of the vitreoretinal attachment than eyes that received an intravitreal injection of drug vehicle (26.5% vs 10.1%); they were also more likely to experience MH closure (40.6% vs 10.6%, respectively).[8] There have been some rare adverse effects reported with ocriplasmin treatment, including electroretinography changes, lens subluxation, and dyschromatopsia

- More recently, some clinicians have found success in treating patients with a small bolus of injected intravitreal gas or air. Research studies are ongoing, but a few have reported success rates as high as 83% for FTMH closure.[9][10]

Medical Follow-up

Regardless of which medical treatment is used, the patient should be followed regularly. If the patient has an expansile gas placed in the eye, face-down positioning is often recommended for a short period of time, and it is important to remind the patient that they cannot fly or be at an elevation >2500 feet until the gas dissipates.

Surgery

Surgery involves a pars plana vitrectomy procedure with tamponade. This can be done with or without peeling of the ILM. A number of different instruments can be used to facilitate MH removal, including intraocular forceps, picks, and diamond-dusted instruments. Indocyanine green, Brilliant Blue, or triamcinolone acetonide are commonly used stains that assist in identifying the ILM, either by positive or negative staining.

Surgical techniques have been debated for many years. While most vitreoretinal surgeons agree that tamponade is important, the type of tamponade and duration of postoperative positioning are also critical. The importance of peeling the ILM with or without staining has also been debated. More recently, new techniques, including placing ILM flaps, neurosensory retinal grafts, amniotic membrane, platelet-rich plasma, autologous serum, perifoveal hydrodissection, or even lens capsules into larger holes, have been reported with success.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

Surgical Follow-up

In some patients, visual acuity improvement does not occur immediately. Visual improvement seems to be dependent on preoperative characteristics, duration of the MH, and other factors. Few postoperative instructions are as burdensome to our patients as face-down positioning after MH surgery. However, evidence from both recent studies and long-term clinical experience challenges this practice. A Cochrane Database review of 8 randomized controlled trials involving 709 eyes found no significant difference in MH closure rates between patients who maintained face-down positioning and those who did not.[17] Among patients with larger macular holes (≥400 μm), the closure rate was 94% in the face-down group compared with 84% in the non–face-down group. For smaller holes (<400 μm), the closure rate was 100% in the face-down group vs 96% in the non–face-down group. Therefore, the authors concluded that face-down positioning may have little or no effect on macular hole closure after surgery.

Similarly, in his 15-year review of MH repair without face-down positioning, Dr. Paul Tornambe reported a single-operation success rate of 92% in the non–face-down group and 90% in the face-down group.[18] Tornambe’s findings emphasize that the buoyancy of the gas bubble, rather than strict positioning, is key to isolating the MH and promoting healing. He noted that patients who avoided face-down positioning experienced similar anatomic success rates, with the added benefit of reduced discomfort and improved quality of life.

The impact of this myth extends beyond patient discomfort to affect surgical decision-making and resource allocation. Many elderly or physically limited patients may be denied surgery based on concerns about positioning compliance, while others may require extended stays in skilled nursing facilities solely to ensure adherence. The evidence suggests that modified positioning regimens can achieve equivalent results, reducing the burden on patients and healthcare systems.

Surgical Complications

Complications are similar to those seen in all eyes undergoing pars plana vitrectomy. In particular, these eyes are at a higher risk of retinal tear and detachment. The vitreous is the most adherent to the optic nerve, macula, and vitreous base. Patients with MHs may inherently have an abnormal vitreoretinal interface, and thus during certain portions of vitrectomy may have a higher risk for development of retinal tears or retinal detachment. Concurrent rhegmatogenous retinal and choroidal detachments, in combination with MHs, are characterized by exceptional hypotony and poor vision.[19]

Surgical Prognosis

The visual outcomes following pars plana vitrectomy are very favorable. In general, better preoperative visual acuity results in better postoperative visual acuity. However, eyes with worse preoperative visual acuity often experience the greatest absolute postoperative improvement. A small number of MHs can recur after a successful closure with initial surgery.[20]

Additional Resources

- Boyd K, Vemulakonda GA. What is a macular hole? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye Health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/macular-hole-list. Published October 31, 2024. Accessed June 9, 2025.

- AAO PPP Retina/Vitreous Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Idiopathic macular hole PPP 2024. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/education/preferred-practice-pattern/idiopathic-macular-hole-ppp. Published February 2025. Accessed June 9, 2025.

References

- ↑ Tsui JC, Marks SJ. Unilateral stage 1A macular hole secondary to low-energy Nd:YAG peripheral iridotomy. Cureus. 2021;13(1):e12603.

- ↑ McCannel CA, Ensminger JL, Diehl NN, et al. Population based incidence of macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(7):1366-1369.

- ↑ Gass JD. Idiopathic senile macular hole. Its early stages and pathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(5):629-639.

- ↑ Duker JS, Kaiser PK, Binder S, et al. The International Vitreomacular Traction Study Group classification of vitreomacular adhesion, traction, and macular hole. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(12):2611-2619.

- ↑ McDonnell PJ, Fine SL, Hillis AI. Clinical features of idiopathic macular cysts and holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93(6):777-786.

- ↑ Trempe CL, Weiter JJ, Furukawa H. Fellow eyes in cases of macular hole: biomicroscopic study of the vitreous. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104(1):93-95.

- ↑ la Cour M, Friis J. Macular holes: classification, epidemiology, natural history and treatment. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80(6):579-587.

- ↑ Stalmans P, Benz MS, Gandorfer A, et al. Enzymatic vitreolysis with ocriplasmin for vitreomacular traction and macular holes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):606-615.

- ↑ Chan CK, Mein CE, Crosson JN. Pneumatic vitreolysis for management of symptomatic focal vitreomacular traction. Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12(4):419-423.

- ↑ Jorge R, Costa RA, Cardillo JA, et al. Optical coherence tomography evaluation of idiopathic macular hole treatment by gas-assisted posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(5):869-871.

- ↑ Nawrocki J, Bonińska K, Michalewska Z. Managing optic pit. The right stuff! Retina. 2016;36(12):2430-2432.

- ↑ Liggett PE, Skolik DS, Horio BS, et al. Human autologous serum for the treatment of full-thickness macular holes. A preliminary study. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1071-1076.

- ↑ Konstantinidis A, Hero M, Nanos P, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelets in macular hole surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:745-750.

- ↑ Chen SN, Yang CM. Lens capsular flap transplantation in the management of refractory macular hole from multiple etiologies. Retina. 2016;36(1):163-170.

- ↑ Grewal DS, Mahmoud TH. Autologous neurosensory retinal free flap for closure of refractory myopic macular holes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(2):229-230.

- ↑ Meyer CH, Borny R, Horchi N. Subretinal fluid application to close a refractory full thickness macular hole. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2017;3:44.

- ↑ Cundy O, Lange CA, Bunce C, et al. Face-down positioning or posturing after macular hole surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;11(11):CD008228.

- ↑ Tornambe PE. Macular hole repair without face-down positioning. Retina Today. https://retinatoday.com/articles/2010-sept/macular-hole-repair-without-face-down-positioning. Published September 2010. Accessed June 9, 2025.

- ↑ Tsui JC, Brucker AJ, Kolomeyer AM. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with concurrent choroidal detachment and macular hole formation after uncomplicated cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation: a case report and review of literature. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2024;18(2):168-172.

- ↑ Abbey AM, Van Laere L, Shah AR, et al. Recurrent macular holes in the era of small-gauge vitrectomy: a review of incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Retina. 2017;37(5):921-924.