Corneal Cross-Linking

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

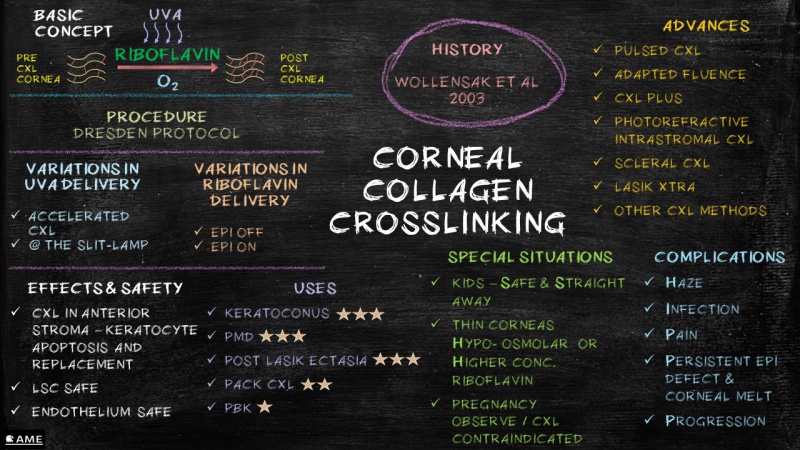

Corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) is a minimally invasive procedure used to prevent progression of corneal ectasias such as keratoconus and post-LASIK ectasia.

Background

Collagen cross-linking refers to the ability of collagen fibrils to form strong chemical bonds with adjacent fibrils. In the cornea, collagen cross-linking occurs naturally with age due to an oxidative deamination reaction that takes place within the end chains of the collagen. It has been hypothesized that this natural cross-linkage explains why keratectasia (corneal ectasia) often progresses most rapidly in adolescence or early adulthood but tends to stabilize in patients after middle-age. While cross-linking tends to occur naturally over time, there are other pathways that may lead to premature cross-linking. Glycation, a reaction seen predominantly in people with diabetes, can lead to the formation of additional bonds between collagen. Oxidation has also been shown to trigger corneal cross-linkage through the release of oxygen free radicals.

The bases for the currently employed CXL techniques were developed by researchers at the University of Dresden in the late 1990s, who used UV light to induce collagen cross-linking via the oxidation pathway in riboflavin-soaked porcine and rabbit corneas. The resultant corneas were stiffer and more resistant to enzymatic digestion. This investigation proved that treated corneas contained higher molecular weight polymers of collagen due to fibril cross-linking, and safety studies showed that the corneal endothelium was not damaged by the treatment if proper UV irradiance was maintained and if the corneal thickness exceeded 400 µm.[1]

Human studies of UV-induced corneal cross-linking began in 2003 in Dresden, with promising early results. The initial pilot study enrolled 16 patients with rapidly progressing keratoconus, all of whom stopped progressing after CXL treatment. Additionally, 70% of the patients experienced flattening of steep anterior corneal curvatures (decreases in average and maximum keratometric values), and 65% had an improvement in visual acuity. There were no reported complications.[2]

In late 2011, the FDA awarded orphan drug status to Avedro for its formulation of riboflavin ophthalmic solution to be used in conjunction with the company's UVA irradiation system. Corneal CXL using riboflavin and UV light received FDA approval on April 18, 2016.

Basic Concepts

Cross-linking relies on a photosensitizer and a UV light source, which together produce a photochemical reaction.

Riboflavin

A photosensitizer is a molecule that absorbs light energy and produces a chemical change in another molecule. In CXL, the photosensitizer is riboflavin, with an absorption peak of 370 nm. Riboflavin is a systemically safe molecule that can be adequately absorbed by the corneal stroma through topical application.

UV Light

UV-A light was found to be ideal for stimulating a photosensitive reaction with riboflavin while at the same time protecting other ocular structures.[3] The total fluence required for CXL with UV-A light is 5.4J/cm2. According to the Bunsen–Roscoe law, the effect of a photochemical reaction should be similar if the total fluence remains constant. Thus, various protocols have been devised using different combinations of intensity and duration of UV-A exposure for CXL.[4] However, it has been noted that CXL fails to be effective once the energy intensity exceeds 45 mW/cm2.

Photochemical Reaction

Once exposed to UV-A light, riboflavin generates reactive oxygen species, which induce the formation of covalent bonds between adjacent collagen molecules and between collagen molecules and proteoglycans.[5] The presence of oxygen is essential for this process.[5]

Patient Selection

Indications

The primary purpose of cross-linking is to halt the progression of ectasia. Therefore, ideal candidates for this therapy are individuals with a progressive ectatic disease of the cornea. The most common indication is keratoconus, but other indications may include pellucid marginal degeneration, Terrien marginal degeneration, or post–refractive surgery ectasia (e.g., LASIK, photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), or radial keratotomy). While there are currently no definitive progression criteria for CXL, parameters to consider include changes in refraction (including astigmatism), uncorrected visual acuity, best corrected visual acuity, and corneal shape (topography and tomography).

Contraindications

- Corneal thickness <400 µm

- Prior herpetic infection (due to the possibility of viral reactivation)

- Concurrent infection

- Severe corneal scarring or opacification

- History of poor epithelial wound healing

- Severe ocular surface disease (e.g., dry eye)

- Autoimmune disorders

Surgical Technique

The standard treatment protocol, called the Dresden protocol, was formulated by Wollensak et al. for corneas with minimal thickness of 400 µm. The general steps are as follows:[2]

- Instill topical anesthetic drops in the eye

- Debride the central 7–9 mm of corneal epithelium

- Instill 0.1% riboflavin 5-phosphate drops and 20% dextran solution every 5 minutes for 30 minutes

- Simultaneously expose to UV-A light (370 nm, 3 mw/cm2) for 30 minutes

- Conclude with the application of topical antibiotics and soft BCL with good oxygen permeability

This video demonstrates these steps, showing how anesthetic drops are given and the speculum is placed, followed by the removal of the epithelium, administration of riboflavin, and UV exposure.

Variations in Surgical Technique

Riboflavin

Delivery

- Epithelium-off method: As the corneal epithelium offers a barrier to the diffusion of riboflavin to the stroma, the epithelium is manually debrided to enable better penetration. The epithelium-off method is the standard method used for CXL and remains the most effective.[4]

- Epithelium-on method (trans-epithelial method): Various techniques have been tried to avoid epithelium debridement. These include the use of pharmacological agents to loosen the intra-epithelial junctions, the creation of intrastromal pockets for direct introduction of riboflavin, and iontophoresis. Even though debridement-induced complications like postoperative pain and corneal haze are avoided, studies thus far have demonstrated lower effectiveness with this method than with epithelium-on CXL.[5]

Osmolarity

Hypo-osmolar riboflavin is used in thin corneas (320–400 µm) to thicken the cornea to a minimum of 400 µm.[6]

UV Exposure

Treatment Time - Accelerated CXL

Several protocols have been developed to reduce the treatment time by increasing the intensity of UV exposure. Studies have shown that a middle path with an irradiation dose of 10 mW/cm2 for 9 minutes has a better therapeutic and safety profile than higher irradiation doses for shorter periods of time.[5]

Positioning

Traditionally, CXL is performed in the supine position, though there are few reports on the nuances of CXL performed upright at the slit lamp.[7]

Effects and Safety

Cross-linking effects are seen largely in the anterior cornea, as riboflavin concentration diminishes with increasing depth.

- The debrided epithelium is replaced in 3–4 days

- Limbal stem cells are not damaged, as riboflavin is kept away by the remaining peripheral epithelium

- The subepithelial basal nerve plexus is obliterated; however, it starts to regenerate after 7 days

- Apoptosis of keratocytes in the anterior stroma occurs, but in the weeks following CXL, new keratocytes migrate inward from the periphery

- As the stroma heals, collagen compaction and a hyper-dense extracellular matrix are seen

- When correctly performed, CXL does not cause any endothelial damage

Cross-linking has been shown to alter normal corneal structure and cellularity at least for 36 months.[6] Intraocular pressure measurements are not significantly affected.

Cross-linking Applications

Keratoconus

Controversies exist as to when is the best time to perform CXL for keratoconus, though given the natural history of the disease, it is prudent to perform CXL when progression is documented. Patients with keratoconus must also be advised to stop eye-rubbing and to avoid specific sleeping positions, as those factors appear to play a major role in disease progression.

To promote visual rehabilitation as well as stabilize keratoconus, several different approaches that combine CXL with refractive surgery (e.g., CXL Plus) have been described. The Athens protocol (Kanellopoulos et al) involves performing topography-guided PRK immediately followed by corneal CXL. Cross-linking with intracorneal stromal rings (INTACS) or phakic IOL are additional techniques that can be employed to improve both best-corrected and uncorrected visual acuity.[4][8]

Pellucid Marginal Degeneration

Pellucid marginal degeneration is a rare ectatic disorder usually involving the inferior peripheral cornea. Cross-linking has been attempted in eyes affected by this condition by decentering the focus of irradiation to involve the pathological site. Reports suggest improvements in visual acuity, keratometry, and astigmatism parameters. While long-term stability has yet to be studied, in the absence of serious complications, CXL does appear to buy time for these patients and postpone further tectonic surgical interventions.[3][9]

Ectasia Following Refractive Surgery

Cross-linking for post-LASIK ectasia can stabilize or improve visual acuity and keratometric parameters. The Athens protocol is one such procedure, combining CXL with PRK. LASIK Xtra is another procedure in which LASIK is followed by modified CXL with the goal of preventing post-LASIK ectasia. However, there is limited evidence regarding the benefit, safety, and stability of this approach.[3][8][9]

Photo-activated Chromophore for Infectious Keratitis (PACK) Corneal CXL

Strengthening of the cornea by CXL and the microbicidal activity of UV irradiation have been utilized successfully in the management of keratitis with stromal melt. As the consistency of results is yet to be demonstrated, CXL is currently considered only in cases resistant to standard antimicrobial therapy.[8]

Bullous Keratopathy

Cross-linking has been shown to reduce corneal edema and thickness with improvement in visual acuity in patients with bullous keratopathy. However, these changes appear to last for only about 6 months; due to this transient effect, CXL may only have a palliative role for this condition.[9]

Studies and Trials

C.G. Carus University Hospital, Dresden, Germany Study [10]

The strength of this study is its large sample size at 1 year. However, poor definition of the disease being treated and poor sample size after 1 year are weaknesses.

- Enrolled 480 eyes of 272 patients

- 241 eyes had ≥6 months data post-CXL, 33 eyes had ≥3 years data post-CXL

Definition of progression: ≥1D change in keratometry value over 1 year; or need for a new contact lens fit ≥1 in 2 years; or "patient reports of decreasing visual acuity"

Results:

- Significant improvement in BCVA at 1 year (-0.08 logMAR BCVA) and 3 yrs (-0.15 logMAR BCVA)

- Significant decrease in mean keratometry in 1st year (-2.68D)

- 53% of eyes with ≥1 line improvement in BCVA 1st year; another 20% stable in 1st year

- 87% of eyes stable or improved at 3 yrs (though low numbers of participants in this analysis limits the ability to draw conclusions)

Siena Eye Cross Study [11]

Similar to the Dresden study, this study is strengthened by its large sample size at 1 year, but interpretation and application to a wider set of patients is limited by a poorly defined patient population and the small sample size seen at 4 years.

- Enrolled 363 eyes with progressive keratoconus

- 44 eyes had ≥48 months of data post-CXL

Definition of progression: Only states that disease was defined "clinically and instrumentally within 6 months"

Results:

- Significant improvement in manifest spherical equivalent at 1 year (+1.62D) and 4yrs (+1.87D)

- Significant decrease in mean keratometry by 1 year (-1.96D) and 4 years (-2.26D)

- No significant change in pachymetry, UCVA/BCVA, or cylinder values

Australian Study [12]

This study had the best published study design and definition of progression of the three discussed thus far. All patients had clearly defined progressive keratoconus and were followed for 5 years. The 3-year data was published in April 2014 and is described below.[13] The 5-year data were reported to be very similar (relayed via personal communication with one of the authors) but were not published. Recruitment ended in 2009 with 50 control eyes and 50 treatment eyes.

Definition of progression (all over 12 months): Increase in cylinder on manifest refraction by ≥1D; or increase in steepest keratometry value (on Sim K or Manual) by ≥1D; or decrease in back optic zone radius of best-fitting contact lens by >0.1 mm

Methods:

- Eligible eyes were randomized independently to either CXL or control group

- Primary outcome measure: maximum simulated keratometry value (Kmax)

- Secondary outcome measures: uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best spectacle-corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), spherical and cylindrical error on manifest refraction, spherical equivalent, minimum simulated keratometry value (Kmin), corneal thickness at thinnest point, endothelial cell density, and intraocular pressure

- Assessments were performed at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Treatment: Dresden Protocol (epi-off) – Riboflavin 0.1% drops applied (after epithelial removal with a 57 Beaver blade) every 1–3 minutes for 15 minutes and continued every 1–3 minutes as needed over the 30-minute UV-exposure period. UV-X device delivered UV-A 370 nm at 3.0 mW/cm2 through a 9 mm aperture at a distance of 50 mm from the corneal apex.

- Control eyes did not receive sham. At 6 months, compassionate treatment with CXL was allowed in control eyes, but this then excluded patients from the remainder of the study. Therefore, final results are comparing only treated vs untreated eyes.

Results:

- Out of the 49 control eyes, 12 underwent CXL and 5 had corneal transplantation. Five treated eyes and 4 control eyes were withdrawn for patient personal reasons. The results are not described by an intention to treat analysis (ITT), so the data after drop-out or crossover on the study patients is not included in the reported results.

- Primary outcome results: Significant difference in Kmax at all time points.

- Treated: Average Kmax flattening was -1.03 D. Six eyes (13%) flattened by ≥ 2.0 D; 1 eye steepened by ≥2.0 D. There was a negative correlation between baseline Kmax and change in Kmax at 36 months, with the greatest improvement in eyes having a baseline Kmax ≥ 54.0 D.

- Control: Average Kmax steepening was +1.75 D. No eyes flattened by ≥2.0 D; 19 eyes (39%) steepened by ≥2.0 D. There was a negative correlation between patient age at enrollment and change in Kmax.

- Secondary outcome results:

- UCVA: Improved in treatment group compared to baseline at 12, 24, and 36 months (p < 0.001). Worsened in control group at 36 months (p < 0.001).

- BSCVA: Improved in treatment group compared to baseline at 12, 24, and 36 months (p < 0.007). No significant change in control group at 36 months or between treated and control eyes at any time point.

- Manifest spherical refraction: No significant difference at any time point.

- Manifest cylindrical error: No significant change from baseline in treatment group.

- Corneal thickness at thinnest point on ultrasound: No significant change in treatment group at any time point. Decreased in control group at 36 months (p = 0.029).

- Corneal thickness at thinnest point on Orbscan: Treatment group showed significant decrease, most marked at 3 months (-93.00 µm, p < 0.001). This reversed over the 36-month follow-up period to -19.52 µm. Control group showed progressive decreases at 12, 24, and 36 months (p < 0.001).

- Intraocular pressure: No significant change using Tonopen in either group. Using Goldmann applanation tonometer, significant decreases at 36 months in both groups but no significant differences between groups.

- Adverse Events:

- Keratitis and corneal edema: 1 case. Authors attributed this to premature resumption of rigid gas permeable lens wear; while it did not adversely affect outcome, it did cause a scar.

- Keratitis and iritis: 1 case. Started 2 days after treatment and presumed to be microbial keratitis. Resolved on ofloxacin and fluorometholone acetate 0.1%. Culture negative.

- Peripheral corneal neovascularization: 1 case. Noted at 36 months and attributed to acne rosacea and not CXL.

- Haze: All patients had some degree of haze, and this resolved with time.

Conclusions:

The authors concluded that "CXL should continue to be considered as a treatment option for patients with progressive keratoconus" but that "despite the growing body of literature and continuing efforts to optimize the treatment protocol, there remains a lack of randomized controlled studies with longer-term follow-up to support the widespread clinical use of CXL for keratoconus."

US Multicenter Clinical Trials (AVEDRO)[14][15]

The unique strength of the Avedro studies, NCT00674661 and NCT00647699, was the presence of an actual sham control group. However, the corneal epithelium was not removed in the sham control groups. Patients in the sham control groups were allowed to cross over to CXL treatment after the 3-month evaluation point, which left very few patients in each control group at the end of the study. The definition of progressive disease was not as rigorous as in the Australian study, but it was more clearly defined than most other reported randomized concentration-controlled trials. Eleven US sites were included.

- US Multicenter clinical trial of corneal CXL for keratoconus treatment: 204 eyes enrolled

- US Multicenter clinical trial of corneal CXL for treatment of corneal ectasia after refractive surgery: 178 eyes enrolled

- Eyes of patients aged ≥14 years with progressive keratoconus or corneal ectasia after refractive surgery (defined as one or more of the following: increase in 1D in steepest keratometry; or increase of 1D or more in manifest cylinder; or increase of 0.5D or more in spherical equivalent in manifest refraction over a 24-month period) were randomized to either CXL treatment (Dresden protocol) or sham (application of riboflavin but no epithelial debridement or UV light treatment)

- Primary outcome measure: Change in maximum keratometry value over a 1 year period

Results:

- In the CXL treatment groups, Kmax decreased by 1.6 D in the progressive keratoconus group and by 0.7 D in the corneal ectasia post–refractive surgery group from baseline to 1 year. Kmax decreased by ≥2 D in ~30% of patients with progressive keratoconus and in ~20% of patients with corneal ectasia post–refractive surgery; it increased by ≥2 D in ~5% of CXL treatment groups for progressive keratoconus and corneal ectasia post–refractive surgery.

- Disease continued to progress in the control groups of both studies.

- About a third of the CXL-treated eyes in both studies gained some corrected visual acuity; about 5% of CXL-treated eyes lost some corrected visual acuity.

- The most frequent adverse event in both studies was corneal haze.

- No significant changes were noted in endothelial cell count 1 year after treatment in both studies.

Conclusions:

The authors conclude: "These trials demonstrated the efficacy and safety of CXL for the treatment of keratoconus/corneal ectasia. In addition to decreasing disease progression, CXL also can have beneficial visual and optical effects such as decrease in corneal steepness and improvement in visual acuity in some patients."

Complications

- Temporary stromal edema (up to 70%), temporary haze (up to 100%), and permanent haze (up to 10%)

- Corneal scarring and sterile infiltrates[16][17]

- Infectious keratitis (bacterial/protozoan/herpetic) [18][19][20]

- Diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) in a post-LASIK patient[21]

Special Situations

Pediatric Keratoconus

Keratoconus in children tends to be aggressive and is usually associated with an unfavorable prognosis and an increased need for a corneal transplant. Hence, in this age group, CXL is advised immediately without the need for documenting progression. The Siena Paediatrics CXL study, conducted in 152 patients with keratoconus aged 10–18 years, demonstrated rapid functional improvement after CXL and better long-term stability irrespective of initial corneal thickness in 80% of patients. As expected, patients with thicker corneas did better than the patients with thinner corneas.[4][9]

Thin Cornea

According to the Dresden protocol, the minimal corneal thickness for CXL is 400 µm. However, many cases of keratoconus have thin corneas, so various modifications have been tried to safely cross-link these eyes.

In corneas with a minimum thickness of 350 µm, hypo-osmolar riboflavin solution has been used to induce corneal swelling. The CXL effect is not compromised, as the anterior stroma remains the same while the posterior corneal stroma swells considerably, which in turn protects the endothelium. Prior to the advent of hypo-osmolar riboflavin, other methods like reducing the UV irradiation intensity and avoiding debriding of the central epithelium were tried; however, CXL effectiveness was compromised.

Greater riboflavin concentrations (>0.2%) have also been tried in an attempt to increase the UV absorption in the anterior stroma and hence protect the endothelium.[6]

Corneal Ectasia in Pregnancy

Pregnancy is associated with hormonal changes that can negatively impact corneal biomechanics. Hence it is advisable to closely monitor pregnant patients with keratoconus or recent refractive surgery. While cross-linking is avoided during pregnancy, due to the possibility of complications that may require systemic therapy or additional procedures, it may be done after delivery. Even if CXL is performed, these patients need to be informed that the ectasia may progress during subsequent pregnancy due to the associated hormonal changes. For the same reason, it would be prudent for these patients to avoid hormonal contraception methods.[9]

Advances in CXL

Pulsed CXL

It has been postulated that pulsed delivery of UVA radiation would permit better oxygen diffusion into the stroma. As oxygen has an essential role in the CXL photochemical reaction, the presence of more oxygen may translate to greater effect. Further studies are required to determine the ideal pulsing protocols.[8]

Adapted Fluence

Thus far, UV-A fluence delivery has remained constant at 5.4J/cm2 irrespective of the CXL protocol. However, Hafezi and Kling introduced the concept of adapted fluence, in which the energy delivered is customized for the cornea. While this approach may increase the safety profile of CXL in some cases, especially thin corneas, it remains to be validated.[8]

LASIK Xtra

LASIK Xtra is a procedure in which CXL is combined with LASIK. After raising the flap and performing laser ablation, higher concentration riboflavin (0.25%) is applied to the stromal bed for about 90 seconds. After this, the interface is washed and flap replaced. Then, half-fluence high-intensity UV irradiation is performed. Results so far have shown promise, with better refractive stability and reduced incidence of post-LASIK regression and ectasia.[8]

Photorefractive Intrastromal CXL

High‑fluence CXL has also been tried in patients with low myopia to induce subsequent flattening and refractive correction.[8]

Scleral CXL in Axial Myopia

Progressive myopia is accompanied by scleral thinning and elongation. In vitro studies are being conducted to determine whether cross-linking the sclera may be able to stall the progression of this disease.[8]

Other CXL Methods

Photochemical CXL (with agents such as rose bengal dye or photosynthetic-agent derivatives like chlorophyll) and purely chemical CXL (using molecules like Genipin and β-nitro alcohols) have been investigated. Contact lens–assisted cross-linking (CACXL) has also been suggested, which uses a contact lens in thin corneas to increase the corneal thickness.[3]

Summary

References

- ↑ P T Ashwin, P J McDonnell. Collagen cross-linkage: a comprehensive review and directions for future research. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:965e970.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-a-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 May;135(5):620-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Sorkin N, Varssano D. Corneal Collagen Crosslinking: A Systematic Review. OPH. 2014;232(1):10-27. doi:10.1159/000357979

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Randleman JB, Khandelwal SS, Hafezi F. Corneal cross-linking. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015;60(6):509-523. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.04.002

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Subasinghe SK, Ogbuehi KC, Dias GJ. Current perspectives on corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(8):1363-1384. doi:10.1007/s00417-018-3966-0

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Raiskup F, Spoerl E. Corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet A. I. Principles. Ocul Surf. 2013;11(2):65-74. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2013.01.002

- ↑ Salmon B et al. CXL at the Slit Lamp: No Clinically Relevant Changes in Corneal Riboflavin Distribution During Upright UV Irradiation. J Refract Surg. 2017;33(4):281.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Sachdev GS, Sachdev M. Recent advances in corneal collagen cross-linking. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017;65(9):787. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_648_17

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Raiskup F, Spoerl E. Corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet A. Part II. Clinical indications and results. Ocul Surf. 2013;11(2):93-108. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2013.01.003

- ↑ Raiskup-Wolf F, Hoyer A, Spoerl E, Pillunat LE. Collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A light in keratoconus: long-term results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008 May;34(5):796-801.

- ↑ Caporossi A et al. Long-term results of riboflavin ultraviolet a corneal collagen cross-linking for keratoconus in Italy: the Siena eye cross study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010 Apr;149(4):585-93. Epub 2010 Feb 6.

- ↑ Wittig-Silva, C et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Corneal Collagen Cross-linking in Progressive Keratoconus: Preliminary Results. Journal of Refractive Surgery. 2008 (24): S720 - S725.

- ↑ Wittig-Silva C et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Corneal Collagen Cross-linking in Progressive Keratoconus: Three-Year Results. Ophthalmology. 2014. Volume 121 (4); 812-821.

- ↑ Hersh PS et al; United States Crosslinking Study Group. United States Multicenter Clinical Trial of Corneal Collagen Crosslinking for Keratoconus Treatment. Ophthalmology. 2017 Sep;124(9):1259-1270. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.03.052. Epub 2017 May 7. Erratum in: Ophthalmology. 2017 Dec;124(12):1878. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.014. PMID: 28495149.

- ↑ Hersh PS et al; U.S. Crosslinking Study Group. U.S. Multicenter Clinical Trial of Corneal Collagen Crosslinking for Treatment of Corneal Ectasia after Refractive Surgery. Ophthalmology. 2017 Oct;124(10):1475-1484. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.036. Epub 2017 Jun 24. PMID: 28655538.

- ↑ Mazzotta C et al. Stromal haze after combined riboflavineUVA corneal collagen cross-linking in keratoconus: in vivo confocal microscopic evaluation. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2007;35:580e2.

- ↑ Koller T et al. Complication and failure rates after corneal crosslinking. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009 Aug;35(8):1358-62.

- ↑ Pollhammer M, Cursiefen C. Bacterial keratitis early after corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35:588e9.

- ↑ Rama P et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis with perforation after corneal crosslinking and bandage contact lens use. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35:788e91.

- ↑ Kymionis GD et al. Herpetic keratitis with iritis after corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet A for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007;33:1982e4.

- ↑ Kymionis GD et al. Diffuse lamellar keratitis after corneal crosslinking in a patient with post-laser in situ keratomileusis corneal ectasia. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007;33:2135e7.