Complications of Hyaluronic Acid Fillers

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers are used in the periocular area, along with many other locations, for both aesthetic rejuvenation and to treat certain functional disorders.[1] These fillers are effective and are generally well tolerated, but complications do arise.[1] Over 90% of adverse events from the use of HA fillers are mild and transient; these adverse events include injection site redness, swelling, and bruising. However, disastrous outcomes can occur, including necrosis, vision loss, and cerebrovascular accidents.[1] In cases of HA filler–related complications, certain treatments can be attempted, such as hyaluronidase, massage, and hyperbaric oxygen.[2] This article discusses the complications of HA fillers, along with methods for prevention and management.

Complications

Hematoma

One of the most common complications associated with HA fillers is bruising, which usually occurs immediately after puncture of periocular vessels.[3] It can also sometimes be delayed due to external stretch from swelling secondary to the highly hygroscopic nature of HA.[3] If the physician notices bleeding from injection, immediate direct pressure can reduce hematoma size. Another possible method that has been suggested for reducing the likelihood of hematoma formation is stopping antithrombotic agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antiplatelet medications; however, this is controversial due to the inherent risk of embolism or thrombosis.[1]

Of note, homeopathic arnica has been suggested to expedite healing from bruising, but this is not recommended. In short, this is because the nature of homeopathy depends on two illogical concepts: (1) that the “drug” being sold is actually so dilute that it is not actually present in the treatment container; and (2) the ingredient being sold has an action that is opposite to the one desired. For example, arnica is actually a toxic herb. Regardless, despite the extreme dilution, this controversial idea can still be dangerous if use of the homeopathic substance slows the patient from obtaining true medical care or if the ingredients in the bottle are either not diluted properly or packaged with other toxic ingredients.

Early-Onset Nodules and Lumps

Another undesirable event that can arise is the development of lumps and nodules, which can result from larger boluses of filler. This may occur if the injector places higher amounts of pressure onto the syringe, especially when using a “sticky” syringe.[4] Lumps and nodules can be noticeable in superficial areas, as well as over bone with thin overlaying skin. They can be managed by using a firm massage to spread the HA or by injecting hyaluronidase in order to dissolve the HA.[1]

Tyndall Effect

Occasionally, HA filler can cause a bluish discoloration of the skin due to the Tyndall effect. The Tyndall effect states that blue light scatters to a larger degree than other colors of light with longer wavelengths when passing through small particles, such as HA. Thus, if too much HA is placed too superficially, a blue-grey discoloration can occur even without lumps.[4] Less viscous fillers are less likely to produce the Tyndall effect, possibly due to the more homogenous intradermal distribution of less viscous fillers.[5] For example, Belotero Balance has a low viscosity and is less likely to produce the Tyndall effect than more viscous formulations, such as Juvederm or Restylane products.[5][6] Some physicians dispute the theory that the Tyndall effect is what causes the bluish discoloration, positing that the color occurs because the HA filler displaces veins superficially, causing the skin to appear blue.[1] Regardless of why this occurs, management options include applying makeup, HA dissolution via hyaluronidase, and/or gentle massage.[1][4]

Malar Edema

HA fillers along the tear trough can cause malar edema in up to 11% of cases.[1] Anatomically, this occurs because of the malar septum. The malar septum is a fascial structure, which originates superiorly along the arcus marginalis of the orbital rim periosteum and inserts into the midcheek dermis inferiorly, with a lateral border of about 2.5–3 cm inferior to the lateral canthus[7] and a medial border near the nose. It divides the superficial orbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) into superficial and deep compartments.[8] The malar septum is a relatively impermeable barrier, allowing for tissue edema and hemoglobin accumulation above its cutaneous insertion.[7][8] Excessive volume or more elastic product in the superficial SOOF compartment can compress lymphatics and compromise drainage, leading to malar edema.[2][8][9]

Patients may present with malar edema years after treatment. This occurs because the HA can begin to absorb more water as it slowly de-polymerizes into smaller constituents.[1] Fillers to the tear trough are at higher risk for malar edema than other locations due to their proximity and superior location, where gravitational pull can result in malar edema.[9] Firmer gels, such as Perlane, Restylane, and Juvederm Voluma, have a higher elastic modulus and may be more likely to cause malar edema.[5][8][9][10]

The likelihood of malar edema can be reduced by limiting filler volume, selecting the proper filler, and placing filler material deep into the malar septum.[9] Bernardini et al. have found that management with hyaluronidase followed by repeat injection of an alternative HA filler 15days later can provide good results.[9]

Allergic Reactions

Allergic reactions to the HA injection are very rare, as HA is a natural constituent of skin. Injectable HA is derived from both avian and bacterial sources.[11] It is thought that residual proteins from the manufacturing process can cause hypersensitivity reactions.[11] Both immediate (type I) and delayed-type (type IV) hypersensitivity reactions are possible.

Immediate hypersensitivity reactions occur due to histamine release in response to antigen exposure. The histamine increases vascular permeability, resulting in edema, erythema, pain, and itching within minutes of the injection.[12] Treatment depends on the severity of the reaction. Many hypersensitivity reactions are mild and resolve spontaneously over hours to days. Oral antihistamines can be used to decrease swelling. Persistent edema refractory to antihistamines can be treated with oral steroids.[2]

Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions usually occur about 1–3 days after the treatment. These reactions are mediated by T cells, which are activated in response to an antigen. Signs and symptoms of DTH include erythema, edema, and induration, which usually resolve spontaneously without sequelae.[2] The treatment for persistent DTH reaction is oral steroids and hyaluronidase.[2][13] It is important to note that DTH reactions do not respond well to antihistamines.[13]

Infection

Although uncommon, infections secondary to HA fillers occasionally occur due to violation of the protective skin barrier, whether during injection or in the post-treatment period.[12][14][15]

Acute infections occur within two weeks of treatment and present with inflammation and/or abscess at the site of injection.[15] Rarely, multiple erythematous nodules may present, typically three to fourteen days after HA injection.[11][14] Systemic signs and symptoms, such as fever, chills, leukocytosis, and fatigue may or may not be present.[16] Typically, infection results from commensal skin flora, such as staphylococci and streptococci,[11][16] but viral and fungal infections can also occur.[11]

Delayed infections present similar to acute infections, but later at two or more weeks after the injection. These are highly suspicious for an atypical infection, especially with mycobacteria[16] or from herpes simplex virus[4] (HSV) (see below section, “Herpes Simplex Virus Reactivation”).

Empiric antibiotics are the best initial treatment for both acute and delayed bacterial infection.

The recommended initial antibiotics are amoxicillin-clavulanate or cephalexin (ciprofloxacin can be used if penicillin allergic).[2] In cases when etiology is uncertain, double coverage with both antibiotics and antivirals can be appropriate.[4] For an acute infection with a fluctuant abscess, incision and drainage, as well as culture and sensitivity, should be performed in addition to empiric antibiotics.[2] Once the infection is quiescent, hyaluronidase may be reconsidered.[2] In the presence of an active infection, hyaluronidase should only be used in combination with antibiotics to prevent spreading of the infected material.[2]

Herpes Simplex Virus Reactivation

Dermal fillers can lead to a reactivation of HSV. The majority of HSV recurrences occur in the nasal mucosa, perioral area, and hard palate mucosa.[13] In a patient with a history of cold sores, valacyclovir 1 gram daily can be considered the day preceding and continuing for three days following an injection,[13] as well as if an HSV episode occurs post-injection. In patients with active herpes lesions, HA fillers should be delayed until complete resolution.

Biofilms

Bacterial biofilms form a barrier that protects the bacteria from the immune system and antibiotics. Biofilms are omnipresent in the environment[17] and are the leading cause of device-associated infection in medical devices and implants.[18] HA fillers are a foreign material injected into the body and should thus be conceptually considered analogous to medical devices.[18] During the HA injection procedure, potential sources of biofilm inoculation include contamination from the local environment, needle, local skin flora, or HA itself.[17][18] Fastidious adherence to aseptic technique is essential to reduce the likelihood of bacterial biofilms.[17] Bacteria may remain dormant in the biofilm for long periods of time and reactivate when the local environment is more favorable.[4] This can result in granulomatous inflammation, nodules, abscesses, and full-blown recurrent infection.[4] The nodules are often culture negative and treatment can be complicated.8 Treatment is with oral ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin for 4-6 weeks.[8] The filler should be dissolved with hyaluronidase; occasionally surgical excision is required.[4][8]

Delayed-Onset Nodules

Delayed-onset nodules occur in 0.5% of HA filler treatments, typically four weeks to over one-year post-treatment.[15] These nodules are believed to occur due to either delayed onset inflammation or bacterial biofilms.[1][4][15] Often, they have preceding infectious or immune triggers.[1] One possible mechanism of action is through the breakdown of HA over time. On injection, HA has a high molecular weight, which provide anti-inflammatory properties. However, over time, this degrades into smaller fragments. These smaller fragments may be presented to the immune system and result in delayed-onset inflammation.[1] Another mechanism of action may be through the introduction of the skin flora with future aesthetic treatments, which then triggers inflammatory nodule formation.[15] Nodule culture is usually negative.[1] Management is with oral antibiotics, such as macrolides and tetracyclines. If symptoms are refractory to antibiotics, hyaluronidase can be added. Additional treatments can include a short course of systemic steroids, as well as intralesional steroids or 5-fluorouracil.[1]

Filler migration from distant sites can also cause delayed-onset nodules months to years after treatment.[1] However, these nodules are non-inflammatory.[1] These displaced filler nodules can be treated with hyaluronidase.[2]

Vascular Complications

Skin Necrosis

Skin necrosis as a result of HA fillers is a rare but calamitous complication. The incidence of ischemic complications related to HA fillers is about 0.3%.[1] Tissue necrosis is ideally prevented by having a thorough knowledge of facial vascular anatomy and meticulous technique, but anatomic variations occur and therefore necrosis can be a risk with even the most experienced injector.[19][20]

Necrosis occurs due to arterial or venous obstruction.[1][12] In HA fillers, the mechanisms of vascular interruption include accidental injection into an artery or vein, external compression of the vessel due to the filler, or direct trauma to the vessel wall.[1] Patients typically present clinically with severe prolonged pain and blanching. This is followed by livedo reticularis due to capillary obstruction, causing venule swelling, slow capillary refill, and dusky blue-red discoloration.[19] Late signs include necrotic areas, small white blisters, and tissue sloughing.[1][19] In cases of venous compression, symptoms may not initially be present as the clinical onset is generally slow and gradual;[12] symptoms may slowly occur over the course of many hours, with the longest reported interval between HA injection and onset of ischemic symptoms being 36 hours. In contrast, arterial embolic obstructions usually present with symptoms immediately post-injection.[21]

The mainstay of treatment is hyaluronidase, which should be on hand during an HA filler procedure.[19] Because hyaluronidase readily crosses fascial planes and blood vessel walls, gentle massage can be performed to aid in its distribution.[1][19] Warm compresses can help with vasodilation.[19] Other treatment options include aspirin, topical nitropaste, hyperbaric oxygen, and local injections of prostaglandin E1.[19]

Vision Loss

The most devastating vascular complications of HA filler injections are stroke and vision loss.[1][19] These occur due to arterial occlusion, when there is retrograde flow of the material into the arterial system. Retrograde passage of filler can occur because of Poiseuille’s law, which states that vessel branching and reduced diameter exponentially increases resistance to anterograde flow.[1] Additionally, pressure from the needle can promote retrograde flow.[12][19] Thus, injected filler may find lower resistance through retrograde flow to more proximal vessels.[1] It may then return to anterograde flow into vessels distant from the injection site, such as the ophthalmic artery.[19]

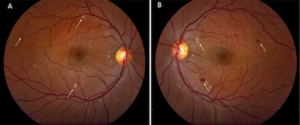

Fortunately, intracerebral stroke as an adverse event of HA fillers is exceedingly rare, with only a handful of occurrences reported in the scientific literature.[22] Similarly, vision loss from the use of HA fillers is also rare. Between 1906 and 2019, there were about 190 reported cases of blindness secondary due to injectable aesthetic treatments; however, most of these cases were due to autologous fat injections, resulting in retrograde emboli into the ophthalmic and central retinal arteries.[1] Hyaluronic acid–related embolic events occur in a similar manner, via retrograde flow. As HA is structurally much smaller than fat, it is more likely to move further into the vascular system and obstruct the smaller distal branches of the ophthalmic artery, such as the retinal and choroidal branches, as opposed to the larger ophthalmic or central retinal arteries.[1]

The periorbital area in particular is prone to vascular events due to its anatomy.[1] The external carotid artery supplies blood to most of the face, except for the eye, upper nose, and central forehead, which are supplied by the internal carotid artery. The ophthalmic artery possesses many branches that project to areas outside the ocular area into the nose and forehead. These branches anastomose with other arteries in the face, explaining why intravascular injections at sites distant from the eye can still result in visual loss (see figure of vision loss after injection to the gluteal area).[1] The injection sites with the highest risk for ocular complications are the glabella, nasal region, nasolabial fold, and forehead.[1][13][19]

Patients may present with a visual field defect and ocular pain.[19] Various measures to improve retinal perfusion have been described in the scientific literature, but unfortunately these have had limited success.[2] These measures include emergent ophthalmologic consultation, ocular massage, intraocular pressure–lowering eye drops, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, diuretics, systemic and topical corticosteroids, anticoagulation, and needle decompression of the anterior chamber.[2] The use of retrobulbar hyaluronidase in cases of vision loss is controversial, as it has not consistently proven to be effective. Recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that hyaluronidase cannot penetrate the optic nerve to reach the central retinal artery.[1] Retrobulbar injection could also result in additional complications, if done by an inexperienced provider.

Orbital Migration/Filler Migration

Orbital complications secondary to migrated filler may occur long after the initial procedure. Because of this and the fact that the site of the complication can be distant from the injection site, patients and physicians may not immediately recognize the connection, thus leading to delay in diagnosis.[23]

Conclusion

Hyaluronic acid fillers provide excellent results, are largely well tolerated, and have a favorable safety profile, but complications can occur. Fortunately, the incidence of adverse events is low and the vast majority are mild in nature. However, disastrous complications, such as skin necrosis, vision loss, and stroke, do occur very infrequently. Ultimately, complications are not completely avoidable for even the most skillful and experienced clinicians. Thus, awareness of the potential complications and their prevention and management, along with good knowledge of the underlying facial anatomy, are essential for safe patient care.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 Murthy R, Roos JCP, Goldberg RA. Periocular hyaluronic acid fillers: applications, implications, complications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30(5):395-400.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Signorini M, Liew S, Sundaram H, et al. Global aesthetics consensus: avoidance and management of complications from hyaluronic acid fillers—evidence- and opinion-based review and consensus recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(6):961e-971e.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Dayan SH. Complications from toxins and fillers in the dermatology clinic: recognition, prevention, and treatment. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21(4):663-673.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers, part I. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(4):561-575.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sundaram H, Fagien S. Cohesive polydensified matrix hyaluronic acid for fine lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5S):149S-163S.

- ↑ Gutowski K. Hyaluronic acid fillers: science and clinical uses. Clin Plast Surg. 2016;43(3):489-496.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Pessa JE, Garza JR. The malar septum: the anatomic basis of malar mounds and malar edema. Aesthet Surg J. 1997;17(1):11-17.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Funt DK. Avoiding malar edema during midface/cheek augmentation with dermal fillers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(12):32-36.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

- ↑ Kablik J, Monheit G, Yu L, et al. Comparative physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(s1):302-312.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Jones D, ed. Injectable Fillers: Principles and Practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Vidič M, Bartenjev I. An adverse reaction after hyaluronic acid filler application: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27(3):165-167.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado NE, Figueiredo V, et al. Treatment of soft tissue filler complications: expert consensus recommendations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(2):498-510.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Abduljabbar MH, Basendwh MA. Complications of hyaluronic acid fillers and their managements. J Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2016;20(2):100-106.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Heydenrych I, Kapoor KM, De Boulle K, et al. A 10-point plan for avoiding hyaluronic acid dermal filler-related complications during facial aesthetic procedures and algorithms for management. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:603-611.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Lowe NJ, Maxwell CA, Patnaik R. Adverse reactions to dermal fillers: review. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11 Pt 2):1616-1625.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Rohrich R, Monheit G, Nguyen A, et al. Soft-tissue filler complications: the important role of biofilms. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(4):1250-1256.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Saththianathan M, Johani K, Taylor. A, et al. The role of bacterial biofilm in adverse soft-tissue filler reactions: a combined laboratory and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(3):613-621.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers, part 2: vascular complications. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34(4):584-600.

- ↑ De Maio M, Swift A, Signorini M, et al. Facial assessment and injection guide for botulinum toxin and injectable hyaluronic acid fillers: focus on the upper face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(2):265e-276e.

- ↑ Souza Felix Bravo B, Klotz De Almeida Balassiano L, Roos Mariano Da Rocha C, et al. Delayed-type necrosis after soft-tissue augmentation with hyaluronic acid. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8(12):42-47.

- ↑ Lee S, Jung J, Seo J, et al. Ischemic stroke caused by a hyaluronic acid gel embolism treated with tissue plasminogen activator. J Neurocrit Care. 2017;10(2):132-135.

- ↑ Hamed-Azzam S, Burkat C, Mukari A, et al. Filler migration to the orbit. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(6):NP559-NP566.