Age-Related Macular Degeneration

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is an acquired degeneration of the retina that causes significant central visual impairment through a combination of nonneovascular (drusen and retinal pigment epithelium abnormalities), and neovascular derangement (choroidal neovascular membrane formation). Advanced disease may involve focal areas of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) loss, subretinal or sub-RPE hemorrhage or serous fluid, as well as subretinal fibrosis. A genetic underpinning is inferred from its predilection to those of European ancestry, although environmental, nutritional, and developmental (eg, aging) processes interact to affect the degeneration observed in the macula. Newly implicated biochemical pathways combined with a paucity of treatment options for most types of AMD (eg, dry AMD) has created fertile ground for novel therapeutics.

Disease Entity

International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

- ICD-9-CM

- 362.51 Nonexudative age-related macular degeneration

- 362.52 Exudative age-related macular degeneration

- ICD-10-CM

- H35.31 Nonexudative age-related macular degeneration

- H35.32 Exudative age-related macular degeneration

Disease

History

Drusen and disciform lesions have been observed in conjunction for well over 100 years.[1] The hallmark of age-related macular degeneration is the presence of drusen within the macula. The word druse (singular) is derived from the German word for node or geode.[2]

Key terms

- Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

- Nonexudative, dry, or nonneovascular AMD (synonyms)

- Exudative, wet, or neovascular AMD (synonyms)

- Geographic atrophy

- Choroidal neovascularization and choroidal neovascular membranes

Classification

- Early AMD: Defined by the presence of numerous small (<63 microns, “hard”) or intermediate (≥63 microns but <125 microns, “soft”) drusen. Note: Small drusen are frequently seen in those age 50 years and older, and can represent an epiphenomenon of aging (therefore, intermediate drusen are more specific for AMD).[3][4]

- Intermediate AMD: Macular disease characterized by either extensive drusen of small or intermediate size, or any drusen of large size (≥125 microns).[4] Note: 124 microns is the average diameter of the retinal vein at the optic disc margin.

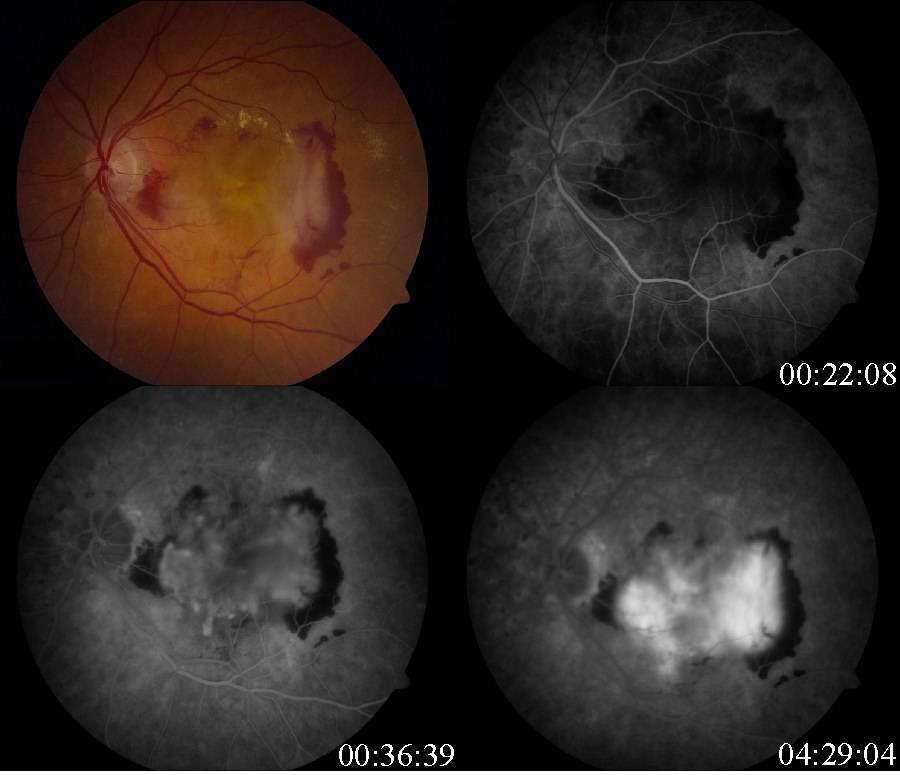

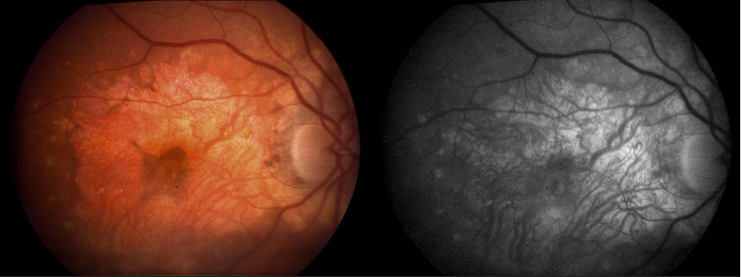

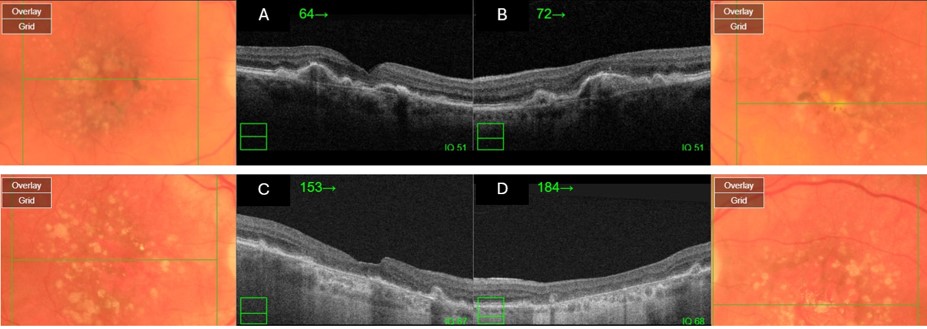

- Advanced AMD: Defined by the presence of either geographic atrophy or choroidal neovascular membrane (along with its sequelae, such as subretinal or sub-RPE hemorrhage or serous fluid, and subretinal fibrosis).[4] The figure below demonstrates progressive geographic atrophy over a 29-month period. There is also an area of choroidal neovascularization along the inferior aspect of the scar with subretinal fibrosis that progresses over these 29 months.

Macroeconomic disease burden

The costs of AMD to society and the patient have been divided into direct costs (direct ophthalmologic cost and direct non-ophthalmologic cost) and indirect costs.[5] Direct ophthalmologic costs include the cost of treatments (AREDS, intravitreal injections, laser treatment, diagnostic imaging, etc.). Direct non-ophthalmologic costs include special services and equipment such as rehabilitation services, low vision aids, and transportation services.[5] Measurement of these costs is more difficult and less pervasive in the literature. Indirect costs include lost productivity and workplace costs.[5] The annual loss of GDP due to neovascular AMD in 1 study was calculated to be $5.396 billion, and $24.395 billion for nonneovascular AMD.[6]

Etiology

A combination of risk factors interplays to modify the Bruch membrane/choroid complex, the retinal pigment epithelium, and photoreceptor cells. The initiating events affect one, both, or all of these tissue components. A change in one of these tissue components is thought to impart an influence on the others in such a way that an "intermediate disease mechanism” arises.[7] The degenerating retina succumbs to the final end point of geographic atrophy, choroidal neovascularization, and pigment epithelial detachment. Treatments targeting intermediate disease mechanisms or initiating disease factors are in the minority, but they may offer a more successful approach to vision preservation than those targeting relatively later steps in AMD pathophysiology (eg, choroidal neovascularization).[7]

Prevalence

The prevalence of advanced AMD in the Beaver Dam Eye Study was 1.6%, with the exudative form being present in 1 eye 1.2% of the time, and geographic atrophy in 1 eye 0.6% of the time.[3] The study involved 4,926 people between 43 and 86 years of age. Similar prevalence data was noted in the Framingham Eye Study, which reported a 1.5% prevalence of exudative AMD in those older than 52 years of age.[8] The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration sharply increases in those 75 years or older.[3]

Risk Factors

Age

AMD risk increases with age. The risk increases more than 3-fold in patients older than 75 years of age compared to the group of patients between 65 and 74 years of age (Beaver Dam Eye Study; Framingham Eye Study).[3][8]

Cigarette smoking

A ten pack-year tobacco smoking history is associated with increased development of exudative age-related macular degeneration.[9][10] After controlling for confounding factors such as socioeconomic status, alcohol consumption, and cardiovascular disease, the rates of visually significant AMD in smokers and nonsmokers over the age of 75 were calculated in a United Kingdom population-based cross sectional study.[11] Current smokers were twice as likely to have AMD-related vision loss when compared to nonsmokers, ex-smokers had a slightly increased risk (odds ratio of 1.13), and those who had stopped smoking over 20 years earlier were not at increased risk for developing vision loss from AMD.[11]

Genetic susceptibility

In addition to increasing one's risk of developing AMD, certain genetic loci have been associated with variable effects on treatment response, such as intravitreal anti-VEGF agents.[12]

Complement factor H (CFH) is an important gene in the pathogenesis of AMD.

Pharmacogenomic studies, such as these, may guide treatment regimens in the future, or may at least provide a more accurate prediction of treatment response. Recently, microRNA dysregulation has been linked with the development of AMD, modulation of which could provide potential treatments for the disease.[13]

Other risk factors

- cardiovascular disease

- hypertension

- female gender

- white race[14]

- hypercholesterolemia

- obesity

- hyperopia[15]

- family history

- light irides

General Pathology

Pathology vs. normal aging

Normal aging changes can be observed in the outer retina, RPE, Bruch membrane, and choriocapillaris, and many of these changes are difficult to separate from those seen in AMD.[16] In many instances, the designation of normal and abnormal has simply not been established to date. Furthermore, since aging is perhaps one of the most important risk factors for age-related macular degeneration, the physiological changes in aging may mirror the pathophysiological changes in age-related macular degeneration. Cumulative oxidative injury likely underlies changes seen in both aging and AMD, for example.[17] With age, within the outer retina, the photoreceptors become reduced in density. Within the RPE, melanin granules diminish, and lipofuscin granules form.[16][17] Sheet-like deposits called basal laminar deposits develop below the RPE but above the Bruch membrane (basal lamina of the RPE). Within the choriocapillaris, involutional changes are observed. Decreased choroidal blood flow, lumen diameter, and choriocapillaris number also occur with aging.[17] Scant, small, hard drusen alone cannot be pathognomonic for age-related macular degeneration, as focal deposition of acellular debris between the RPE and the Bruch membrane is found frequently in aged individuals, and is a normal finding in aging.[3][17][18] Age-related drusen, however, are biochemically distinct from drusen associated with AMD.[19] Large, confluent, or soft drusen are more likely to be a marker of age-related macular degeneration than normal aging.[20]

- Basal laminar deposits: Between RPE and the basement membrane of the RPE. Consist of "granular lipid-rich material and widely spaced collagen fibers."

- Basal linear deposits: Within the inner aspect of the Bruch membrane. Consists of "phospholipid vesicles and electron-dense granules."

Drusen

Drusen consist of extracellular deposits rich in lipids, proteins, and inflammatory components and are considered the hallmark of AMD.[21] On histopathology, nodular drusen appear as eosinophilic dome-shaped structures situated between the Bruch membrane and the displaced, attenuated RPE overlying the drusen. Drusen display dense PAS-positivity. They may become more basophilic with accumulation of calcium. Von Kossa staining may reveal calcific granules or calcific stippling within such calcified drusen. Soft or large drusen may occur with the development of localized detachments of basal laminar or basal linear deposits, which represent granular material accumulating between either the RPE and its basement membrane or external to the RPE's basement membrane, respectively.[22] The size and density of drusen are determinant factors in the progression of the disease.[23]

Drusen ooze

The term "drusen ooze" describes the seepage of drusenoid material from the RPE into the outer retinal layers due to RPE dysfunction or collapse.[24] This seepage material appears hyperreflective on OCT and may be associated with RPE thinning, PED collapse, or ellipsoid zone disruption. Drusen ooze is considered a structural biomarker in intermediate to advanced nonexudative AMD, and it has been reported to have a prevalence of 41%-65% in patients with dry AMD.[25][26]

Three imaging patterns of drusen ooze have been described, helping to distinguish this finding from other hyperreflective abnormalities on OCT:

- Increased RPE reflectivity above a druse, appearing brighter than the adjacent, normally apposed RPE overlying the Bruch membrane.

- Discrete hyperreflective foci at the RPE level (hyperreflective dots, HRDs), visually similar in brightness to the elevated RPE but not physically continuous with the RPE layer.

- Intermediate-reflectivity dots within the outer nuclear or plexiform layers that are more reflective than the surrounding retina but less so than the hyperreflective foci. These are typically associated with localized disruptions in the RPE.[26]

Oozing may occur subtly, as a slow leak, or more dramatically as a “volcano-like” eruption from within the druse. The term “vent” has been used to describe hyperreflective foci migrating through the Henle fiber layer. corresponding histologically to migrating RPE cells and RPE debris. The features of drusen ooze are important to recognize, as misclassification as CNV may lead to overtreatment with anti-VEGF injections.

Drusen ooze has been suggested to be a biomarker indicative of AMD progression. Monés and colleagues (2017) evaluated 48 eyes of 33 patients with AMD and soft drusen, finding collapse of 1 or more drusen occurring in 39.6% over ≥18 month follow-up. Of the foci of collapsed drusen examined, 91.2% were associated with RPE hyperreflectivity, 32.2% with RPE defects and isoreflective dots on OCT, and 79.4% with HRDs overlying the RPE, all features of drusen ooze.[24] The authors hypothesized that drusen ooze activates the phagocytic/endocytic activity of RPE cells, eventually overwhelming RPE capacity and resulting in RPE death/atrophy. Jhingan and colleagues (2021) evaluated 72 eyes with intermediate dry AMD, finding 20.3 times greater odds of progression to incomplete or complete RPE and outer retinal atrophy in eyes with drusen ooze at baseline compared to eyes without this feature. Notably, this group did not find a correlation between drusen ooze and conversion to exudative AMD.[26]

Serous detachments of the RPE

On histopathology, serous RPE detachments can be associated with thickening of the inner aspect of the Bruch membrane.[22]

RPE atrophy

Histopathologically, RPE atrophy may be associated with depigmentation, migration, and proliferation of RPE cells into the photoreceptor layer. With progression, RPE degeneration is seen, with loss of adjacent photoreceptors, and juxtaposition of the Bruch membrane to the inner nuclear layer.[22]

Subretinal or sub-RPE neovascularization

Sub-RPE neovascularization is located within the Bruch membrane, typically between the thickened inner aspect of the Bruch membrane and the rest of the Bruch membrane. A sub-RPE neovascular membrane can extend subretinally in areas where the Bruch membrane is not intact. With discontinuities in the Bruch membrane, capillary-like choroidal vessels can form a subretinal RPE vascular web that can affect serous or hemorrhagic detachments of the neurosensory retina.[22]

Disciform scars or lesions

Fibrous disciform scars are usually results of sub-RPE neovascularization. Fibrous tissue develops within the Bruch membrane or between the RPE and retina. Hemosiderin is typically present, suggesting a hemorrhagic antecedent event. RPE hyperplasia may be a prominent feature of disciform scarring, and lymphocytic infiltrate in the adjacent choroid is occasionally appreciated. Overlying retina undergoes cystic degeneration with photoreceptor loss.[22]

Pathophysiology

Genetic and biochemical pathways in AMD (see [27])

Biochemical pathways and genetic association studies have shed light on the possible biochemical pathways that go awry in AMD. Two polymorphisms, Tyr402His at 10q26 (Complement factor H locus), and Ala69Ser (LOC387715) may be responsible for up to 50%-75% of the genetic risk of AMD.[28] One caveat of these risk alleles is that they have not been validated in racial groups other than whites. Aside from explaining some of the genetic predisposition in AMD, these loci have uncovered new biochemical pathways hitherto unlinked to AMD pathogenesis, providing novel therapeutic targets. Pathway-based treatment modalities targeting oxidative damage, lipofuscin accumulation, inflammation, and derangements in complement activation are rapidly proliferating.[29] The following list represents the biochemical pathways implicated in AMD pathogenesis and the corresponding genetic loci involved.

- Complement pathway (complement factor 2,[30] complement factor 3,[31] complement factor B,[32] complement factor H, complement factor I)[33][34][35][36][37]

- Extracellular matrix function, cellular anchoring (Fibulin 5[38] and 6[39][40])

- Innate immunity (Toll-like receptor 3 and 4)[41][42][43][44][45]

- Proteolysis/Drusen metabolism (HTRA1, serine protease)[46][47]

- DNA repair (ERCC6)[48]

- DNA transcription (RAX2)[49]

- Lipid signaling/metabolism (transporter protein, ABCA4)[50][51][52][53]

- Other (LOC387715, hypothetical gene)[54][55]

The complement system

The complement system is a three-pronged pathway involved in natural and acquired immunity. It represents a highly regulated conglomeration of approximately 30 proteins, some of which are cell surface receptors, while others possess catalytic activity. The 3 prongs of the pathway include the classical, the alternative, and the lectin pathways. The classical pathway depends on activation by antigen-antibody complexes, the lectin pathway, on carbohydrate residues, and the alternative pathway depends on spontaneous activation. Complement activity may increase in response to surface features on microorganisms. Components in cigarette smoke may also trigger this activity.

Activation of the complement system results in cellular damage that is central in the pathogenesis of dry and wet forms of AMD, and this is supported by the presence of many complement system proteins within drusen in patients with AMD. The alternative pathway becomes activated through a process known as "tickover.. Under normal circumstances, proteins expressed on host cells inhibit this tickover process, and in so doing prevent injury to the host. Instances in which this inhibition is jeopardized include when factors favoring activation increase locally (or systemically), when inhibitors decrease (or their function decreases), or when there is an increase in local concentration of alternative pathway components.[56] Therefore, there needs to be active, continuous control over the alternative pathway to avoid autologous tissue destruction.

In AMD, it is believed that an early "seeding event," such as an area of retinal pigment epithelium atrophy with cellular debris, induces innate immune system activation at the RPE-choroid-the Bruch membrane complex.[57] Subsequently, complement attack (membrane attack complex activation) leads to collateral damage of retinal tissue. This damage predisposes to geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascular membrane formation. In 2005, 4 groups independently reported that a polymorphism at amino acid position 402 of factor H is associated with AMD.[58][59][60][61] Factor H is the main soluble inhibitor of the alternative complement pathway. Mutation in factor H in the same region where the polymorphism is encountered has been associated with type II membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, a condition wherein drusen also develop.[56][62]

Primary Prevention

Smoking cessation, reduction in body mass index, and treatment of hypertension are modifiable risk factors that should be addressed in patients at risk for, or who have various stages of AMD.[4] Based on population based cross sectional studies, the prevalence of AMD in ex-smokers is less than in smokers, arguing for a possible benefit of smoking cessation on societal AMD disease burden.[11] Studies on the beneficial effect of dietary antioxidants and omega 3 fatty acids on prevention of AMD have yielded insufficient results.[63][64]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of early AMD is typically made after considering a patient's age, physical exam findings, and family history, as many patients in early stages of the disease possess no symptoms.

History

Decreased central visual acuity may not be present in AMD, especially in early stages, and is not a reliable indicator of disease severity. In fact, advanced AMD may be associated with relatively preserved visual acuity (see time lapse fundus photograph above, where a patient had 20/40 vision despite advanced AMD). Exudative AMD changes may be associated with acute to subacute drops in vision, or perception of visual distortion, such as metamorphopsia.

Physical examination

- Periodic dilated fundus exams are warranted to identify patients who progress to neovascular AMD without having symptoms.

- Amsler grid

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Amslergrid_patientAMD.gif

- The Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter (PreView PHP, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA/ ForeseeHome) is useful, when available, to identify new-onset neovascular AMD changes.[65]

Signs

- Drusen

- Geographic atrophy

- Subretinal fibrosis

- RPE changes

- Subretinal fluid or hemorrhage/hard exudate

Symptoms [65]

- Decreased visual acuity, insidious or sudden-onset

- Dry AMD constitutes 85%-90% cases of AMD, and usually does not cause severe vision loss.

- Wet AMD constitutes 10%-15% of AMD cases and is the major cause of severe vision loss.

- Blurred vision

- Distorted near vision

- Scotoma

- Visual distortion, metamorphopsia, micropsia

- Vague visual complaints

Clinical diagnosis

The hallmark findings in nonexudative AMD are drusen, RPE changes, and geographic atrophy. In advanced AMD, drusen may fade or become resorbed in areas of geographic atrophy. Large areas of geographic atrophy may show prominent deep choroidal vessels with atrophy of the choriocapillaris.

Diagnostic procedures

Fundus fluorescein angiography/FFA

Fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography are useful in evaluating for the presence of exudative AMD. Fluorescein angiography is performed when there is suspicion for choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) formation. AMD pathology on fluorescein angiography can be organized into hyperfluorescent changes and hypofluorescent changes. Changes in AMD that cause hypofluorescent changes are few, and include hemorrhage, lipid exudation, and pigment hyperplasia. Causes of hyperfluorescent lesions are more numerous and include drusen, RPE atrophy (transmission defects), choroidal neovascular membranes, serous pigment epithelial detachments, and subretinal fibrosis or scars (staining defects).[66] Choroidal neovascular membranes can present differently on angiography. Two main designations are "classic"vs. "occult." Fluorescein angiographic features help distinguish classic choroidal neovascularization and occult choroidal neovascularization. Differences in angiographic patterns are thought to arise from "classic" lesions penetrating the retinal pigment epithelium, and thus being located in front of the RPE, and "occult" lesions being sub-RPE.[67] Classic membranes are associated with an early hyperfluorescent area that is well-demarcated, which increases in intensity and extent beyond the early phase boundary by mid- to late-frames. Pooling of fluorescein associated with a concomitant subsensory retinal detachment may also be appreciated.

Occult membranes are presumed when late choroidal leakage is noted without a discernible classic membrane pattern. Occult membranes are also presumed when a fibrovascular pigment epithelial detachment (FVPED) is suspected. FVPEDs are associated with irregular RPE elevation, and a stippled hyperfluorescent pattern with or without leakage or pooling.[65]

Types of CNVM on FFA

- Classic CNVM: an area of discrete well-defined bright, fairly uniform lacy hyperfluorescence in the early phase (usually near the subretinal bleed) that progressively increases in intensity and size with blurring of the margin of hyperfluorescence (leak)

- Occult CNVM

- a. Fibrovascular pigment epithelial detachment: Better appreciated with stereoscopic views. At 1-2 minutes, there is an irregular elevation of the RPE with stippled or granular hyperfluorescence. As time passes, the boundary may or may not show leakage. The margin of FVPED may be apparent in around 1-2 minutes of the FFA, or the margin may be difficult to ascertain in some cases.

- Late leakage of an undetermined source: In early or mid phase, there is no well-defined area of hyperfluorescence like what is seen with classic CNVM or FVPED. The leakage is usually deep/choroidal or at the RPE and late, associated with speckled appearance and pooling of dye in the subretinal space overlying the speckles.

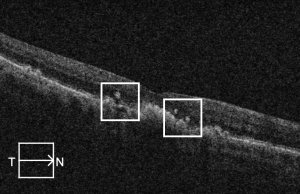

Optical coherence tomography/OCT

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) offers a noninvasive, high-resolution, optical cross-sectional method that utilized low-coherence interferometry.[68] OCT has become indispensable in the evaluation of patients with AMD. Imaging helps evaluate for tomographic sequelae of neovascular membranes, as well as monitor for treatment responses.

Type 1 CNVM= sub-RPE CNVM, usually related to occult CNVM on FFA

Type 2 CNVM= subretinal CNVM (superficial to the RPE), usually corresponds to classic membranes on FFA

Type 3 CNVM= retinal angiomatous proliferation (RAP)

Laboratory tests

No routine blood tests are available to diagnose AMD, and although elevated inflammatory markers (eg, CRP) and certain genetic polymorphisms have been associated with increased risk of developing advanced AMD, these tests are not routinely employed.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of age-related macular degeneration varies greatly, depending on whether choroidal neovascularization is present or not, so it is useful to organize the differential into "nonexudative" vs. "exudative" AMD.

- Exudative AMD. The differential diagnosis of neovascular AMD includes choroidal neovascularization caused by conditions other than AMD, such as ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, pathologic myopia, choroidal rupture, angioid streaks, or idiopathic causes.[65] In addition, foveal detachments or vitelliform detachments may complicate other conditions, such as cuticular drusen, or pattern dystrophies. The latter would not be associated with leakage on fluorescein angiography, but rather progressive staining of vitelliform material.[65] Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy may produce hemorrhagic PEDs that can resemble those in AMD, but the absence of drusen, the often peripapillary location of such lesions, and the better visual acuity outcomes of polypoidal vasculopathy help distinguish it from AMD.[69] Choroidal tumors obscured by subretinal hemorrhage or RPE changes may also masquerade for exudative AMD, but unilaterality and ultrasonography should help distinguish a tumor from AMD.[65] Central serous retinopathy is an important differential, especially of occult CNVM.

- Nonexudative AMD: The differential diagnosis of nonneovascular AMD includes retinal pigment epithelial changes secondary to central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC), pattern dystrophy, cuticular drusen, and drug toxicity (eg, chloroquine toxicity). These conditions overlap with the various pathological changes observed in dry AMD, but either occur in a younger patient population, or are missing key AMD features, such as drusen. For example, CSC may present with multiple serous PEDs and RPE changes, but not drusen. Pattern dystrophy usually affects patients younger in age than AMD does, and it has a fluorescein angiography pattern that is distinct, with early blocked fluorescence with surrounding hyperfluorescence, and late staining of the vitelliform material.

Management

Observation with risk factor modification and nutritional supplementation is the mainstay of treatment for nonexudative AMD. However, current studies are under way to evaluate complement pathway inhibition for the treatment of geographic atrophy in patients with nonexudative AMD, although no treatment modality is currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of geographic atrophy. Exudative AMD is managed with more closely spaced examinations and intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents or laser treatments. Patients with advanced disease in both eyes should undergo evaluation and rehabilitation with low-vision services.[70]

Medical therapy

Non-neovascular AMD treatments

Antioxidant and mineral supplementation

Antioxidant and mineral supplementation has been shown to reduce the risk of progression in AMD.[71] The daily amounts of antioxidants and zinc in the AREDS formulation is :[4][72]

- 500 milligrams of vitamin C

- 400 International Units of vitamin E

- 15 milligrams of beta-carotene (equivalent of 25,000 International Units of vitamin A)

- 80 milligrams of zinc as zinc oxide

- 2 milligrams of copper as cupric oxide

Since, high-dose zinc supplementation can lead to a copper-deficiency anemia by inhibiting copper absorption at the level of the enterocyte, copper supplementation was added to the AREDS formula.[4] Cigarette smokers should be warned about the small, but real, potential risk of lung cancer with high dose beta-carotene supplementation in the AREDS formula. Non-beta-carotene-containing supplements are more appropriate for this subgroup of patients.[70]

Based on data suggesting that increasing intake of lutein + zeaxanthin, and omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (docosahexaenoic acid [DHA] + eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA]) might reduce the risk of developing advanced AMD, AREDS2, a randomized, double-masked control trial was started. AREDS2 was designed to test whether adding lutein + zeaxanthin, DHA + EPA, or lutein + zeaxanthin + DHA + EPA to the AREDS formulation further reduces the risk of progression to advanced AMD. Another goal of AREDS was to test the effects of eliminating beta carotene and reducing the zinc dose from the AREDS formulation. The following are the modifications of AREDS2:

- 10 mg lutein and 2 mg zeaxanthin

- 350 mg DHA and 650 mg EPA

- No beta-carotene

- 25 mg zinc

In AREDS2, lutein/zeaxanthin or DHA/EPA had no additional effect on the risk of advanced AMD. Study participants who took AREDS containing lutein/zeaxanthin and no beta-carotene had a slight reduction in the risk of advanced AMD, compared to those who took AREDS with beta-carotene and no lutein/zeaxanthin. Importantly, former smokers who took AREDS with beta-carotene had a higher incidence of lung cancer. Lower zinc oxide doses (25 mg) did not significantly increase the risk of advanced AMD, although a trend to more protection from advanced AMD was noted with higher zinc oxide doses (80 mg). Newer formulations replace beta-carotene with lutein/zeaxanthin, but keep the zinc oxide dose the same.

- 500 milligrams of vitamin C

- 400 International Units of vitamin E

- 80 milligrams of zinc as zinc oxide

- 2 milligrams of copper as cupric oxide

- 10 mg lutein and 2 mg zeaxanthin

- No beta-carotene

Complement factor inhibitors

The complement factor 3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan has been assessed for the treatment of the geographic atrophy (GA) in the phase 3 DERBY and OAKS trials. In the DERBY trial, monthly dosing of pegcetacoplan led to a 36% decrease in lesion growth, while every other month dosing of pegcetacoplan led to a 29% decrease in lesion growth at 24 months. The OAKS trial showed a 24% decrease in GA growth with every-month dosing, and a 25% decrease in lesion growth with every-other-month dosing. No clinically meaningful differences were noted on functional outcomes. In terms of adverse events in DERBY and OAKS, the monthly pegcetacoplan had a 12% rate of choroidal neovascularization (CNV). 3.8% risk of intraocular inflammation (IOI), and 1.7% rate of ischemic optic neuropathy, while the every other month dose had a 7% rate of CNV. 2.1% rate of IOI, and 0.2% of optic neuropathy, compared to a 3% risk of CNV, 0.2% risk of IOI, and 0% risk of optic neuropathy in the sham. Pegcetacoplan was approved for the treatment of GA by the FDA on February 17, 2023.

The complement factor 5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol has also been assessed for the treatment of geographic atrophy in the phase 2/3 GATHER1 and phase 3 GATHER2 trials. GATHER1 evaluated multiple doses of avacincaptad, the first part looked at 1 mg and 2 mg monthly versus sham in 1:1:1 ratio, the second part compared 2 mg and 4 mg monthly versus sham in a 1:1:1 ratio. GATHER2 evaluated 2 mg avacincaptad monthly versus sham in a 1:1 ratio, again with primary endpoint of mean rate of growth of GA at 12 months and with secondary endpoints at 18 months related to GA growth and visual function. The inclusion criteria are notable for requiring nonsubfoveal GA; thus, these patients did not have subfoveal GA, in contrast to the OAKS and DERBY trials. At 12 months, GATHER1 showed a 35% decrease in GA growth, while GATHER 2 showed a 17.7% decrease in GA growth. No statistically significant effects were found in BCVA between treated and SHAM groups. The 2mg dose of avacincaptad in GATHER1 had a 9% risk of CNV, 1.5% of IOI, and no instance of optic neuropathy, compared to a 2.7% risk of CNV in the sham. In GATHER2, there was a 6.7% risk of CNV vs a 4.1% risk in sham, and no instances of IOI or optic neuropathy. Avacincaptad pegol was approved for the treatment of GA by the FDA on August 6, 2023.

Neovascular AMD treatments

Macular photocoagulation studies

Studies performed in the 1980s assessed the efficacy of laser photocoagulation in limiting damage caused by choroidal neovacular lesions. These studies evaluated laser treatment of extrafoveal, juxtafoveal, and subfoveal neovascular membranes.[73][74] Patients with direct laser photocoagulation to extrafoveal or juxtafoveal sites fared better than those receiving direct laser to subfoveal membranes. While severe vision loss was averted, laser photocoagulation currently has limited utility because of its high recurrence rates, risk of inducing vision loss (especially with subfoveal membranes), and failure to effect an improvement in vision from baseline visual acuity. In the era of anti-VEGF therapies, the indications for direct photocoagulation are diminishing.

However, it may be considered in extrafoveal small CNVM.

Verteporfin photodynamic therapy/vPDT

Use of photosensitizers (eg, verteporfin) that pool in neovascular membranes and subsequently produce reactive oxygen species upon activation with light of a specific wavelength was introduced in the late 1990s. In the era of anti-VEGF therapies, the indications for photodynamic therapy are diminishing.

However, PDT has a definite role in the management of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and central serous chorioretinopathy. The EVEREST trial showed that "after 12 months, combination therapy of ranibizumab plus vPDT was not only noninferior but also superior to ranibizumab monotherapy in best-corrected visual acuity and superior in complete polyp regression while requiring fewer injections."

Anti-VEGF treatments

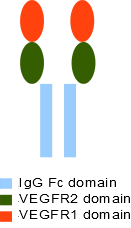

Optical coherence tomography and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy together have revolutionized the treatment of exudative AMD. Ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech, San Francisco, CA), bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech, San Francisco, CA), and aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tarrytown, NY), are frequently used in the treatment of exudative AMD. Pegaptanib (Macugen, Pfizer) was the first anti-VEGF therapy to receive FDA approval for the treatment of AMD in 2004. It is biochemically distinct from subsequent anti-VEGF agents, in that it represents an aptamer as opposed to a monoclonal antibody (bevacizumab), monoclonal antibody fragment (ranabizumab), or a receptor-antibody fusion protein (aflibercept, see diagram below). Pegaptanib is a small oligonucleic acid molecule that binds specifically to the VEGF-165 isoform. The most recent anti-VEGF agent that was recently approved was brolucizumab (Beovu, Novartis, Cambridge, MA), which is a single-chain antibody fragment against VEGF, which was found to be noninferior to aflibercept, and more than half of patients were able to extend to 3 months' dosing with brolucizumab within the first year, as demonstrated in the HAWK and HARRIER trials.

In an effort to extend dosing, a new port delivery system was developed by Genentech to deliver continuous levels of ranibizumab. The ranibizumab port delivery system (Susvimo, Genentech, San Francisco, CA) is a unique surgical implant that is placed within the vitreous and provides continuous delivery of ranibizumab. This implant was approved by the FDA in October 2021, and this delivery system can be refilled every 6 months. The Archway study showed noninferiority of the port delivery system, compared to monthly ranibizumab injections; 98% of patients were able to go 6 months before their first refill.

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy has been used in neovascular AMD under the premise that radiation can inhibit the exuberant cellular proliferation necessary to create the choroidal neovascular membrane. However, studies on efficacy have not shown a clear benefit of this treatment modality.[65]

Anti-VEGF and Anti-Ang2 treatment

The first bispecific antibody therapy for the treatment of neovascular AMD was approved by the FDA on January 31, 2022. Faricimab (Vabysmo, Genentech, San Francisco, CA) is a bispecific antibody directed against both VEGF and angiopoietin-2. This dual targeted treatment was dosed up to 4 month intervals and was found to be noninferior to aflibercept given every 2 months in the first year. In the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials, a large majority of patients could be dosed at 3-month intervals or more, showing improved efficacy and durability of the treatment compared to the anti-VEGF inhibition alone.

Emerging treatments

Treatments targeting biochemical pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of AMD are being tested actively in clinical trials.[75][29] Agents currently undergoing evaluation in geographic atrophy /advanced AMD are listed in the table below. Treatments include small inhibitory RNA molecules, monoclonal antibodies, gene therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, antioxidants, and cell-based therapies.

Information for the following table was retrieved from http://clinicaltrials.gov on 2/2024.[76]

| Investigational agent | Route of administration | Mechanism of action | Targeted Pathology | Clinical Trial Identification | Sponsoring company/institution | Study status | Phase of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iptacopan | Oral | Inhibitor of Complement Factor B | Geographic atrophy | NCT05230537 | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | Recruiting | 2 |

| CT1812 | Oral | Sigma-2 receptor modulator | Geographic atrophy | NCT05893537 | Cognition Therapeutics | Recruiting | 2 |

| OTX-TKI | Intravitreal | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Neovascular AMD | NCT06223958 | Ocular Therapeutix, Inc | Recruiting | 3 |

| AXT107 | Suprachoroidal | Integrin modulator | Neovascular AMD | NCT05859776 | AsclepiX Therapeutics, Inc. | Recruiting | 1, 2 |

| ADVM-022 | Intravitreal | Gene therapy based expression of anti-VEGF agent aflibercept | Neovascular AMD | NCT03748784 | Adverum Biotechnologies, Inc. | Completed | 1 |

| RPESC-RPE-4W | Subretinal | Allogeneic RPE stem cell-derived RPE cells | Non-neovascualar AMD | NCT04627428 | Luxa Biotechnology, LLC | Recruiting | 1, 2 |

| RGX-314 | Intravitreal | Gene therapy based expression of anti-VEGF | Neovascular AMD | NCT04514653 | AbbVie | Recruiting | 2 |

| OPT-302 | Intravitreal | VEGF-C, VEGF-D inhibition | Neovascular AMD | NCT04757636 | Opthea Limited | Recruiting | 3 |

| 4D-150 | Intravitreal | Gene therapy delivery of aflibercept and RNAi against VEGF-C | Neovascular AMD | NCT05197270 | 4D Molecular Therapeutics | Recruiting | 1, 2 |

| AR-14034 | Intravitreal | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Neovascular AMD | NCT05769153 | Aerie Pharmaceuticals | Recruiting | 1, 2 |

| AVD-104 | Intravitreal | Sialic acid–coated nanoparticle | Neovascular AMD | NCT05839041 | Aviceda Therapeutics, Inc. | Recruiting | 2 |

Surgery

Submacular surgery in AMD has included approaches to translocate the macula, either by vitrectomy and retinotomy or by vitrectomy and sclerochoroidal foreshortening (achieved externally), yet these procedures have not gained widespread use.[65] In instances where a large submacular hemorrhage occurs, pneumatic displacement with face-down posititioning and intraocular gas injection can be performed. Some have used vitrectomy, retinotomy, and subretinal injection of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in instances of large submacular hemorrhage. The NEI-funded Submacular Surgery Trials (SST) evaluated the visual acuity outcome and complications of excising choroidal neovascular membranes. In patients with large central macular, subretinal hemorrhage due to choroidal neovascularization (new or recurring after laser photocoagulation; Group B protocol), there were no significant differences in BCVA between the surgery and observation arms of the study. The surgical intervention can vary from patient to patient, but it has the goal of removing the entire neovascular membrane, any blood, and any scar tissue present.[77]

Complications

Subretinal hemorrhage

Subretinal hemorrhage can cause photoreceptor damage as the blood is in contact with the photoreceptors and early treatment is needed. Subretinal hemorrhage may be of varying severity. Massive subretinal hemorrhages are typically thought to be associated with anticoagulation therapy, specifically, warfarin therapy.[65] Surgical management options have been reviewed elsewhere (Management of Submacular Hemorrhage).

Vitreous hemorrhage

Breakthrough vitreous hemorrhage secondary to neovascular AMD is a rare complication. Sudden peripheral visual field and central vision loss is noted in these instances, to be distinguished from the central field complaints typically noted with AMD. Other etiologies, such as retinal tears from hemorrhagic posterior vitreous detachments, retinal vascular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, or vein occlusions should be considered as well.[65]

Diplopia

Diplopia can occur as a result of the choroidal neovascular membrane "dragging" the fovea. Such patients present with central binocular diplopia in the presence of peripheral fusion. This syndrome is referred to as dragged-fovea diplopia syndrome, and it is usually addressed with some form of partial monocular occlusion (Scotch Satin tape).[78]

Legal blindness

Severe central vision loss leading to legal blindness (visual acuity less than 20/200) is an endpoint more frequently seen in neovascular AMD compared to nonneovascular AMD. Based on data from the Framingham Eye Study[8] and a case-control study by Hyman and colleagues,.[79] the proportions of neovascular and nonneovascular AMD in patients legally blind in an eye from advanced AMD were compared;[80] 79% to 90% of legal blindness in advanced AMD was associated with neovascular, and not nonneovascular disease.[80]

Additional Resources

- Boyd K, Gregori NZ, Turbert D. Age-Related Macular Degeneration. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/age-related-macular-degeneration-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Porter D, Vemulakonda GA. Drusen. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/drusen-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Turbert D, Vemulakonda GA. Avastin. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/drugs/avastin-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Turbert D, Vemulakonda GA. Lucentis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/drugs/lucentis-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Turbert D, Vemulakonda GA. Eylea. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/drugs/eylea-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Turbert D, Vemulakonda GA. Anti-VEGF Treatments. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/drugs/anti-vegf-treatments-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Clinicaltrial.gov-U.S. National Institutes of Health

- Retinal information network

- Webvision

- The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Research Group. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2005-2015. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.4997.

References

- ↑ Hutchinson J, Tay W. Symmetrical central choroido-retinal disease occurring in senile persons. Roy Lond Ophthalmol Hosp Rep. 2009. 1875; 83:275.

- ↑ German dictionary. Accessed 6/2012 @ http://dict.tu-chemnitz.de/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Klein R, Klein BEK, Linton KLP (1992). Prevalence of age-related maculopathy-The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992. 99(6):933-943.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Coleman HR, Chan CC, Ferris FL III, Chew EY. Age-related macular degeneration. 2008. Lancet. 372(9652):1835-1845.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Gupta OP, Brown GC, Brown MM. Age-related macular degeneration: the costs to society and the patient. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007. 18:201-205.

- ↑ Brown MM, Brown GC, Stein JD, et al. Age-related macular degeneration: economic burden and value-based medicine analysis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005. 40:277-287.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bird AC. Therapeutic targets in age-related macular disease. J Clin Invest. 2010. 120(9):3033-3041.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Leibowitz Hm, Krueger DE, Maunder LR, et al. The Framingham Eye Study Monograph. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980. 24:335-610.

- ↑ Clemons TE, Milton RC, Klein R, Sedon JM, Ferris FL III. Risk factors for the incidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): AREDS report no. 19. Ophthalmology. 2005. 112:533-539.

- ↑ Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H, Clayton DG, Yates JRW, Bradley M, Moore AT, Bird AC. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: the number of pack years of cigarette smoking is a major determinant of risk for both geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006. 90:75-80.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RPL. 28,000 Cases of age related macular degeneration causing visual loss in people aged 75 years and above in the United Kingdom may be attributable to smoking. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005. 89:550-553.

- ↑ Smailhodzic D, Muether PS, Chen J, Kwestro A, Zhang AY, Omar A, Van de Ven JP, Keunen JE, Kirchhof B, Hoyng CB, Klevering BJ, Koenekoop RK, Fauser S, den Hollander AI. Cumulative effect of risk alleles in CFH, ARMS2, and VEGFA on the response to ranibizumab treatment in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012 Nov;119(11):2304-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.040. Epub 2012 Jul 26. PMID: 22840423.

- ↑ Berber, P., Grassmann, F., Kiel, C. and Weber, B.H., 2016. An Eye on Age-Related Macular Degeneration: The Role of MicroRNAs in Disease Pathology. Mol Diagn Ther. 2017.1-13.

- ↑ Friedman, D. S., Katz, J., Bressler, N. M., Rahmani, B., & Tielsch, J. M. (1999). Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration: The Baltimore eye survey. Ophthalmology, 106(6), 1049-1055.

- ↑ Sandberg MA, Tolentino Mj, Miller S, Berson El, Gaudio AR. (1993) Hyperopia and neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 100: 1009-113.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Guymer R, Bird AC. Chapter 59. Age Changes in Bruch's Membrane and Related Structures. Retina, 4th Ed (2006). Volume II Schahcat AP, Ryan SJ. Elsevier Mosby.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Zarbin MA 2004. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmology. 122:598-614.

- ↑ Jager RD, Mieler WF, Miller JW (2008). Age-Related Macular Degeneration. N Engl J Med. 358;24: 2606-2617.

- ↑ Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, et al. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99:3842-3847.

- ↑ Bressler NM, Bressler SB, West SK, Fine SL, Taylor HR. The grading and prevalence of macular degeneration in Chesapeake Bay watermen. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989. 107: 847-852.

- ↑ Zhang X, Sivaprasad S. Drusen and pachydrusen: the definition, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Eye (Lond). 2021; 35:121-133.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Green W.R. 1996. Ophthalmic Pathology:An Atlas and Textbook, Volume 2, Chapter 9. Retina, pp 982-1047 W.B. Saunders Company.

- ↑ Davis MD, Gangnon RE,Lee L-Y, Hubbard LD, Klein BEK, Klein R et al. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 17. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123(11):1484–1498.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Monés J, Garcia M, Biarnes M, Lakkaraju A, Ferraro L. Drusen ooze: a novel hypothesis in geographic atrophy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017; 1(6):461-473.

- ↑ Schuman SG, Koreishi AF, Farsiu S, et al. Photoreceptor layer thinning over drusen in eyes with age-related macular degeneration imaged in vivo with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):488–496.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Jhingan M, Singh SR, Samanta A, et al. Drusen ooze: Predictor for progression of dry age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259(9):2687-2694.

- ↑ Bowne J, Daiger SP, Rossiter BJF, Sullivan LS. RetNetTM, Retinal Information Network. https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/ Accessed Jan 11, 2021.

- ↑ Shaw PX, Stiles T, Douglas,C, Ho D, Fan W, Du H, Xiao X. Oxidative stress, innate immunity, and age-related macular degeneration. AIMS Mol Sci. 2016. 3(2),196.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Zarbin MA, Rosenfeld PJ. Pathway-based therapies for age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2010. 30(9)1350-1368.

- ↑ B Gold, JE Merriam, J Zernant, LS Hancox, AJ Taiber, K Gehrs, K Cramer, J Neel, J Bergeron, GR Barile, RT Smith, AMD Genetics Clincal Study Group, GS Hageman, M Dean, R Allikmets. Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006. 38:458-462.

- ↑ JB Maller, JA Fagerness, RC Reynolds, BM Neale, MJ Daly, JM Seddon. Variation in complement factor 3 is associated with risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2007. 39:1200-1201.

- ↑ JRW Yates, T Sepp, BK Matharu, JC Khan, DA Thurlby, H Shahid, DG Clayton, C Hayward, J Morgan, AF Wright, AM Armbrecht, B Dhillon, IJ Deary, E Redmond, AC Bird, AT Moore, The Genetic Factors in AMD Study Group. Complement C3 variant and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357:553-561.

- ↑ GS Hageman, DH Anderson, LV Johnson, LS Hancox, AJ Taiber, LI Hardisty, JL Hageman, HA Stockman, JD Borchardt, KM Gehrs, RJ Smith, G Silvestri, SR Russell, CC Klaver, I Barbazetto, S Chang, LA Yannuzzi, GR Barile, et al. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005. 20:7227-7232.

- ↑ JL Haines, MA Hauser, S Schmidt, WK Scott, LM Olson, P Gallins, KL Spencer, SY Kwan, M Noureddine, JR Gilbert, N Schnetz-Boutaud, A Agarwal, EA Postel, MA Pericak-Vance. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005. 308:419-421.

- ↑ RJ Klein, C Zeiss, EY Chew, J-Y Tsai, RS Sackler, C Haynes, AK Henning, JP SanGiovanni, SM Mane, ST Mayne, MB Bracken, FL Ferris, J Ott, C Barnstable, J Hoh. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005. 308:385-389.

- ↑ AO Edwards, R Ritter III, KJ Abel, A Manning, C Panhuysen, LA Farrer. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005. 308:421-424.

- ↑ Wang Q, Zhao H-S, Li L. Association between complement factor I gene polymorphisms and the risk of age-related macular degeneration: a meta-analysis of literature. Int J of Ophthalmol. 2016; 29(2): 298–305.

- ↑ EM Stone, TA Braun, SR Russell, MH Kuehn, AJ Lotery, PA Moore, CG Eastman, TL Casavant, VC Sheffield. Missense variations in the fibulin 5 gene and age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004. 351:346-353.

- ↑ ML Klein, DW Schultz, A Edwards, TC Matise, K Rust, CB Berselli, K Trzupek, RG Weleber, J Ott, MK Wirtz, TS Acott. Age-related macular degeneration. Clinical features in a large family and linkage to chromosome 1q. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998. 116:1082-1088.

- ↑ DW Schultz, ML Klein, AJ Humpert, CW Luzier, V Persun, M Schain, A Mahan, C Runckel, M Cassera, V Vittal, TM Doyle, TM Martin, RG Weleber, PJ Francis, TS Acott. Analysis of the AMD1 locus: Evidence that a mutation in HEMICENTIN-1 is associated with age-related macular degeneration in a large family. Hum Mol Genet. 2003.12:3315-3123.

- ↑ Z Yang, C Stratton, PJ Francis, ME Kleinman, PL Tan, D Gibbs, Z Tong, H Chen, R Constantine, X Yang, Y Chen, J Zeng, L Davey, X Ma, VS Hau, C Wang, J Harmon, J Buehler, E Pearson, S Patel, Y Kaminoh, S Watkins, L Luo, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 and geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008b. 359:1456-1463.

- ↑ AO Edwards, A Swaroop, JM Seddon. Geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration and TLR3. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:2254-2255.

- ↑ R Allikmets, AA Bergen, M Dean, RH Guymer, GS Hageman, CC Klaver, K Stefansson, BH Weber, Int. Age-Related Macular Degeneration Genetics Consortium. Geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration and TLR3. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:2252-2254.

- ↑ S Zareparsi, M Buraczynska, KEH Branham, S Shah, D Eng, M Li, H Pawar, BM Yashar, SE Moroi, PR Lichter, HR Petty, JE Richards, GR Abecasis, VM Elner, A Swaroop. Toll-like receptor 4 variant D299G is associated with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2005a. 14:1449-1455.

- ↑ AO Edwards, D Chen, BL Fridley, KM James, Y Wu, G Abecasis, A Swaroop, M Othman, K Branham, SK Iyengar, TA Sivakumaran, R Klein, BE Klein, N Tosakulwong. Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008. 49:1652-1659.

- ↑ Z Yang, NJ Camp, H Sun, Z Tong, D Gibbs, DJ Cameron, H Chen, Y Zhao, E Pearson, X Li, J Chien, A DeWan, J Harmon, PS Bernstein, V Shridhar, NA Zabriskie, J Hoh, K Howes, K Zhang. A variant of the HTRA1 gene increases susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2006. 314:992-993.

- ↑ A DeWan, M Liu, S Hartman, SS-M Zhang, DTL Liu, C Zhao, POS Tam, WM Chan, DSC Lam, M Snyder, C Barnstable, CP Pang, J Hoh. HTRA1 promoter polymorphism in wet age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2006. 314:989-992.

- ↑ J Tuo, B Ning, CM Bojanowski, Z-N Lin, RJ Ross, GF Reed, D Shen, X Jiao, M Zhou, EY Chew, FF Kadlubar, C-C Chan. Synergic effect of polymorphisms in ERCC6 5' flanking region and complement factor H on age-related macular degeneration predisposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006.103:9256-9261.

- ↑ Q-L Wang, S Chen, N Esumi, PK Swain, HS Haines, G Peng, BM Melia, I McIntosh, JR Heckenlively, SG Jacobson, EM Stone, A Swaroop, DJ Zack. QRX, a novel homeobox gene, modulates photoreceptor gene expression. Hum Mol Genet. 2004.13:1025-1040 .

- ↑ R Allikmets, NF Shroyer, N Singh, JM Seddon, RA Lewis, PS Bernstein, A Peiffer, NA Zabriskie, Y Li, A Hutchinson, M Dean, JR Lupski, M Leppert. Mutation of the Stargardt disease gene (ABCR) in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 1997. 277:1805-1807.

- ↑ R Allikmets, N Singh, H Sun, NF Shroyer, A Hutchinson, A Chidambaram, B Gerrard, L Baird, D Stauffer, A Peiffer, A Rattner, P Smallwood, Y Li, KL Anderson, A Lewis, J Nathans, M Leppert, M Dean, JR Lupski. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997a. 15:236-246.

- ↑ J Kaplan, S Gerber, D Larget-Piet, J-M Rozet, H Dollfus, J-L Dufier, S Odent, A Postel-Vinay, N Janin, M-L Briard, J Frézal, A Munnich. A gene for Stargardt's disease (fundus flavimaculatus) maps to the short arm of chromosome 1. Nat Genet. 1993. 5:308-311.

- ↑ R Allikmets. Simple and complex ABCR: genetic predisposition to retinal disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2000. 67:793-799.

- ↑ J Jakobsdottir, YP Conley, DE Weeks, TS Mah, RE Ferrell, MB Gorin. Susceptibility genes for age-related maculopathy on chromosome 10q26. Am J Hum Genet. 2005. 77:389-407.

- ↑ A Rivera, SA Fisher, LG Fritsche, CN Keilhauer, P Lichtner, T Meitinger, BHF Weber. Hypothetical LOC387715 is a second major susceptibility gene for age-related macular degeneration contributing independently from complement factor H to disease risk. Hum Mol Genet. 2005. 14:3227-3236.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Thurman JM, Holers VM. The central role of the alternative complement pathway in human disease. J Immunol. 2006 Feb 1;176(3):1305-10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1305. PMID: 16424154.

- ↑ Hageman GS. Age-related macular degeneration. Webvision. http://webvision.med.utah.edu/book/part-xii-cell-biology-of-retinal-degenerations/age-related-macular-degeneration-amd/

- ↑ Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, SanGiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, Hoh J. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005 Apr 15;308(5720):385-9. doi: 10.1126/science.1109557. Epub 2005 Mar 10. PMID: 15761122; PMCID: PMC1512523.

- ↑ Edwards AO, Ritter R 3rd, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005 Apr 15;308(5720):421-4. doi: 10.1126/science.1110189. Epub 2005 Mar 10. PMID: 15761121.

- ↑ Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P, Spencer KL, Kwan SY, Noureddine M, Gilbert JR, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Pericak-Vance MA. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005 Apr 15;308(5720):419-21. doi: 10.1126/science.1110359. Epub 2005 Mar 10. PMID: 15761120.

- ↑ Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Hardisty LI, Hageman JL, Stockman HA, Borchardt JD, Gehrs KM, Smith RJ, Silvestri G, Russell SR, Klaver CC, Barbazetto I, Chang S, Yannuzzi LA, Barile GR, Merriam JC, Smith RT, Olsh AK, Bergeron J, Zernant J, Merriam JE, Gold B, Dean M, Allikmets R. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 May 17;102(20):7227-32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501536102. Epub 2005 May 3. PMID: 15870199; PMCID: PMC1088171.

- ↑ Thurman JM, Holers VM. The central role of the alternative complement pathway in human disease. J Immunol. 2006 Feb 1;176(3):1305-10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1305. PMID: 16424154.

- ↑ Chong EW, Wong TY, Kreis AJ, Simpson JA, Guymer RH. Dietary antioxidants and primary prevention of age related macular degeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007 Oct 13;335(7623):755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39350.500428.47. Epub 2007 Oct 8. PMID: 17923720; PMCID: PMC2018774.

- ↑ Chong EW, Kreis AJ, Wong TY, Simpson JA, Guymer RH. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid and fish intake in the primary prevention of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Jun;126(6):826-33. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.6.826. PMID: 18541848.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 65.4 65.5 65.6 65.7 65.8 65.9 Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Fine SL. Chapter 61. Neovascular (Exudative) Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Retina, Volume II, 4th Edition. Elsevier, Mosby. 2006. Editor: Andrew SP. Schachat.

- ↑ Bressler SB, Do DV, Bressler NM. Age-related macular degeneration: drusen and geographic atrophy. In: Albert DM, Miller JW, Azar DT, Blodi BA, eds. Albert and Jakobiec's Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008: ch. 144.

- ↑ Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY (2012). Age-related macular degeneration. The Lancet. 379:1728-1738.

- ↑ Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Shuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, Hee MR, Flotte T, Gregory K, Puliafito CA, et al. 1991. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 254 (5035):1178-1181.

- ↑ Yannuzzi LA, Wong DW, Sforzolini BS, et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and neovascularized age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999; 117: 1503-1510.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Sarks SH, Sarks JP. Chapter 60. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Nonneovascular Early AMD, Intermediate AMD, and Geographic Atrophy, Volume II, 4th Edition. Elsevier, Mosby. 2006. Editor: Andrew SP. Schachat.

- ↑ Scripsema NK, Hu DN, Rosen RB. Lutein, Zeaxanthin, and meso-Zeaxanthin in the Clinical Management of Eye Disease. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:865179. doi: 10.1155/2015/865179. Epub 2015 Dec 24. PMID: 26819755; PMCID: PMC4706936.

- ↑ National Eye Institute. AREDS/AREDS2 Clinical Trials. National Eye Institute (NEI) https://www.nei.nih.gov/research/clinical-trials/age-related-eye-disease-studies-aredsareds2/about-areds-and-areds2 Accessed Jan 11, 2021.

- ↑ Macular Photocoagulation Study Group (1986). Argon laser photocoagulation for senile macular degeneration. Results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982. 100:912-18.

- ↑ Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for senile macular degeneration. Three-year results from randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982.104:694-701.

- ↑ Meleth AD, Wong WT, Chew EY. Treatment for atrophic macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011 May;22(3):190-3. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834594b0. PMID: 21427574.

- ↑ U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Database, accessed on-line on 05/2012 @ http://clinicaltrials.gov

- ↑ Surgery for Hemorrhagic Choroidal Neovascular Lesions of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Ophthalmic Findings, SST Report No. 13. Submacular Surgery Trials (SST) Research Group*

- ↑ De Pool ME, Campbell JP, Broome SO, Guyton DL. The dragged-fovea diplopia syndrome: clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. Ophthalmology. 2005 Aug;112(8):1455-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.01.054. PMID: 15953644.

- ↑ Hyman LG, Lilienfeld AM, Ferris FL 3rd, Fine SL. Senile macular degeneration: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1983 Aug;118(2):213-27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113629. PMID: 6881127.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Ferris FL 3rd, Fine SL, Hyman L. Age-related macular degeneration and blindness due to neovascular maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984 Nov;102(11):1640-2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040031330019. PMID: 6208888.