Acquired Oculomotor Nerve Palsy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

An acquired oculomotor nerve palsy (OMP) results from damage to the third cranial nerve. It can present in different ways, causing somatic extraocular muscle dysfunction (superior, inferior, and medial recti; inferior oblique; and levator palpebrae superioris) and autonomic dysfunction (pupillary sphincter and ciliary muscles).[1]

Disease Entity

Partial and complete third nerve palsy

Disease

Clinical findings of an acquired third nerve palsy depend on the affected area of the oculomotor nerve pathway. It can be considered a partial or complete palsy. A complete third nerve palsy presents with complete ptosis, with the eye positioned downward and outward with the inability to adduct, infraduct, or supraduct, along with a dilated pupil with sluggish reaction.[2] A partial third nerve palsy may be more common and can present with variable duction limitation of the affected extraocular muscles and with variable degrees of ptosis and/or pupillary dysfunction.[1]

Etiology

There are many etiologies of oculomotor palsy, including a vasculopathic process, trauma, and compression (eg, aneurysm), as well as infiltrative (eg, leukemia) and toxic (eg, chemotherapy) causes.

Risk Factors

Risk factors may coincide with the potential underlying etiologies listed above and can include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, vasculitis, trauma, infection, tumor, or aneurysm.

General Pathology

The manifestations can depend on the location of the lesion. In some cases, the precise site of the lesion is clear, whereas in others, the location of the lesion is speculative.[1]

Pathophysiology

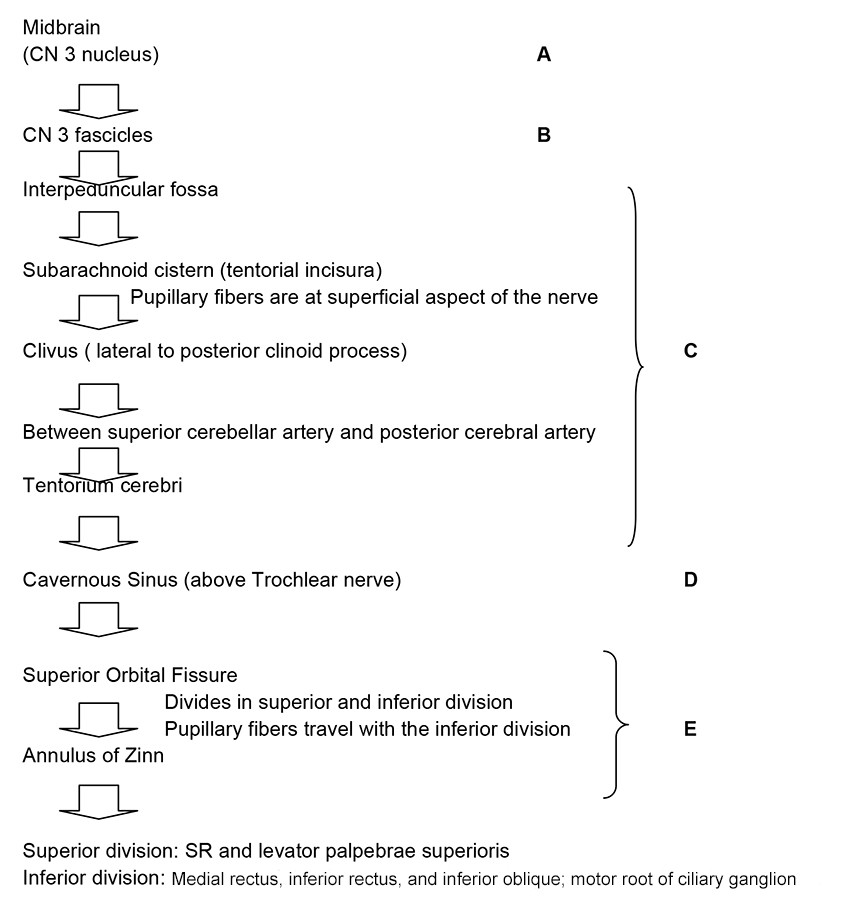

To understand the pathophysiology of the oculomotor nerve palsy, it is essential to know its pathway. The flowchart illustrates the anatomic course of the third cranial nerve (CN III) and is followed by descriptions of clinical manifestations.

Lesions of the Oculomotor Nucleus (Midbrain)

Lesions at this level usually produce bilateral defects, which is explained by the anatomy of the nucleus. It is divided into subnuclei according to the innervated area. Each of the superior recti (SR) muscles are innervated by the contralateral CN III subnucleus; therefore, a nuclear CN III palsy would produce paralysis of the contralateral SR. Both levator palpebrae superioris are innervated by 1 subnucleus (central caudal nucleus); therefore, a central caudal nuclear lesion would produce bilateral ptosis. Patients with damage to the oculomotor nuclear complex need not have ipsilateral pupillary dilation, but when involved, it may indicate dorsal rostral damage.[1] A common cause is ischemia, usually from embolic or thrombotic occlusion of small, dorsal perforating branches of the mesencephalic portion of the basilar artery.[1]

Lesions of the Oculomotor Nerve Fascicles (Leaving the 3rd Nerve Nucleus)

Lesions at this level can produce complete or incomplete palsies. The majority of the time it cannot be differentiated from a lesion outside of the midbrain. When the lesion is adjacent to the CN III nucleus (midbrain), it can produce several manifestations that have been described according to other neurological manifestations. Lesions at the superior cerebellar peduncle (Nothnagel syndrome) present with ipsilateral third nerve palsy and cerebellar ataxia. Lesions at the red nucleus (Benedikt syndrome) are characterized by ipsilateral third nerve palsy and contralateral involuntary movement. Lesions at the red nucleus and superior cerebellar peduncle (Claude syndrome) present with ipsilateral third nerve palsy, contralateral ataxia, asynergy, and tremor. Lesions at the cerebral peduncle (Weber syndrome) produce ipsilateral third nerve palsy and contralateral hemiplegia. It is important to remember that lesions can present a combination of these findings depending on the degree of the insult. In addition, although it is known that CN III separates into superior and inferior rami at the superior orbital fissure, sometimes lesions at the fascicles can produce isolated dysfunction of the superior and inferior division.[1] Causes include ischemic, hemorrhagic, compressive, infiltrative, traumatic, and demyelinating processes.

Lesions in the Subarachnoid Space

This space is defined as the area traveled by the oculomotor nerve between the ventral surfaces of the midbrain to the entrance of the cavernous sinus, also known as the interpeduncular fossa. Oculomotor nerve damage in this area can produce varied presentations. Regarding CN III palsy with a fixed, dilated pupil, it is important to recall that pupillary fibers occupy a peripheral location and receive more collateral blood supply than the main trunk of the nerve.[1] This is why they are susceptible to compression (eg, aneurysm). The most common known etiology is a posterior communicating artery aneurysm. This is a medical emergency. Regarding CN III palsy without pupil involvement, as mentioned above, pupillary fibers occupy a peripheral location and receive more collateral blood supply than the main trunk of the nerve.[1] For this reason, they are less susceptible to ischemia. This is why in most cases patients have diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension, or atherosclerosis and in some cases migraine. Nevertheless, compressive masses or aneurysm can also cause it. On the course to the cavernous sinus, CN III rests on the edge of the tentorium cerebelli. The edge of the uncal portion overlies the tentorium. As a result, in the setting of increased intracranial pressure, this brain section can herniate producing displacement of the midbrain and compressing the ipsilateral oculomotor nerve. This causes ipsilateral ophthalmoplegia and mydriasis. The most common cause of uncal herniation is intracranial hemorrhages.

Lesions Within the Cavernous Sinus and Superior Orbital Fissure

Lesions at these zones can produce an isolated CN III palsy, but they are most commonly associated with other cranial nerve dysfunctions. Differentiating between lesions at the cavernous sinus versus the superior orbital fissure can be challenging, and sometimes the literature describes it as sphenocavernous syndrome. It presents as paresis of the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves with the associated maxillary division of trigeminal nerve, producing pain. This can be caused by primary (direct invasion) or secondary (intracranial/intraorbital lesion compressing these areas) lesions. The most common cause is a tumor (eg, meningiomas). Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is another pathology within the cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure that presents with painful ophthalmoplegia. It is described as an idiopathic granulomatous inflammation. This is a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, tumors, metastasis, or aneurysm must be ruled out with neuroimaging. Although tumors are the most common cause of lesions in this area, vascular processes can also produce damage. Cavernous sinus thrombosis, carotid-cavernous fistulas, syphilis, vasculitis, and/or autoimmune connective tissue diseases (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus) can produce pain typical of cavernous sinus syndrome.[1]

Lesions Within the Orbit

Lesions within the orbit are associated with visual loss, ophthalmoplegia, and proptosis. Third nerve ophthalmoplegia can be associated with trochlear and abducens nerve palsies. It is important to remember that at the orbit the oculomotor nerve divides into the superior and inferior division. This can cause partial oculomotor nerve palsies. The most common etiologies include trauma, masses, inflammation, and/or infiltrative processes.

Primary Prevention

There are many risk factors, but some can be controlled to minimize the risk of acquiring oculomotor nerve palsy. It is encouraged to maintain blood pressure and glycemic control, which are the most common causes of vasculopathic third nerve palsy.

Diagnosis

Acquired oculomotor nerve palsy is a clinical diagnosis.

History

The most common ocular manifestations are diplopia and ptosis. In addition, depending on the affected section of the third cranial nerve track, there can also be other neurologic manifestations such as involuntary movements, hemiplegia, and altered mental status.

Physical Examination

Patients should undergo a complete ophthalmic exam, including visual acuity, ductions and versions, levator function, and pupil reaction to light and to accommodation. In addition, general physical and/or neurological evaluation should be considered.

Signs

The presenting signs depend on the affected area of the third nerve track. In some cases, the precise site of the lesion is clear, whereas in others, the location of the lesion is speculative. It can present in different ways, causing somatic extraocular muscle dysfunction (superior, inferior, and medial recti; inferior oblique; and levator palpebrae superioris) and autonomic dysfunction (pupillary sphincter and ciliary muscles).[2]

Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the location of the lesion. The most common ocular complaint is diplopia secondary to somatic extraocular muscle dysfunction, but pain and ptosis can also be present.

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by physical examination.

Diagnostic Procedures

Acquired oculomotor nerve palsy can be secondary to many etiologies. Nevertheless, neuroimaging is usually done if intracranial pathology is suspected. In a conscious patient presenting with ophthalmoplegia, ptosis, and mydriasis, a compressive etiology, such as an intracranial aneurysm, must be ruled out. If an intracranial aneurysm is suspected, computed tomography angiography (CTA) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI and MRA) should be performed, with a 90% sensitivity in aneurysms at least 3 mm in diameter, although the gold standard is digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

Laboratory Test

If a patient presents with complete oculomotor nerve palsy without pupil involvement, it is most likely related to an ischemic process, but compression and inflammation should also be considered. Evaluation and management will vary according to patient’s systemic illnesses, age, and associated symptoms. Nevertheless, a basic workup is recommended. This may include the following: vital signs (eg, blood pressure), complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP). COVID-19 testing may also be indicated. Central nervous system imaging (MRI or CT) and angiographic studies (MRA, CTA, or catheter angiogram) can be used to rule out acute intracranial pathology, especially if ophthalmoplegia is associated with pain.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

- Myasthenia gravis

- Thyroid eye disease

- Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

- Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia

- Orbital pseudotumor

- Giant cell arteritis

Management

Acquired oculomotor nerve palsy evaluation depends on signs and symptoms, patient age, and systemic diseases. Management depends on the presented scenarios. In a conscious patient with ophthalmoplegia, ptosis, and mydriasis, a compressive etiology, such as an intracranial aneurysm, must be ruled out. On the other hand, if a patient presents with complete oculomotor nerve palsy without pupil involvement, it is most likely related to an ischemic process; however, compression and inflammation should also be considered. The majority of complete or incomplete CN III palsies without pupil involvement are secondary to an ischemic process. These patients see an improvement after the first 4 weeks with full resolution in 12 weeks of the insult.[3] Those patients who are left with a residual deficit can consider prisms or strabismus surgery after 6 months of stability. In these cases, the main goal of strabismus surgery is to provide alignment in primary and reading position.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Miller N, Newman N, eds. Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1998:1194-1223.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 5. Neuro-Ophthalmology. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2010-2011:228-229.

- ↑ Capo H, Warren F, Kupersmith MJ. Evolution of oculomotor nerve palsies. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1992;12(1):21-25.

- Kline LB. Neuro-Ophthalmology Review Manual. 6th ed. Slack Inc; 2007:95-105.

- Kaiser P, Friedman N, Pineda R. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. 2nd ed. Saunders; 2003:39-41.

- Bhatt VR, Naqi M, Bartaula R, et al. T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia presenting with sudden onset right oculomotor nerve palsy with normal neuroradiography and cerebrospinal fluid studies. BMJ Case Rep. 2012:2012:bcr0120125685.

- Appenzeller S, Veilleux M, Clarke A. Third cranial nerve palsy or pseudo 3rd nerve palsy of myasthenia gravis? A challenging diagnosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2009;18(9):836-840.

- Chaudhary N, Davagnanam I, Ansari SA, Pandey A, Thompson BG, Gemmete JJ. Imaging of intracranial aneurysms causing isolated third cranial nerve palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2009;29(3):238-244.

- Trobe JD. Searching for brain aneurysm in third cranial nerve palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2009;29(3):171-173.

- Douedi S, Naser H, Mazahir U, Hamad AI, Sedarous M. Third cranial nerve palsy due to COVID-19 infection. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14280. doi:10.7759/cureus.14280

- Belghmaidi S, Nassih H, Boutgayout S, et al. Third cranial nerve palsy presenting with unilateral diplopia and strabismus in a 24-year-old woman with COVID-19. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e925897. doi:10.12659/AJCR.925897